Painful stones don't just happen in the kidneys and gallbladder. They can also cause problems in the salivary glands, prompting invasive surgery through the face or neck that can lead to nerve damage, cosmetic scarring, and even gland removal.

Luckily, European advances in endoscopic diagnosis and surgery have made possible less invasive treatments of salivary stones (sialoliths), and these techniques are increasingly making their way to the U.S.

"Now patients just have more options," said M. Boyd Gillespie, M.D., M.Sc., an associate professor of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery at the Medical University of South Carolina. "There are options other than gland removal."

Causes unclear

What prompts the development of these stones isn't entirely clear, but they're the most common cause of salivary gland obstruction, believed to affect about 1.2% of people in the course of their lives. Generally composed of calcium phosphate and carbon, the stones have a mean size of about 6 mm to 9 mm, with sizes rarely larger than 1.5 cm. A giant sialolith -- 3.5 cm or more -- is very rare.

|

| Large sialolith, measuring more than 2 cm across. All images courtesy of Dr. M. Boyd Gillespie, Medical University of South Carolina. |

Stones and other salivary gland obstructions tend to be noticed and diagnosed in relation to mealtimes. Because the salivary flow is obstructed, the salivary gland swells and can become painful with sour foods such as pickles, but also even at the thought of food. For about 30% of patients, this swelling is painless. The stagnant saliva backed up behind the obstruction can cause infections, leading to fevers, purulent drainage, abscesses large enough to threaten the patient's airway, and even skin fistulas secondary to suppurative infections.

More than 60% of sialoliths occur in the submandibular gland and its associated duct, possibly because it has more viscous saliva with a higher mineral content and a longer duct. About 10% are in the parotid glands, while the remaining occur in the sublingual or minor salivary glands.

Although the causes of these stones are unknown, dry mouth appears to be a risk factor. Because of this, patients taking medications that dry the mouth, smokers, people who have had radioiodine because of thyroid cancer, and people with autoimmune diseases that affect salivary flow such as Sjögren's syndrome appear to have a higher incidence.

As with most medical problems, nonsurgical treatment methods should be tried first. These include increasing liquids, massaging the glands, warm compresses, and sucking on sour candies to stimulate salivary flow. Dentists have had some success with bimanual palpation of the gland to "milk out" small stones (European Journal of Dentistry, April 2009, Vol. 3:2, pp. 135-139). Some patients may also need antibiotics.

Endoscopic techniques

If these methods prove unsuccessful, recent advances in endoscopy can help to both diagnose and treat the problem.

At least 20% of submandibular stones and 50% of parotid stones are not opaque on x-rays, making ultrasound or CT preferable methods for diagnosis. Endoscopes can also be used diagnostically, allowing the surgeon to both visualize and treat the problem, often in the same session. Depending on the tools used in the central channel of the endoscope, stones or foreign bodies can often be removed, the gland can be irrigated, medications introduced, and stenoses can often be stretched open.

In 1990, German surgeons introduced the first successful application of endoscopic techniques to remove sialoliths (Journal of the American Dental Association, October 2006, Vol. 137:10, pp. 1394-1400). Since then, the tools have become smaller and more user-friendly. In the last 10 years, the techniques have been studied and practiced extensively in Germany and Switzerland particularly, where some U.S. surgeons have gone for training.

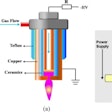

|

| Endoscope used for visualization and possible removal of salivary gland stones. |

The current state of technology involves a 0.8-mm diameter diagnostic endoscope for irrigation and visualization, and 1.1-mm and 1.6-mm scopes with a "working channel" that allows various tools to be inserted into them, such as a small basket for removing stones, forceps, a laser, a microdrill, or balloons to dilate stenoses. These scopes have about 45 degrees of flexibility, according to Dr. Gillespie. A scope set costs about $25,000.

Although most complications occur early in the learning curve, the risk of complications from endoscopic sialolith surgery is still very low (Laryngoscope, May 2008, Vol. 118:5, pp. 776-779).

"The hardest part is getting started," said Barry Schaitkin, M.D., a professor of otolaryngology and head neck surgery at the University of Pittsburgh. "The scopes, despite the fact that they're very small, have to go into something that's even smaller. So the learning curve mostly relates to being able to place the telescope into the ductal system without traumatizing the system, and that takes about 20 to 25 cases." Even after performing several hundreds of these, he still has about 3% of cases in which he is unable to do the procedure because he can't get the instrumentation into where it needs to go.

Not just for oral surgeons

The use of this procedure in clinical practice tends to be different in the U.S. than in Europe. In Europe, a standard part of the treatment algorithms involves extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) as a way to break up stones that are either very large or impacted, allowing for more strictly endoscopic removals, and many of the procedures are performed with only local anesthesia (Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, December 2009, Vol. 42:6). With fully endoscopic surgery, the patient can return immediately to a regular diet and full activity.

But the use of ESWL to break up salivary stones does not have regulatory clearance in the U.S. ESWL also has its own complications, such as knocking loose other dental work, Dr. Gillespie noted. In addition, because ESWL can involve a few 45-minute sessions three to four days in a row, it's often not cost-effective for patients to stay at an out-of-town medical center.

|

| Endoscope in use in operating room setting. Constant irrigation with saline allows for better visualization of the duct and easier advancement of the endoscope. |

As a result, in the U.S., diagnostic endoscopy is often combined with minimally invasive transcutaneous surgical techniques, necessitating general anesthesia and prior consent. Recovery times are also longer; with the combined approach using a small transoral incision, the patient can return to a regular diet but may need pain medication and oral rinses, plus three to four days of healing. If a significantly large transoral, transcervical, or facial incision must be performed, the patient will generally spend a night in the hospital with a drain in place and spend a week healing.

These surgeries have traditionally been performed by otolaryngologists and head and neck surgeons, and only a handful of clinics currently offer this procedure, according to Dr. Gillespie: the Medical University of South Carolina at Charleston, the University of Pittsburgh, the University of Indiana at Indianapolis, Washington University, and the universities of California at San Francisco and San Diego.

But training is increasingly being extended to U.S. dentists and oral surgeons. Dr. Gillespie, who has been designated by Karl Storz -- a leading provider of endoscopes used in sialolith surgery -- as a U.S. trainer of this technology, said the preliminary training can generally be achieved in a two- to three-day course, practicing on a human cadaver model. After such training, Dr. Gillespie believes many practitioners can begin to apply it to their practice.

"If they want to do it, it's really important to go and take a course," Dr. Schaitkin advised. "Lots of little things come up in a case that it would be helpful to have in your little armamentarium of tricks."

Copyright © 2010 DrBicuspid.com