Patients who grind their teeth may be significantly more likely to show bone apposition on panoramic dental x-rays, indicating another possible way to diagnose bruxism. The study was published on October 18 in BMC Oral Health.

An appreciable number of patients with bruxism in the study had bony changes in the condylar area and the mandibular angle. This is believed to be the first study to examine morphological changes among those with and without bruxism, the authors wrote.

"In addition to self-report and clinical examination, radiologically diagnosed bone apposition may serve as an additional diagnostic indicator of bruxism," wrote the group, co-led by Dr. Jens Christoph Turp and Michelle Simonek from the University Center for Dental Medicine Basel at the University of Basel in Switzerland.

Bruxism is a common condition in adults, with an estimated prevalence of about 30% in those who are awake and 15% in those who are asleep. Sustained bruxism increases a person's risk of tooth wear, anterior disk displacement, and pain in the masticatory muscles or temporomandibular joints.

Currently, clinicians assess bruxism using self-reports from patients, clinical exams, and instrumental strategies, like electromyographic recordings. Though together they help form a valid bruxism diagnosis, instrumental diagnostic procedures are less frequently available. Further, they require more time and can be costly. Due to these limitations, having alternative methods to diagnose bruxism would be helpful.

To determine whether there was a correlation between bruxism and bony changes in the jaw, the researchers examined 200 panoramic x-rays from patients. Half of the images were from adults who were diagnosed with bruxism, and the other half were from children between the ages of 12 and 18. Children were used as a control group because it was expected that their mouths would show no signs of bone apposition, according to the authors.

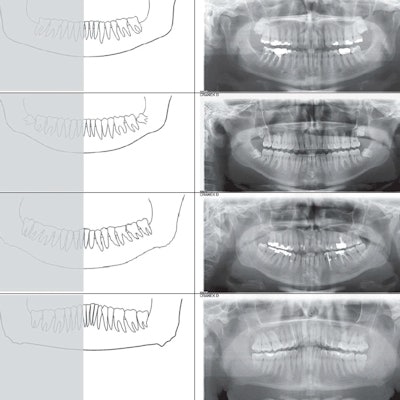

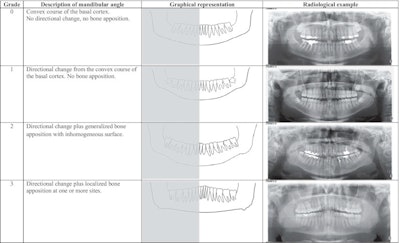

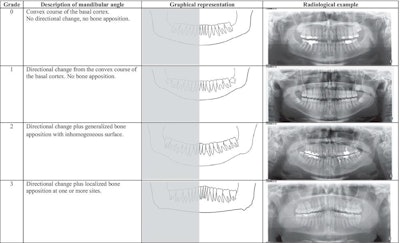

Bony changes were found in 95 mandibular angles of 59 adults with bruxism. Though the degrees of apposition varied, almost two-thirds of these patients had bilateral bony changes. Except for two mandibular angles viewed, each bone apposition was partnered with a directional change of the corresponding lower jaw angle. As expected, no bony changes were seen on the children's x-rays, the authors wrote.

Grade, description, graphical representation, and radiological example of bone apposition at the mandibular angle. Image courtesy of Turp et al. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Due to the summation effect of panoramic x-rays, the precise location of the appositions could not be defined. Though a limitation of the findings, the lack of location of the bony changes was irrelevant for this study, they wrote.

When dental x-rays show bony changes at patients' mandibular angles, the changes should be interpreted as a functional adaptation to the long-term increased loads that occur when the jaw-closing muscles contract due bruxism, the authors wrote.

"Radiologically diagnosed bone apposition may serve as an indication or confirmation of bruxism," they wrote.