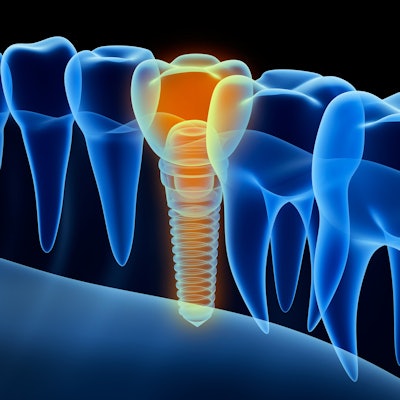

A patient's dental implant failed twice due to a cystic lining growing around it, in a rare case that was detected without signs of periapical radiolucency on an x-ray, according to a case report.

Initially, a clinical exam and scans mistakenly showed that the failure was due to peri-implantitis-related bone loss. The case highlights the importance of having tissue examined for histopathology, according to the report published online July 3 in the Journal of Oral Biology and Craniofacial Research.

"This represents one of the first [publications] of an evident peri-implant cystic lining in a case exhibiting no radiographic evidence of the same," wrote the authors, led by Yazad Gandhi, MD, a consultant maxillofacial surgeon at Saifee Hospital in Mumbai, India.

Successes and failures

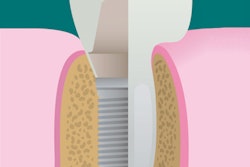

Though dental implants have high rates for success, failures occur that require their immediate removal. The diameter of fixtures, the type of bone, and the length of fixtures influence their success, as well as biological and biomechanical factors that have a cumulative effect on the final amount of bone loss. Clinicians must understand these factors and their relative contributions and interactions to ensure the long-term success of implants. Though it is considered normal to see a settling of crestal tissues in a patient's mouth after dental implants, clinicians need to understand the subtle difference between this nonpathologic cause of reduction in bone height and that which is due to inflammatory causes, which this case sheds light on.

A 45-year-old healthy man

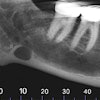

The patient presented with a missing molar. Clinical and x-ray exams showed a vertical fracture in his mandibular left first molar with a history of endodontic treatment. The treatment plan included extracting the roots, grafting the socket, and intervening at the second stage to place the implant. The patient underwent local anesthesia and the roots were extracted and the socket was debrided. Autogenous bone taken from the mandibular retromolar region was used to graft the socket and an absorbable collagen plug was used to seal it, according to the authors.

A tapered internal implant was placed as a submerged unit three months later. After three months, the implant was uncovered, implant stability quotient (ISQ) values of 68 were measured, and a hybrid cement screw-retained porcelain fused to metal crown was inserted and torqued to 35 Ncm. One week before his routine four-month follow-up, the patient reported discomfort when chewing. A clinical exam revealed that the screw-retained unit showed second-degree mobility in the buccal and lingual aspects of the tooth, as well as a peri-implant probing depth of about 7 mm, according to the report.

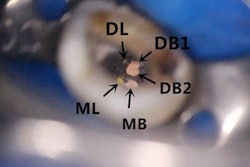

The screw-cement crown-abutment complex was disconnected from the implant, then it was retrieved. Damaged tissue was removed from the osseous defect and a mixture of autograft and allograft was placed and covered with a resorbable collagen membrane. Meanwhile, the mandibular left second premolar was tender upon touch and caused frequent bouts of moderate to severe pain. An endodontist was consulted, but the treatment presented was not amenable to any conservative restorative procedure.

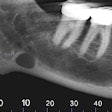

Four months later, a tapered internal implant was submerged and left for three months. The implant was uncovered, ISQ levels of 77 were measured, and the implant was loaded with the same type of prosthesis used the first time. Six weeks after the patient received the implant, he was found to have 2° mobility in the crown. X-rays revealed unzipping of the bone around the implant, so the screw-retained unit was removed and replaced with a gingival former. A cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan showed peri-implant loss of bone down to the junction of middle and apical third, according to the authors.

A trephine was used to remove the implant along with peri-implant granulation tissue and some surrounding bone so the pathology of the tissue could be examined. This exam revealed that a cystic lining grew around the implant. The failure was diagnosed as a cystic lumen lined by nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium covering chronically inflamed connective tissue.

Free of any other risk factors, a new screw-retained unit was implanted and checked thoroughly. The patient had adequate keratinized soft tissue both buccally and lingually following the procedure, and at his four-month checkup, a CBCT scan revealed satisfactory bone fill, the authors wrote.

A thorough exam

According to the authors, clinicians should explore all possibilities when dental implants fail.

"Had it not been for the histopathologic examination, the cause for this repetitive failure would have remained in doubt," they wrote.