DrBicuspid.com is pleased to present the next installment of Leaders in Dentistry, a series of interviews with researchers, practitioners, and opinion leaders who are instrumental in changing the practice of dentistry.

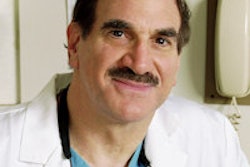

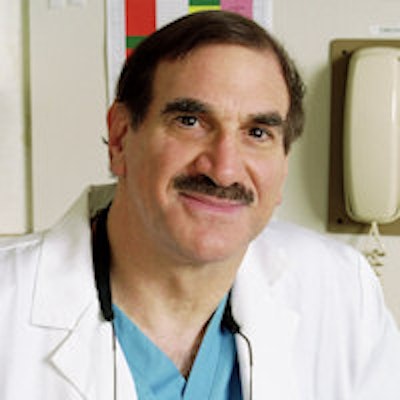

Stuart Froum, DDS, is the president of the American Academy of Periodontology, a clinical professor of periodontics and implant dentistry and the director of clinical research at New York University Dental Center, and a clinical assistant professor in periodontics at the Stony Brook University School of Dental Medicine.

In part 1, Dr. Froum discussed the lag in implant dentistry's adoption in the U.S. and the barriers before it. In part 2, we shift gears to learn when he feels it is appropriate to pursue an implant-centric treatment plan.

DrBicuspid.com: I thought this line from a recent Journal of Implantology press release was interesting: "Should a person's teeth be saved at all costs? Over the last decade, the answer has shifted from yes to no in favor of replacing diseased and damaged teeth with implants." Do you agree? Where is the threshold when it becomes necessary to abandon efforts to keep natural dentition?

Dr. Froum: In my opinion, the true goal of a dentist is to maintain the natural dentition for the life of the patient. That's what I was taught, and that's what I teach my students. Now, it's obvious that you can't do that in all cases. I'm a periodontist, so I treat many patients with moderate-advanced periodontal disease. Many of these teeth have questionable prognoses, but with proper treatment, the teeth can be saved.

Stuart Froum, DDS, president of the American Academy of Periodontology.

Stuart Froum, DDS, president of the American Academy of Periodontology.

The success rate for saving teeth in long-term studies in patients with proper periodontal care and good follow-up and who come in for regular maintenance is very high. Dentists collaborating with specialists have the skills to save teeth even if they have fractures, deep caries, or advanced periodontal involvement. If a tooth can be saved and function well, I always opt to save it. Many teeth today are being removed that can be saved with proper treatment.

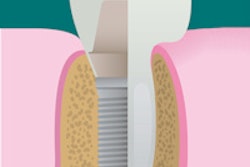

Implants are indicated where there aren't teeth or when a tooth cannot be saved. It's incumbent on the dentist to determine when that is. In those cases, where teeth are hopeless or have been extracted, implants are an excellent option because it gives the dentist the ability to place an implant and an implant-supported restoration on that implant in an area where a patient formerly would have had to have a removable bridge or have to prepare good, healthy teeth in order to put a fixed bridge in place.

The survival rate for the implant option is very high. It's difficult to identify overall long-term survival rates because, in many cases, implant companies have changed the surfaces and morphology of their products, making it hard to compare survival rates of newer rough-surface implants with machined or obsolete rough-surface implants.

In the long-term studies we do have, with the surfaces that are available today, the implant survival rates are pretty close to what they were with the machine-surfaced implants. For example, a 2012 study by Buser et al in Clinical Implant Dentistry and Related Research (December 2012, Vol. 14:6, pp. 839-851) reported a 10-year survival rate of 99%. Another five-year study by Jung et al reported a 97% survival rate, and they used five different implant systems: Astra Tech, Brånemark, ITI, 3i, and the Bioloks system. Even with a variety of systems, their survival rate was in the 90th percentile.

What I think these studies show is the potential to have high-survival rates with implants that are placed properly. I'm going to emphasize "that are placed properly" because in these studies, the procedures were done by dentists who were very experienced in implant placement treating patients who were screened and found to be low-risk patients.

What is the difference between success and survival?

Now we get to what we're talking about. The difference between success and survival is the following: strictly according to Albrektsson's criteria -- and this was updated by Roos-Jansåker, Buser, and others -- implant success is defined by the absence of any pain, infection, or mobility and an absence of radiolucency around the implant.

“The true goal of a dentist is to maintain natural dentition.”

When you take an x-ray, you want to make sure there isn't any radiolucency around the implant; that the x-ray shows that bone is in contact with or adjacent to the implant and there's no intervening space. Moreover, maximum bone loss should not exceed 1 mm the first year after restoration placement and 0.2 mm or less per year thereafter.

This was the definition of implant success; however, technically, this should be considered implant survival.

A functional, nonaesthetic implant may also be classified as a surviving implant. But an implant not placed in the proper position or one with an unaesthetic restoration that satisfies the above criteria may still be a survivor but not a success. An implant that is fractured or develops chronic soft-tissue inflammation leading to peri-implantitis may again be considered a survivor but not a success.

So the value for the typical clinician is that he or she can prepare the patient for the possibility of an implant outcome that is functional but not aesthetic.

Right, we talk about survival rates in implants, but that's not all you need to discuss. You have to remember that there are also a number of complications with implants and implant-supported restorations.

Patients always ask, "How long is this going to last?" In essence, they are asking how long their implant will function without problems. According to a study by Lang et al in 2004 in the International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants (Vol. 19:7), the five-year survival rate was 94%. The 10-year survival rate was 78%. These studies did not evaluate success, only survival. An implant that has a complication is not a success unless the complication is resolved.

There's a lot we've learned about the prevalence of implant complications. In one study by Pjetursson et al in Clinical Oral Implants Research (June 2007, Vol. 18:suppl 3, pp. 97-113), in the first five years, approximately 40% of patients had complications. In the 10-year study published in 2004 by Lang et al, biological and technical complications occurred in about 50% of the cases after 10 years in function.

When you place an implant, it may not last for the life of the patient. I include in my consent form to my patients that there are risks of complications. One serious implant complication is peri-implantitis. This occurs when there is inflammation in the soft tissue surrounding an implant leading to bone loss. Many patients don't realize that an implant, like a tooth, can develop disease in the tissues supporting the implant. Many practitioners don't realize until a patient returns with a biological or mechanical complication that these can and do occur. If they don't include these risks in their consent forms, many patients feel the dentist is at fault.

Any clinician placing or restoring implants has to consider possible complications and be prepared to treat or refer them. So getting back to your first question about how to get more dentists to place and restore implants in the U.S., I think you really want to ask how can we get more dentists to place and restore implants with high rates of implant success and who are prepared to treat any complications that can occur during placement or after restoration. And my answer is through education and comprehensive continuing education courses.