Rare and noncancerous but aggressive vascular maxillofacial lesions, which can damage bones and nerves if untreated, were detected as incidental findings on two patients' dental x-rays. The cases were published on February 12 in the Australian Dental Journal.

Asymptomatic juvenile angiofibroma was detected on the radiographs of a 15-year-old boy and 26-year-old man who underwent imaging in preparation for orthodontic treatment. Identifying the lesions facilitated early diagnosis and treatment, the authors wrote.

"This highlights the importance of accurate interpretation of imaging commonly performed in dentistry, including the thorough evaluation of structures beyond the regions of interest," wrote the group, led by Dr. Sadaf Rizwan of the University of Queensland School of Dentistry in Australia.

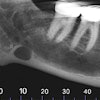

Case 1: 15-year-old boy

Prior to orthodontic treatment, the teen was sent to a private radiology practice to get x-rays. He had no symptoms and an unremarkable medical history.

Upon reviewing the teen's x-ray, the oral and maxillofacial radiologist identified anterior displacement of the rear wall of his left maxillary sinus and a widening of the left pterygomaxillary fissure.

The patient underwent computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) exams. The images showed a lobulated lesion centered at the widened left pterygomaxillary fissure and extending medially into the patient's posterior nasal space, pushing the nasal septum to the right.

The lesion also changed the contour of his nasopharynx and moved into the sphenoid sinus. Anterolaterally, the tumor spread into the maxillary antrum and masticator space deep to the temporalis muscle, the authors wrote.

The radiologist observed no internal calcifications on the CT scan. The boy was diagnosed with juvenile angiofibroma and referred to a hospital for treatment.

The patient underwent angiographic embolization, and the lesion was removed surgically. He recovered without complications.

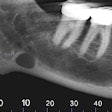

Case 2: 26-year-old man

Prior to orthodontic treatment, the man was sent to a private radiology practice to undergo a lateral cephalogram. He had no symptoms and an unremarkable medical history.

After reviewing the images, an oral and maxillofacial radiologist identified anterior bowing of the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, as well as a large soft-tissue mass at the posterior-superior nasopharynx. These were strong indicators of a lesion, including juvenile angiofibroma, and prompted the radiologist to order more imaging.

CT and MRI showed a contrast-enhancing mass in the man's left posterior nasal area. The mass extensively widened the sphenopalatine foramen and pterygopalatine fossa with scalloping of the maxilla and pterygoid bones extending laterally to the pterygomaxillary fissure.

The lesion was isointense with muscle on T1-weighted MRI, and it insinuated around the ventral lateral pterygoid muscle insertion. Medially, there was ipsilateral septal and posterior turbinate displacement, and superiorly, the lesion eroded and bulged into the sphenoid sinus.

Clinicians suspected the lesion had been there for some time. The man was diagnosed with juvenile angiofibroma and referred to an ear, nose, and throat physician for treatment.

Diagnosed for millennia

The oldest case of juvenile angiofibroma dates to the 5th century BC. Written records indicate that Hippocrates removed a juvenile angiofibroma lesion by performing a longitudinal splitting of a patient's nasal ridge. Though this lesion type has long been known to the medical profession, the reported incidence rate is between 0.05% and 0.5% of all head and neck lesions, according to the authors.

Found mostly in young men, juvenile angiofibroma is a benign tumor composed of connective tissue and blood vessels. The tumors form in the back of the nose, but they can spread to the sinuses, the upper part of the throat, and the bone around the eyes. Rarely, a tumor will spread to the brain. Eventually, these growths can damage nerves and bones.

Current opinion is that genetics, hormones, and HPV infection may play a part in the development of juvenile angiofibroma. Many people are asymptomatic, but potential symptoms include nosebleeds, hearing loss, double vision, and trouble breathing through the nose. The lesions can be difficult to treat based on their size and location, according to the authors.

"Early presymptomatic identification of angiofibroma facilitates early management and limits potential life-threatening complications," Rizwan and colleagues concluded.