Dental professionals need to learn about the latest developments in biofilms research to stay relevant and offer the best care possible, according to a presentation by Anne Guignon, RDH, MPH, at the recent California Dental Association's CDA Presents 2015 meeting in San Francisco.

Anne Guignon, RDH, MPH.

Anne Guignon, RDH, MPH.The presentation outlined how biofilms are much more complex than researchers previously thought, and how healthcare's knowledge of microbiology is rapidly changing. Consequently, we may need to rethink how we approach and treat biofilms, not only within dentistry but also within healthcare as a whole.

"We really don't know much about microbiology yet. ... It's much deeper and richer than we thought it was," said Guignon, who is also a columnist with RDH magazine. "When you understand it, you can deal with it more effectively."

New major players

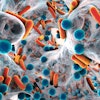

Despite the fact that 80% of all infectious diseases are biofilm-based, they are extremely difficult to treat, because biofilms are multifaceted, according to Guignon. Biofilms consist of various bacterial species with differing pH and oxygen requirements and divergent activities that work together to wreak havoc, help, or not do much at all. They are also largely composed of a strong slime that the microorganisms produce to protect themselves.

Additionally, scientists are discovering that a microorganism may act one way alone, but turn into a pathogen when grouped with others. Also, bacteria that researchers used to think were major players, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, may actually just be the gateway for more harmful ones.

"Here's what P. gingivalis does -- it messes with the host's immune system and causes it not to function properly," she explained. "It's not a key player. It's in there, but it's almost likely the gateway."

Furthermore, the research is rapidly changing. According to Guignon, the concept of dysbiotic communities, biofilms that are symbiotic but pathogenic, did not really show up in the scientific literature until a couple of years ago and have been increasingly prevalent in papers within the past six or seven months.

Effective treatments

Medicine's traditional response to biofilm has generally been to either cut it off or give the patient an antibiotic, which has proved to have unintended consequences. For example, antibiotics may help stave off an infection, but they can also change intestinal ecology, paving the way for other potentially deadly diseases, such as Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) colitis.

“They form wherever they want to. ... If we think we're going to get rid of all these microbes just by dosing with antibiotics, we can't.”

"They form wherever they want to. They're on your teeth ... and they cover the entire surface of the ocean. If we think we're going to get rid of all these microbes just by dosing with antibiotics, we can't," Guignon said. "Can you tell your patient, 'You can't take those antibiotics?' No. You can say that you're concerned and ask them to go back and talk to their doctor."

Instead, dental and other healthcare professionals can change the ecology and environment to make it difficult for microbes within biofilm to thrive and also slow growth, and, fortunately, dentistry has largely done this. Dentists and hygienists already cut back on the inflammatory environment that fosters growth of dysbiotic biofilms and are aware that dry mouth allows harmful bacteria to proliferate. They also use force to break biofilms apart.

"I can come in with my power-driven scalers, and you follow up with your power brushers," she said. "If you think you're going to get rid of 100% of them, you're wrong. Should you still try? Yes!"

Also, a flurry of newer techniques and tools are available to aid in the fight against pathogenic biofilms. For example, there are sweeteners that microbes can't break down; anti-inhibitors, such as xylitol, that make it difficult for microbes to stick; and even honey, which can inhibit biofilm formation.

Guignon is particularly enthused about the possibilities of the amino acid arginine, which microbes can break down to release ammonia and increase the pH levels of the oral cavity where cariogenic microorganisms cannot thrive. Studies have found that within a month of using an arginine-calcium carbonate toothpaste, subjects have healthier mouths, she said. Unfortunately, unlike many other countries, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved the use of arginine in toothpaste, but it is available through other products, such as in arginine bicarbonate-calcium carbonate chews.

Dentists and hygienists can also ask patients with weakened immune systems to come in more regularly for cleanings. Guignon said she did this starting decades ago, and she has watched patients get healthy and stay healthy.

However, not all traditional dentistry methods work. For example, some techniques, such as rinsing with mouthwashes or even flossing, may make a negligible difference when fighting biofilm.

"You've got bacteria protected by the slime from anything. If you think swishing with Listerine ... is going to do that much, it's not. It's a surface approach," she said. "Floss, by the way, is totally overrated. ... It's all about biofilm disruption; it's not about flossing."

Change the language

While dental professionals can do many things to combat biofilms, they need to tailor strategies to each patient, Guignon noted.

"You've got to be like Sherlock Holmes. If we treat people like cookie cutters, that's pretty boring," she said. "What are their risks? What are they willing to do?"

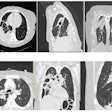

One way to educate patients about biofilm can be to switch up the language, from focusing solely on dental diseases to how bacteria can impact other parts of the body. For example, it can be helpful to explain that aspirating harmful bacteria in the lungs can lead to pneumonia, the leading cause of death in nursing homes. It can also be a helpful conversation starter to have biofilm images and diagrams decorating your exam rooms.

Despite changing the language and using pictures, not every patient wants to hear about biofilms and your message. In that case, Guignon recommends not wasting your breath.

"If they glaze over, then they're not ready to hear the message," she said.