The fight against the pandemic hinges on more than the efficacy of upcoming COVID-19 vaccines. The path to victory depends on how the public perceives the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines, according to a recent discussion by a panel of physicians and scientists.

At a time when people's trust in the U.S. government and its leading health agencies and organizations continues to dwindle, dentists, hygienists, doctors, and other healthcare professionals need to reach their patients and explain the benefits of vaccination. Public buy-in can grow with results and recommendations from these people whom patients know and trust.

"Once these vaccines are approved, we want to make sure that there is public trust in these vaccines, because nothing will be effective if the people don't take it," said Dr. Shobha Swaminathan, an associate professor at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, at the briefing held on October 29 and organized by Newswise.

Follow the science

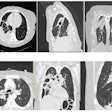

Studies of SARS-CoV-2 infection have shown that patients with more severe cases of COVID-19 have a greater antibody response than those with mild cases of the disease. This is "reflective of an arms race between the virus and the immune system," said Sean Diehl, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine.

The immune system has mechanisms in place to detect replicating viruses in the early stages of infection, with more viral material being made as the virus spreads. As the system gets the virus under control, the neutralizing antibodies remain in the body, which explains why patients with more severe cases of infection have more antibodies.

As an example of the durability of antibodies, Diehl explained that individuals who had the original SARS-CoV virus from 2003 were recently rebled, 17 years after exposure, and they still retained strong neutralizing antibody responses and antigen-specific memory T-cell responses. As the viral characteristics of SARS-CoV are in the same antigenic family as SARS-CoV-2, this bodes well for long-term protection from antibodies against COVID-19, Diehl said.

Although these antibody responses are from natural infection and not inoculation, many vaccine manufacturers plan to follow their trial volunteers for up to 26 months to examine the durability of the vaccine antibody response.

Many scientists believe that a rise in antibodies may confer some level of protection if an individual is reinfected with SARS-CoV-2. However, Dr. Robert Salata, a professor of medicine, epidemiology, and international health at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, said that "given that 47 million people around the world have been infected, and there are only a handful of scientifically documented reinfection cases, that [reinfection is] still few and far between at this point in time."

Many of the COVID-19 vaccines being developed are aiming for a minimum efficacy rate of 50% to 60%, meaning that a vaccine would protect against infection in 50 to 60 out of 100 recipients who are exposed to the virus. To achieve herd immunity, an efficacy rate of at least 70% must be achieved, if all individuals receive a vaccine.

One vaccine won't cut it

Vaccines alone will not end the COVID-19 pandemic, but they will be one tool that decreases the circulation of SARS-CoV-2 in the population, and vaccination efforts should be combined with all other public health measures, said Dr. Stephen Spector, a professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

"[A single vaccine] will add to the amount of antibody responses and T-cell responses in the general population," Salata said. "And hopefully we'll get to that level of herd immunity that was already mentioned, but it will take a while, and we will not be able to move away from these strict public health measures in the interim."

For instance, Pfizer has committed to providing the U.S. with 100 million doses of its vaccine, but given that the vaccine requires two separate injections, this will only cover 50 million people. With 325 million to 330 million individuals, Salata said it will take multiple vaccine platforms due to "sheer numbers and distribution issues."

"We are going to need multiple options -- bottom line," Salata advised.

As a silver lining, all the public health measures currently in place to reduce COVID-19 transmission -- such as social distancing and mask wearing -- are probably also very effective against other respiratory viruses, including influenza and respiratory syncytial virus.

Pandemic fatigue and craving normalcy

The behavioral aspects of human nature play as much a role in the efficacy of vaccines as the biological aspects, according to Perry Halkitis, PhD, MPH, dean of the Rutgers School of Public Health. He explained that people have a difficult time maintaining behaviors, and a lack of personal responsibility and altruism makes it easy for individuals to think that they are immune without considering that other people may be more susceptible to the disease.

If this is true and these individuals don't buy into the idea of getting the vaccine, then they may continue to spread the disease and prevent vaccine and public health efforts from being effective.

Regarding recent pauses in the AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson vaccine trials, these companies have moved ahead after resolving concerns about the safety and potential side effects of their vaccine candidates, according to Dr. Edward Jones-Lopez, an assistant professor at Keck Medicine of the University of Southern California.

"This is really about sending a very important message to the public" that the system is functioning as intended and safety standards are being meticulously maintained, he said.

The future of COVID-19 vaccines

Many of the vaccines currently being developed only use one part of the virus; they are, therefore, an important stopgap measure, but they will not provide full protection as with live-attenuated vaccines. Previous outbreaks have provided guidance for better responses to future outbreaks, as well as an understanding of how to move new technologies through regulatory pipelines, according to Diehl.

As time goes on, "we will learn more about how the virus behaves and be able to design better and better vaccines," he said.