A new study may shed light on the role of "microbial dark matter" in the progression of periodontitis and other diseases, according to results published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

While the human body contains 10 times more bacterial cells than human cells, scientists estimate that roughly half of the bacteria are difficult to replicate for research -- hence the term "microbial dark matter," explained a press release from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). A long-standing question is whether these bacteria contribute to chronic disease.

“Uncultivable bacteria presents a fascinating 'final frontier' for dental microbiologists.”

One such bacterial group of interest is candidate phylum TM7, which has been thought to play a role in inflammatory mucosal diseases because it is prevalent in people with periodontitis. However, despite its prevalence, the TM7 phylum has been difficult to cultivate and study.

Therefore, researchers from the UCLA School of Dentistry; the J. Craig Venter Institute in La Jolla, CA; and the University of Washington School of Dentistry decided to try to cultivate TM7x, a type of TM7 found in the oral cavity (PNAS, December 22, 2014).

In doing so, the researchers found the first known proof of a signaling interaction between TM7 and another bacterium, Actinomyces odontolyticus (or XH001), which is associated with mucosal inflammation.

"Once the team grew and sequenced TM7x, we could finally piece together how it makes a living in the human body," said co-author Jeff McLean, PhD, acting associate professor at the University of Washington School of Dentistry, in the release. "This may be the first example of a parasitic long-term attachment between two different bacteria -- where one species lives on the surface of another species gaining essential nutrients and then decides to thank its host by attacking it."

The researchers tested TM7x with other strains of bacteria, but only XH001 was able to establish a physical association with TM7x. This led the researchers to speculate that TM7x and XH001 might have evolved together.

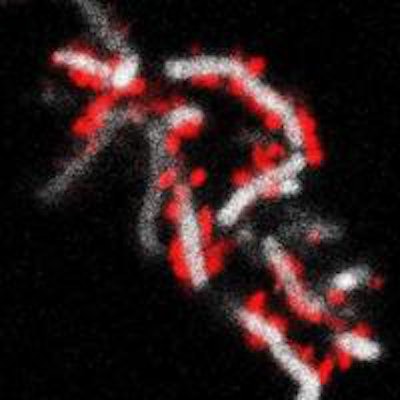

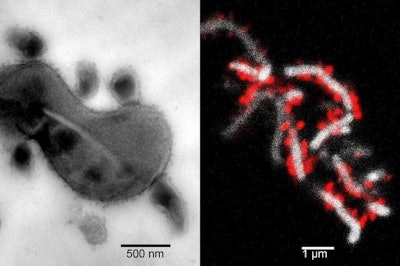

Left image shows the tight physical association between TM7x cells and XH001. Right image shows TM7x cells (red) attached to the surface of XH001 (white). Images courtesy of UCLA.

Left image shows the tight physical association between TM7x cells and XH001. Right image shows TM7x cells (red) attached to the surface of XH001 (white). Images courtesy of UCLA.Collected cultures allowed the group to study the degree to which TM7x contributes to chronic inflammation of the digestive tract, vaginal disease, and periodontitis.

"Uncultivable bacteria presents a fascinating 'final frontier' for dental microbiologists," said R. Dwayne Lunsford, PhD, director of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research's (NIDCR) microbiology program. "This study provides a near-perfect case of how co-cultivation strategies and a thorough appreciation for interspecies signaling can facilitate the recovery of these elusive organisms."

By infecting bone marrow cells with XH001 alone and then with the TM7x/XH001 co-culture, the researchers also found that inflammation was greatly reduced when TM7x was physically attached to XH001. The group plans to further study the relationship between TM7X and XH001 and how they jointly cause mucosal disease.

"This study provides the roadmap for us to make every uncultivable bacterium cultivable," noted senior author and UCLA professor of oral biology Wenyuan Shi, PhD.

The research was supported in part by NIDCR and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.