Workforce changes alone cannot overcome the many barriers that prevent too many Americans from attaining good oral health, according to a new paper published by the ADA, "Breaking Down Barriers to Oral Health for All Americans: The Role of Workforce."

The authors warn that focusing on only this one barrier is "the policy equivalent of bailing a leaky boat." Future ADA papers will address other barriers, including the tattered public health safety net and the need to dramatically increase both disease prevention and financing, the organization announced.

The paper disputes the conventional wisdom of a coming shortage of dentists, projecting that later-than-predicted retirement, increased numbers of dental school applicants, and the opening of new dental schools will provide an adequate number of dentists through 2030.

Instead, the ADA argues that the challenges are the following:

- Placing dentists -- whether in private practice or government-assisted clinics -- in more underserved areas that otherwise cannot support a full-time dental practice

- Addressing issues that impede securing and keeping dental appointments, such as excessive paperwork, transportation, child care, and permission to take time off from work or school

"We know that the existing delivery model can accommodate millions more people, provided that we address administrative and financing barriers and workforce distribution," said ADA President Raymond Gist, DDS, in a press release. "Everyone deserves good oral health, and everyone deserves a dentist."

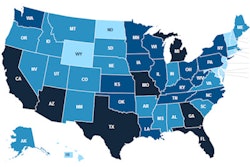

The ADA cites several examples in which states or municipalities have dramatically increased dental services provided to disadvantaged children through a combination of relatively minor funding increases and administrative reforms. These include the children's dental Medicaid programs in Tennessee, Alabama, and Michigan and the creation of a public-private dental clinic in Vermont.

The authors caution against a rush to create midlevel dental providers who, with as little as 18 months of training after high school, could be allowed to perform such irreversible/surgical procedures as extracting teeth. Such experiments, it argues, are likely to sap resources better directed toward proven methods for extending the availability of care from fully trained dentists.

It does, however, endorse such workforce innovations as the ADA's Community Dental Health Coordinator (CDHC) pilot project. CDHCs follow the medical community health worker model, providing health education and preventive services, identifying patients needing dental care, and helping those patients secure and keep appointments with fully trained dentists.