The average individual already counts a toothbrush and floss among their tools for maintaining a healthy mouth. PhotOral, a new company based in Lexington, MA, is hoping that its unique technology will soon be added to that list.

Using concepts originally developed by researchers at the Forsyth Institute, PhotOral is working to create an intraoral device that uses blue light of the appropriate wavelength and dosimetry to restore homeostasis in dental biofilm, thereby improving oral hygiene noninvasively.

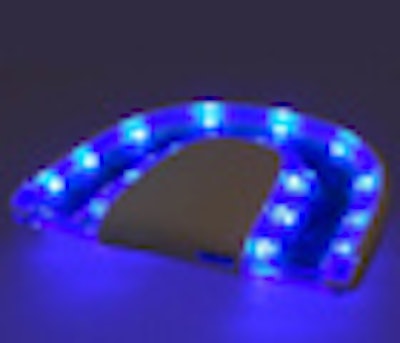

The PhotOral intraoral device targets pathogenic biofilm microorganisms. Image courtesy of PhotOral.

The PhotOral intraoral device targets pathogenic biofilm microorganisms. Image courtesy of PhotOral.

"PhotOral's blue light will seectively target key pathogenic bacteria in dental plaque," said Stamatis Astra, founder and CEO of PhotOral, which has an exclusive agreement with the Forsyth Institute to commercialize its oral blue light technology.

PhotOral was founded in the summer of 2011 by Astra, an entrepreneur, and last month the company presented a working model of the device at the Yankee Dental Congress. They are now working with designers to create a rechargeable device -- either a mouthguard or a lollipop-type design -- that will contain blue light-emitting diodes. The device is inserted into the mouth, and the user bites down to activate the light.

"This is a very new concept. It challenges the current opinion, which says, 'Go in there and eliminate all of the oral microorganisms,' " said PhotOral's founding scientist, Nikos Soukos, DDS, PhD, who is also director of the Applied Molecular Photomedicine Laboratory at the Forsyth Institute.

The technology was patented in September 2011, and PhotOral is now raising the capital to build a prototype for user testing. The goal is to have a product on the market in the next 12 to 18 months that will sell for about $90, according to Astra.

"It's going to be a consumer device designed to be used at home or in the car or anywhere so it doesn't have to be administered by a doctor," he said. "It can be done for one to two minutes a couple of times a day for the best results."

Why blue light?

Much of the research about the effects of blue light on bacteria in the oral cavity was conducted by Dr. Soukos, along with Max Goodson, DDS, PhD, a senior staff member at Forsyth.

Their investigations go back roughly 10 years, and in 2005 they demonstrated the susceptibility of key periodontal pathogens to blue light, suggesting the potential use of phototherapy as a targeted antimicrobial method to control growth within the dental biofilm environment.

“It challenges the current opinion which says, ‘Go in there and eliminate all of the oral microorganisms.’”

— Nikos Soukos, DDS, PhD, PhotOral

chief scientist

"We have found that broadband light (380 to 520 nm) rapidly and selectively kills oral black-pigmented bacteria (BPB) in pure cultures and in dental plaque samples obtained from human subjects with chronic periodontitis," they wrote in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (April 2005, Vol. 49:4, pp. 1391-1396).

They hypothesized that this killing effect was a result of light excitation of the endogenous porphyrins in the BPB.

"In healthy subjects, dental plaque remains stable for prolonged periods of time because of a dynamic balance among resident members of its microbial community," they wrote. "The primary goal of a strategy for disease prevention and control should be specific suppression of key pathogens."

Additional research found that using visible light to restore and maintain the homeostatic balance of oral microorganisms can yield microbiological, immunological, and clinical benefits.

"The potential applications of photodynamic therapy to treat oral conditions seem limited only by our imagination," Drs. Soukos and Goodson wrote in Periodontology 2000 (February 2011, Vol. 55:1, pp. 143-166).

Selective targeting

Based on these findings, the PhotOral device is intended to target the biofilm that resides in the dental pocket between the gingival tissue and the tooth, according to Dr. Soukos. This concept, "selective targeting," is already being explored in cancer research and other areas of medicine. Dr. Soukos sees opportunities for it in oral health as well.

"Light will target the dental pockets directly but also reflected light from the tooth will reach the pockets where dental plaque is," he added. "As light propagates throughout the plaque, certain microorganisms that produce and accumulate endogenous photosensitizing compounds will be eliminated."

Some of them are key pathogens that are involved in the development of periodontal disease. As a result of phototherapy, the proportions of these bacteria will be reduced and a microbial composition will be established that may be compatible with health, according to Dr. Soukos.

"These drug compounds already exist in the microorganisms, and we just activate them by light," he said. "This may be a rapid and easy way of restoring harmony in the dental plaque environment. Why do we think this? Because many patients have dental plaque and do not suffer from disease. The microbial composition of dental plaque in healthy human subjects is different than that in diseased subjects."

More studies are needed to demonstrate these concepts, he acknowledged.

"At this point we can only claim that we eliminate bacteria and thus can improve oral hygiene," Dr. Soukos said. "We have ongoing studies, but we don't have any therapeutic claim."

Still, he is excited about the future of this research.

"I think that for years to come people will explore this concept in many different departments and institutions in the academic community," Dr. Soukos said. "It will be a point of departure for emerging noninvasive technologies in the dental field."