It's not often a dentist gets to raise something from the dead. But the resurrection -- technically known as revitalization -- of nonvital teeth is becoming a possibility thanks to regenerative endodontic techniques.

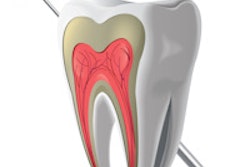

Nonvital infected teeth have long been treated with root canal therapy and apexification, or doomed to extraction. Although largely successful, current treatments fail to re-establish healthy pulp tissue in these teeth.

But what if the nonvital tooth could be made vital once again? That's the hope offered by regenerative endodontics, an emerging field focused on replacing traumatized and diseased pulp with functional pulp tissue. Various regenerative techniques -- including stem cell therapy, pulp implants, and gene therapy -- are currently being studied. But as of now, one stands out as perhaps the most practical: root canal revascularization.

With this technique, dentists simply puncture the periapical tissue with a sterile needle to create a blood clot on which the pulp grows back.

"Revascularization simulates natural maturation of the root in immature infected teeth, which have incompletely developed roots," explained Naseem Shah, M.D.S., a professor and head of conservative dentistry and endodontics at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi, India.

Revascularization has a dual purpose, added Francisco Banchs, D.D.S., D.M.D., M.Sc., who published a case report of a successful revascularization treatment in the Journal of Endodontics (April 2004, Vol. 30:4, pp. 196-200). One purpose is to provide the patient with natural regenerated tissue on the inside of the tooth instead of an artificial filling. The other is to address the incomplete development of the immature tooth.

"This regenerated tissue will allow further development until full mature formation of the tooth, giving back the strength and functionality of the tooth for years to come," said Dr Banchs, who is currently in private practice in Saratoga Springs, NY.

How it works

The exact mechanism behind revascularization is unclear. It's possible that dental pulp stem cells and vital pulp cells remaining in the apical end of the root canal might be populating onto the new matrix, Dr. Shah said. Stem cells from the periodontal ligament and apical papilla and growth factors from the blood clot might also play a role.

In one of the first clinical trials, published last year in the Journal of Endodontics (August 2008, Vol. 34:8, pp. 919-925), Dr. Shah and her colleagues disinfected the root canal using 3% hydrogen peroxide and 2.5% sodium hypochlorite irrigants.

They used minimal filing and immediately sealed the coronal access with formocresol in the canal space between visits (an antibiotic mix of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and minocycline was employed by Dr. Banchs in a previous case report but was not used in this study). The total number of visits depended on the degree of infection, which could take up to three visits to control, Dr. Shah noted.

Once the root canal was disinfected, revascularization required only a single sitting. The researchers punctured the periapical tissue with a sterile needle. Then they held a cotton pellet in the pulp chamber for several minutes to form a clot. Finally, they sealed the access using glass ionomer cement.

Case follow-up ranged from six months to three and a half years. "Overall, the treatment outcome was very consistent," said Dr. Shah, who observed complete resolution of clinical symptoms and healing of periapical lesions in 78% of the cases. Eight of 14 cases demonstrated thickening of lateral dentinal walls and root length increased in 10 cases.

So should dentists add root canal revascularization to their arsenal?

Dr. Banchs takes a cautionary approach, considering the lack of a specific case selection process. "These cases are very technique-sensitive, and case selection is key for a successful outcome," he said.

Dr. Shah believes the procedure is time- and cost-effective and a good alternative to traditional treatment of immature infected teeth, which are prone to fracture after treatment. However, additional revascularization studies with a larger number of cases and longer follow-up are necessary, she added.

Looking ahead

Dr. Banchs advises against using the technique in mature teeth, since the root tip would be destroyed. Hope for mature teeth depends on more sophisticated techniques, according to Peter Murray, Ph.D., an associate professor in the department of endodontics at Nova Southeastern University. Among the approaches being considered:

Dentists may regenerate a replacement pulp by injecting postnatal stem cells into disinfected root canal system after the apex has been opened.

Dentists could transplant tissue-engineered scaffolds into the root canal system with or without stem cells. The seeding of dental pulp stem cells onto scaffolds to create a synthetic dental pulp constructs, was first performed on extracted teeth by Eric Gotlieb, D.D.S., and colleagues last year (Journal of the American Dental Association, April 2008, Vol.139:4, pp. 457-465).

There is also potential use of platelet-rich plasma, noted Murray, which involves collecting blood from patients and centrifuging it to create a natural "scaffold glue" that can be used to create scaffolds to fill the root canal.

Further down the road, researchers imagine delivering scaffolds via injection using hydrogels. In an even more high-tech scenario, they might try 3D cell printing, using an ink-jet-like device dispensing layers of cells in a hydrogel, which is surgically implanted.

Gene therapy, based on delivering mineralizing genes into pulp tissue to induce tissue mineralization, has high health risk hazards and will not likely be employed in endodontics in the near future, Murray said.

"The revascularization technique is only part of the story," Dr. Banchs said. "The critical aspect is to have a biological understanding of what we're trying to attain and why, keeping always the benefit of the patient a top priority."

Copyright © 2009 DrBicuspid.com