Phantom bite syndrome -- a psychosomatic condition in which patients are preoccupied with dental occlusion -- can result in unnecessary dental procedures and even lead to new or worse dental problems. Researchers published details of three women with this syndrome in a recent case report in Frontiers in Psychiatry.

The women were strongly convinced that correcting their bite was the only way to resolve their symptoms, including symptoms in other body parts. Their perceptions could not be altered, and they underwent extensive, repeated dental treatments that only made their conditions worse.

"Early detection of psychotic disorders and prompt collaboration between psychiatrists and dentists are integral to help such rare PBS [phantom bite syndrome] cases with psychosis break this vicious circle," wrote the authors, led by Dr. Motoko Watanabe from the department of psychosomatic dentistry at Tokyo Medical and Dental University (Front Psychiatry, July 21, 2021).

A never-ending wrong bite

Phantom bite syndrome, also known as occlusal dysesthesia, is a condition in which individuals are in a state of "perpetual uncomfortable occlusions" that cannot be identified as dental findings or other orofacial disorders. Dentists should be aware of this rare hypochondriacal condition, learn about patients' histories of psychosis, and consult with mental health professionals, the authors wrote.

Indicators of phantom bite syndrome include the following:

- Repeated unsuccessful treatment

- Disparities between subjective sensory complaints and objective occlusion

- Belief that medically unexplained symptoms are solely due to occlusion

- Detailed descriptions of symptoms

- Blaming dentists who treated them previously

- High expectations for new dental care

Patients with phantom bite syndrome often undergo repeated orthodontic and dental treatment. They may also have a history of psychosis, such as schizophrenia, and may be prone to iatrogenic problems, according to the authors.

Details of the cases

In one case, a 70-year-old woman demanded orthodontic retreatment and complained of tightness and a cramped sensation in her teeth, uncomfortable occlusion, and neck and leg pain that she believed was caused by orthodontic treatment. She felt she needed additional orthodontic treatment to correct her problems.

Prior to her orthodontic care, the woman had a history of shopping for dentists, psychiatrists, and other doctors for more than 30 years. Eventually, she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Clinic physicians tried to explain that she had phantom bite syndrome and that any additional orthodontic treatment would worsen her condition. She had never received recommended ongoing psychiatric treatment and demanded orthodontic retreatment or to be referred elsewhere, the authors wrote.

Intraoral images of the 70-year-old woman. Clinicians replaced the bridge on her upper right molars with individual temporary crowns. All images courtesy of Watanabe et al. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Intraoral images of the 70-year-old woman. Clinicians replaced the bridge on her upper right molars with individual temporary crowns. All images courtesy of Watanabe et al. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.In two other cases, collaboration between dentists and psychiatrists resulted in the patients requesting and receiving fewer treatments that would have exacerbated their symptoms, Watanabe and colleagues noted.

A 38-year-old woman was referred to the clinic after consulting with many dentists and other specialists on complaints of an improperly aligned bite, an unstable mandibular position, and neck pain. She said the symptoms started without a trigger, and she had orthodontic treatment to deal with them.

The woman, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia, complained of occlusal discomfort and revisited with a complaint of abnormal occlusion due to excessive dental procedures. Despite this, she wanted more procedures.

An intervention led by the dentists and a psychiatrist helped the woman to understand that she had phantom bite syndrome. She was prescribed several medications and, eventually, started demanding fewer procedures.

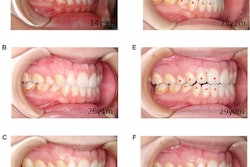

Intraoral images of the 38-year-old woman during her first visit (A) and revisit (B). Dental composite resin was constructed on her molars according to her demands. An anterior open bite can also be seen.

Intraoral images of the 38-year-old woman during her first visit (A) and revisit (B). Dental composite resin was constructed on her molars according to her demands. An anterior open bite can also be seen.Finally, a 48-year-old woman demanded occlusal adjustment for her improperly aligned teeth. After receiving orthodontic treatment, her symptoms worsened.

She underwent psychiatric treatment for 15 years with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. A collaborative approach from dentists and a psychiatrist, as well as medication, helped her better control her behavior. The woman demanded fewer treatments and was able to wait for appointments, according to the authors.

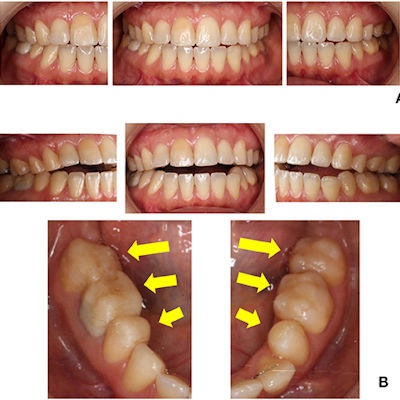

Intraoral images of the 48-year-old woman. All of the patient's teeth were in contact, but clinicians constructed dental composite resins on almost every lower tooth surface for occlusal adjustment after orthodontic treatment.

Intraoral images of the 48-year-old woman. All of the patient's teeth were in contact, but clinicians constructed dental composite resins on almost every lower tooth surface for occlusal adjustment after orthodontic treatment.Final thoughts

Persistent demands make it difficult for dentists to stop performing excessive procedures that will only exacerbate these patients' conditions. Better understanding of these conditions and collaboration between dentists and mental health professionals can help, the authors wrote.

"Especially for the cases with long psychotic history or young onset of psychosis and the presence of medically unexplained symptoms, dentists should be more cautious before providing orthodontic treatments," Watanabe and colleagues concluded.