Throat packs may not effectively prevent patients from ingesting blood during oral surgery or improve postprocedure nausea and vomiting, according to results from a randomized controlled trial published on August 6 in the International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery.

The use of oropharyngeal packs does not appear to benefit patients and evidence has indicated they can cause patients harm and contribute to poor outcomes; therefore, clinicians may want to reconsider whether they are worth using, the authors wrote.

"The results of this study call for OMS [oral and maxillofacial surgery] surgeons to question the use of throat packs in orthognathic surgery and other areas of practice," wrote the group, led by Dr. Kathlyn Powell from the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Dentistry.

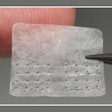

Oral and maxillofacial surgeons commonly use throat packs in patients under general anesthesia to reduce the amount of surgical fluid ingested, which can cause vomiting. Despite debated evidence about their ability to function as barriers after tracheal intubation, packs continue to be used.

Past studies have shown that throat pack use during surgery has led to poor outcomes, including tongue enlargement, airway obstruction caused by retained packs, and death. Dysphagia and throat pain also are common side effects.

In January 2020, the family of a 5-year-old girl filed a lawsuit against a Las Vegas dentist, claiming he set the child's mouth on fire during a routine dental procedure. The dentist reportedly was using a diamond bur to smooth the girl's teeth and it emitted a spark, causing the throat pack to ignite, according to the suit.

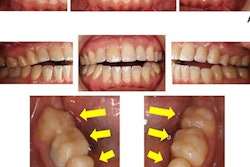

To explore whether throat packs really reduce blood ingestion and their effect on postoperative nausea and vomiting, the researchers conducted a single-blind randomized controlled trial that included 30 patients who were at least 16 and were undergoing orthognathic surgeries. Oropharyngeal packs were placed in half of the patients after intubation, while other patients did not receive any packing. Patients' gastric contents that they aspirated by nasogastric tube were viewed to determine whether they contained blood, the authors wrote.

There was no difference between the groups in quality of gastric contents or incidence of postprocedure nausea or vomiting. There were bloody gastric contents in approximately 67% of patients who received packing, as well as about 67% of those who didn't.

Meanwhile, about 20% of patients in the group that received packing and the same percentage of patients who did not get throat packs experienced nausea and vomiting two hours after surgery. Approximately 27% of patients in each group had those symptoms 24 hours after surgery, according to the authors.

Nevertheless, the study was limited by its small sample size, they noted.

Because the evidence suggests that throat packs do not decrease blood ingestion or improve postsurgery symptoms for patients, oral surgeons should question their use, the authors wrote.

Furthermore, "there are no universally adopted recommendations regarding their use that ensures patient safety," Powell and colleagues added.