Patients with late-stage cancer at the back of the mouth or throat that recurs after chemotherapy and radiation treatment are twice as likely to be alive two years later if their cancer is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV).

The data from a new study, led by Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine researchers, was presented at the recent Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancer Symposium in Scottsdale, AZ.

Previous research has found that patients with HPV-positive oropharyngeal (OP) cancers are more likely to survive than those whose cancers are related to smoking or whose origins are unknown, according to the Johns Hopkins researchers.

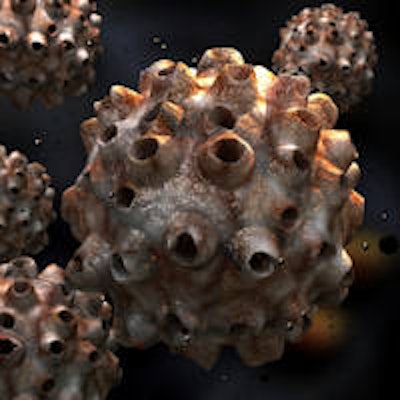

The new study shows that the longer survival pattern holds even if the cancer returns. Oropharyngeal cancers, which once were linked primarily to heavy smoking, are now more likely to be caused by HPV, a virus that is transmitted by oral and other kinds of sex. The rise in HPV-associated OP cancers has been attributed to changes in sexual behaviors, most notably an increase in oral sex partners.

“This study shows us that surgery may have a significant survival benefit, particularly in HPV-positive patients.”

The researchers used data provided by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group on 181 patients with late-stage OP cancer whose HPV status was known and whose cancer had spread after primary treatment. There were 105 HPV-positive patients and 76 HPV-negative ones. Although the median time to recurrence was roughly the same (8.2 months versus 7.3 months, respectively), some 55% of those with HPV-positive cancer were alive two years after recurrence, while only 28% of those with HPV-negative cancers were still alive.

The researchers also found that those whose cancers could be treated with surgery after recurrence -- regardless of HPV status -- were 52% less likely to die than those who did not have surgery. Surgery has typically been done in limited cases, as doctors and patients weigh the risks of surgery against higher morbidity associated with recurrent disease, they noted.

"Historically, if you had a recurrence, you might as well get your affairs in order, because survival rates were so dismal. It was hard to say, 'Yes, you should go through surgery,' " said study lead Carole Fakhry, MD, MPH, an assistant professor in the department of otolaryngology -- head and neck surgery at Johns Hopkins. "But this study shows us that surgery may have a significant survival benefit, particularly in HPV-positive patients."

While it remains unclear why patients with HPV-positive tumors have better outcomes than those with HPV-negative tumors, researchers speculate it may be due to biologic and immunologic properties that render HPV-positive cancers inherently less malignant or better able to respond to radiation or chemotherapy treatment.

"Until this study, we thought that once these cancers came back, patients did equally poorly regardless of whether their disease was linked to HPV," Dr. Fakhry said. "Now we know that once they recur, HPV status still matters. They still do better."

Roughly 37,000 people in the U.S. will be diagnosed with cancer of the oral cavity and oropharynx in 2014, according to the American Cancer Society. While the incidence of head and neck cancer has been declining over the past 30 years, the rate of HPV-positive OP cancer is rapidly rising. Today, nearly 70% of OP cancers are HPV-positive.

Researchers from the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Statistical Center in Philadelphia; CHUM Hospital Notre Dame in Montreal; MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston; Stanford University Medical Center in Stanford, CA; and Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, OH, also contributed to the study. The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health's National Cancer Institute and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The 2014 Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancer Symposium was sponsored by the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the American Head & Neck Society (AHNS).