No one doubts the advantages that cone-beam CT (CBCT) can bring to dental diagnostics. But the adoption of this technology by general dentists also raises some medicolegal concerns, according to Bernard Friedland, BChD, M.Sc., J.D., head of the division of oral and maxillofacial radiology at the Harvard School of Dental Medicine.

Writing in Seminars in Orthodontics (March 2009, Vol. 15:1, pp. 77-84), Dr. Friedland notes that with the advent of more affordable cone-beam CT systems and dental-specific CBCT software, a growing number of general dentists are considering purchasing CBCT scanners.

“Cone-beam CT holds great promise for both patients and dentists, but it comes with potential pitfalls.”

— Bernard Friedland, BChD, M.Sc., J.D.,

Harvard School of Dental Medicine

But they should consider some key issues -- including radiation exposure, image interpretation, and ownership -- before investing in this equipment because the potential liabilities could put them at legal risk, Dr. Friedland emphasized in an interview with DrBicuspid.com.

When it comes to image acquisition, for example, one issue is which areas of the jaw and head or neck should be included in a study, and what this means in terms of radiation exposure for the patient.

"Assume one takes a CBCT scan of the fully edentulous maxilla for purposes of evaluating the feasibility of placing implants," he wrote in Seminars. "Does the image provide sufficient coverage if the beam is collimated (in the vertical) to include just the alveolar bone and only 2 to 3 mm superior to the sinus floor? Or is it necessary to include more of or perhaps even the entire sinus?"

It is also possible to collimate too narrowly, he added, thus excluding structures that actually should be included.

"Some users will take a whole head scan even if they only want to look at one area," Dr. Friedland told DrBicuspid.com. "But you don't need to take a whole head image if you just want to look at the mandible. It's like going into a hospital with a finger problem and the radiologist takes an image all the way up to your shoulder. You don't always need the best resolution. You want to choose the resolution that meets your need."

Another issue is interpretation. As with any diagnostic image, a dentist assumes liability for the interpretation of that image. "A CT is no different than any other images -- a dentist cannot read only part of a panoramic film or only part of a lateral cephalogram," Dr. Friedland noted.

But many dentists are unfamiliar with the radiographic 3D anatomy of the head and neck and don't have the pathology expertise to interpret the images, he added. "And that is the number one concern: interpretation of images," he said.

|

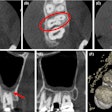

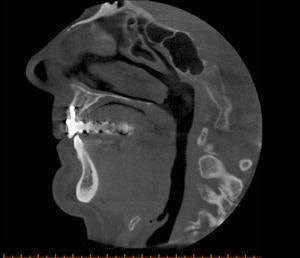

| Cone-beam CT images from two different patients. The top CT image was taken to evaluate the mandible for implant purposes; the other was taken to evaluate the maxilla for implant purposes. The images show how much more of the head was exposed than needed to be. Also, one CT was done at 0.25 voxels, which is more resolution than is needed for a typical implant CT. Images courtesy of Dr. Bernard Friedland. |

|

The issue then becomes one of deciding whether to refer the image interpretation out and, in some cases, whether it is OK to cross state lines in doing so -- that is, whether a radiologist in another state is legally entitled to read and interpret your images, CT or otherwise, even though they are not licensed in your state.

"While modern technology has made the referral of the reading of images a simple matter, the law has not caught up with these changes," Dr. Friedland wrote. "On the technical side, it is a simple matter for a dentist to have the images, which are all digital, read remotely by a radiologist. ... Unfortunately, dental licensing laws remain firmly entrenched in centuries past."

Jackie Raulerson, media relations manager for Dexis, Gendex Dental Systems, and Imaging Sciences International, contends that cone-beam CT companies provide adequate training and support to enable general dentists to take and interpret 3D images.

"We provide a day and a half of onsite technical training by certified instructors, most of whom have a radiology background, on how to use the machine," she said. "They explain what cone beam is so the whole staff will understand it, and then they walk everyone through how it works."

This training is included in the purchase price, but Gendex -- which sells the GXCB-500 system – and Imaging Sciences -- which sells the iCAT system -- also offer additional local, regional, and national courses and sponsor the iCAT Imaging Institute.

"Beyond learning how to use the machine and the software, we strongly suggest that our owners seek more clinical training to better serve their patients," she said. "But I do believe 3D imaging will become the standard of care in the near future."

Beyond image interpretation

From a legal perspective, however, the issues go well beyond image interpretation, Dr. Friedland noted. For example, while some states allow nondentists (such as x-ray laboratories) to own and operate dental cone-beam CT systems, others have laws that make it difficult for fully licensed dentists or radiologists to acquire a cone-beam CT system.

For example, Michigan requires a "certificate of need" (CON) to be in place before a dentist practicing in the state can purchase a cone-beam CT system. CONs, which are common in the medical community but less so in dentistry, are designed to restrict unnecessary increases in healthcare costs and limit unnecessary health services and facilities based on geographic, demographic, and economic considerations.

It's a law Dr. Friedland wishes other states would adopt as well.

"What we charge for the most basic CT (at his practice in Boston) is $250," he said. "But that same procedure 45 minutes outside of Boston -- where there are two dentists near each other who both have CBCT machines -- will cost $375 to $400 because they have to justify the cost of the machines. This is why there are CONs. It is a matter of economics."

But Raulerson, who is based in Michigan, said CONs are "extremely limiting."

"There are many dentists here who place implants, and they would like to have their own cone-beam CT systems," she said. "And for implants, 3D makes a huge difference in safety. But the CON stands in the way. I know it is trying to protect the patient, but at what cost?"

Another consideration is the Stark law, which can come into play when a dentist opts to jointly purchase a cone-beam CT system with a physician. This law prohibits physicians from making referrals for a designated health service, payable by Medicare of Medicaid, to any entity with which the physician has a financial relationship. Designated health services include the taking and interpretation of a CT scan in a physician's office or freestanding facility, according to Dr. Friedland.

"If a dentist were to enter into a business relationship with a physician, almost all of whom accept Medicare and/or Medicaid payments, the dentist, even though he does not himself accept such payments, might find himself under investigation," he wrote in Seminars.

There are also related antikickback laws. Dr. Friedland recommends that any dentist considering purchasing a cone-beam CT system in conjunction with a physician first consult an attorney who specializes in these laws.

"Cone-beam CT holds great promise for both patients and dentists, but it comes with potential pitfalls," he concluded in his Seminars article. "With careful planning and the use of appropriately qualified individuals to aid in interpretation, dentists can enhance their practice and best serve the interest of their patients."

"That says it all," Raulerson agreed. "It is all about better patient care."

Copyright © 2009 DrBicuspid.com