DrBicuspid.com is pleased to present the next installment of Leaders in Dentistry, a series of interviews with researchers, practitioners, and opinion leaders who are instrumental in changing the practice of dentistry.

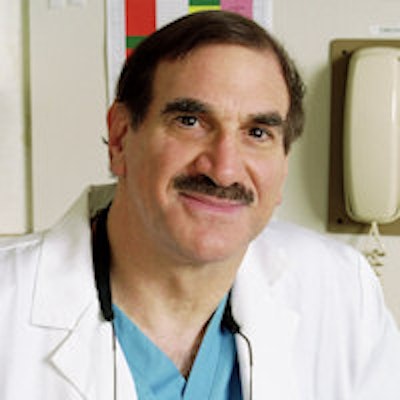

Stuart Froum, DDS, is the president of the American Academy of Periodontology, a clinical professor of periodontics and implant dentistry and the director of clinical research at New York University (NYU) Dental Center, and a clinical assistant professor in periodontics at the Stony Brook University School of Dental Medicine. We first learned of Dr. Froum during a symposium on implant complications hosted in San Francisco in May 2013. This is the first of a two-part interview.

DrBicuspid.com: Why do rates of implant placement in the U.S. lag far behind other developed nations?

Dr. Froum: Implant placement in this country lags behind by approximately a decade or more. There are several reasons that may explain this. First of all, in the U.S., many patients don't expect to pay out of pocket; they see dental care as a benefit that they receive. They've gotten their dental work done with co-payments and insurance for many years, and implants were not covered by most health plans. Therefore, dentists would recommend crowns and bridges as a less risky, less expensive option to patients, which, in many cases, were covered by the insurance companies.

Stuart Froum, DDS, president of the American Academy of Periodontology.

Stuart Froum, DDS, president of the American Academy of Periodontology.

Another reason is that many other countries do not have the specialty structure that we have in the U.S., where implants, for years, were done by periodontists and oral surgeons, not by general dentists (GDs). Most oral surgeons and periodontists either took early training programs given by the companies or were targeted by the companies to learn implants. These implant companies wanted to put their product in the hands of those who were most experienced in surgery to maintain high success rates and minimize complications. In other countries without specialists or with a limited number of them, where GDs performed all aspects of treatment, they were placing implants in conjunction with the scope of practice.

The third reason is that in the U.S., the general dentists were not the target group. They were the gatekeepers, and for a specialist to treat a patient in need of an implant, a dentist was the usual source of a referral. GDs, however, were a little hesitant to refer patients for several reasons, including the following: 1.) Many dentists were unfamiliar with implants but were familiar with crown and bridge. 2.) Crowns and bridges, in many cases, were covered by insurance. 3.) When a restorative dentist placed crown and bridges, they'd get paid for the complete restoration.

When they sent a patient for an implant to a specialist, the specialist placed the implant and was paid for the service. Then the patient usually had to wait a certain period of time before the implant was restored. The patient then returned to the GD for final restoration. However, many GDs feared the patient would not return to them for final restoration and would find a new dentist. Moreover, there was the fear that the patient might experience an implant complication and the referring dentist would lose the case.

I should also note that, according to some of the independent surveys I've read, general practitioners in the U.S. will be placing more implants than specialists by 2015. So the traditional referral/specialist collaboration will be changing. However, with more less experienced dentists performing surgery and placing implants, we may also see an increase in implant complications.

What are the barriers to adoption?

There has to be education about when an implant is indicated and when it is not. Education can't come from implant companies alone, but rather from courses given by academics and clinicians out there that are experienced with implant indications, risks, and procedures. And the courses should be comprehensive, not for a weekend, several days, or several weeks, but ones like those given at NYU Dental center where students (who are dentists) take a two-year full-time or four-year part-time course to learn all aspects of diagnosis and treatment. There are definite indications for implants, and there are definite times when an implant is not the option of choice. The choice of option requires education and experience.

For example, traditionally, a lower full denture was the treatment of choice for someone who was edentulous. Today, the minimum standard of care has changed from a full denture to a two-implant supported overdenture for fully edentulous mandibles.

Things are changing, but I don't know if the U.S. will ever "catch up" to the number of implants placed internationally because of the issue of nationalized healthcare versus insurance. As a dentist, I have reservations with a national healthcare program. I believe that it often results in a lower quality of dentistry, as seen in many countries outside of the U.S. This form of government insurance also leads to limited options when there is no coverage when restorations are placed for aesthetic rather than functional reasons.

In Canada, for example, it's very hard for a patient to get a CT scan for medical field diagnosis. Under their national healthcare system, CT scans and cone-beam scans, which are necessary for ideal diagnosis and proper implant placement in many cases, are also not covered by most government-sponsored insurance coverage. While a national health system sounds great, it does limit options. Until insurance companies are willing to pay for implants the same way they pay for removable or fixed bridges, for economic reasons in the U.S., you are going to see fewer people who can afford implant-supported restorations.

Is that currently considered a standard of care for implants?

Pretty close to it. In many cases, a CT scan can make the difference between an ideal implant position or a compromised situation. However, in many cases, with an experienced clinician, implants can be placed without a CT scan. Personally, I recommend a scan be taken for all implant placements since they provide 3D views of the receptor sites not available with 2D x-rays, and they can determine where and when bone augmentation procedures are necessary to place the implant in an ideal restorative position. They can also help deterrence when implants should not be placed due to anatomic limitations and proximity to vital structures (i.e., the inferior alveolar nerve).

In part 2, Dr. Froum addresses an ongoing debate in dentistry: when to extract and implant and when to save natural dentition.