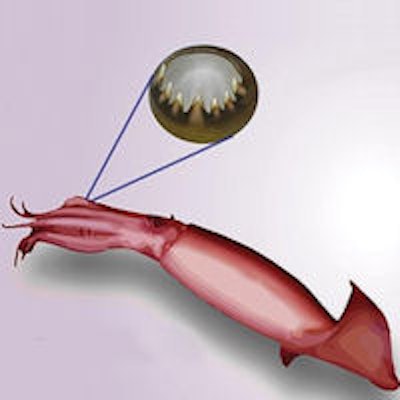

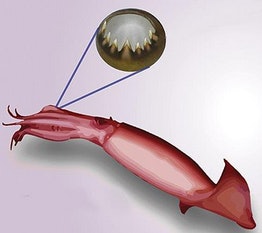

Squid tentacles are loaded with hundreds of suction cups, or suckers, that help the animal catch its prey. Each sucker, in turn, has a ring of razor-sharp "teeth," called sucker ring teeth (SRT), that are made up entirely of proteins.

Teeth on squid suckers are inspiring new materials for a wide range of applications from surgery to packaging. Above is a jumbo (Humboldt) squid with sucker ring teeth illustrated. Image courtesy of the American Chemical Society.

Teeth on squid suckers are inspiring new materials for a wide range of applications from surgery to packaging. Above is a jumbo (Humboldt) squid with sucker ring teeth illustrated. Image courtesy of the American Chemical Society.Now, a team of international researchers looking into these teeth have found that the proteins may form the basis for a new generation of strong but malleable materials that could be used to grow bone in reconstructive surgery, eco-friendly packaging, and other applications, according to a new study in ACS Nano (June 9, 2014).

Ali Miserez, PhD, an assistant professor in the College of Engineering at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, and colleagues explain that in previous research they discovered that sharp, tough sucker ring teeth are made entirely of proteins. That makes these teeth distinct from many other natural polymers and hard tissues (such as bones) that require the addition of minerals or other substances to perform the right functions.

The team already had identified one "suckerin" protein and deciphered its genetic code. They also found that this protein could be remolded into different shapes. Similarities in modular sequence design and exon-intron architecture suggest that suckerins are encoded by a multigene family.

“We envision SRT-based materials as artificial ligaments, scaffolds to grow bone, and as sustainable materials for packaging.”

In this new study, they identified 37 additional sucker ring teeth proteins from two squid species and a cuttlefish. The team also determined their architectures, including how their components formed what is known as "β-sheets." Spider silks also form these structures, which help make them incredibly strong. And just as silk is finding applications in many areas, so too could sucker ring teeth proteins, which could be easier to make in labs and more eco-friendly to process into usable materials than silk, according to the researchers.

"We envision SRT-based materials as artificial ligaments, scaffolds to grow bone, and as sustainable materials for packaging, substituting for today’s products made with fossil fuels," Miserez stated in a press release. "There is no shortage of ideas, though we are just beginning to work on these proteins."