Pick, pick, pick! Probing for caries with a dental explorer is a time-honored practice. So research that challenges this fundamental procedure ignites a fevered debate. Now a recent study in the January issue of Caries Research has added fuel to the flame.

Researchers from the University of Munich looked at probed teeth with a scanning electron microscope and found scratches. How bad? So bad that they think all probing should stop. "Dental probing should be considered as an inappropriate procedure and should be replaced by a meticulous visual inspection," they wrote.

That’s asking a lot since, by most estimates, the vast majority of dentists still use probes to find carious lesions.

The practice of probing -- and apprehension about the practice -- goes back at least 50 years, according to George Stookey, PhD, a distinguished professor emeritus of dentistry at Indiana University who is developing an electronic device for detecting caries. In 1969, researchers peering through conventional microscopes could also see marks left by probing. In 1995, microradiography also showed scratch marks.

This led some researchers to speculate that the probe might worsen incipient lesions that might otherwise heal if properly cleaned and treated with fluoride. "If you probe the surface and you break the surface layer, you are eliminating the possibility of remineralization," said Dr. Stookey to DrBicuspid.com.

But does such minute damage really lead to cavities?

The Munich team hoped their scanning electron microscope could provide answers. To compare probed teeth versus unprobed ones, the team recruited 18 patients aged 17 to 26 whose wisdom teeth were set for extraction. The investigators visually examined the teeth and eliminated from the study any with frank lesions or microcavities. Teeth with white or brown spots on the occlusal surfaces were considered as having initial carious lesions. The rest they categorized as sound.

This left the investigators with 30 teeth in two groups: "sound" and "initial carious." Next, they subdivided these teeth into three equal groups according to the type of probing they would receive: 1) probing of sound pits and fissures, 2) probing of initial carious pits and fissures, and 3) no probing. After the probing, the investigators extracted the teeth and examined them using a Philips Scanning Electron Microscope 515.

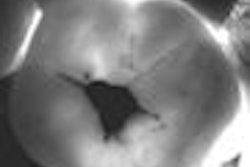

It wasn’t a pretty sight. The explorer scored the surface of all the teeth in the "initial lesion" group. Small chunks of enamel were broken in some, and in others the enamel appeared compressed. Some occlusal pits hollowed by the tip of the explorer yawned as wide as a millimeter.

By contrast, among the 10 "sound" teeth, only two surfaces were scratched. Likewise the unprobed teeth showed no signs of such scratching.

It was enough to convince the investigators that "probing can convert an initial carious lesion into a cavity" and that the hunt and pick approach should be avoided.

So what's the alternative? Begin by looking closely at the color and location of possible lesions, Dr. Stookey advises. The explorer can still serve a purpose, he said, as long as you don't press too hard. Instead of forcing the tip into possible lesions to see if it sticks, he recommends stroking as lightly as possible against questionable spots to detect roughness.

Not everyone believes this gentler approach can work. James C. Hamilton, DDS, a clinical associate professor at the University of Michigan told DrBicuspid.com that he's not convinced traditional probing worsens tooth decay. "I agree there is damage to the tooth," he said. "But there is no evidence that this microscopic damage causes any trouble to anybody."

To know for certain that probing causes long-term damage, researchers agree you would have to leave the teeth inside the patients’ mouths and follow their progress over several years to see whether probed teeth fare any worse than unprobed teeth. That's an expensive, long-term study that no one has been willing to fund so far.

Dr. Hamilton’s own research team has come as close as anyone, he said, with a study published in the December 2002 issue of The Journal of the American Dental Association. That study assessed whether patients would lose more healthy tooth matter if their dentists restored incipient lesions or waited until the lesions became frank cavities.

The study concluded that early treatment held no advantages for the patient, and, since the investigators probed a lot in the control population, the probing didn’t hurt anything.

On the other hand, a 1991 Caries Research study found that probing was no more accurate in diagnosing caries than just closely looking at patients’ teeth.

Dr. Hamilton’s swift reply: dentists in the 1991 study weren’t using proper probing technique. And so it goes.

Dr. Hamilton and Dr. Stookey agree on one thing: the controversy isn’t likely to die any time soon.

Sources:

Caries Research, Jan. 2007, Vol. 41 No. 1, pp. 43-48

Journal of the American Dental Association, Nov. 2005, Vol 136, pp. 1526-1532