A man's incisor migrated to an unusual space -- the deep tissue below his chin. It required surgical removal, highlighting the need for secondary reviews and scans of facial trauma, according to a case report published online April 18 in Trauma Case Reports.

The case shows the importance of clinicians performing a second exam and panoramic radiograph, which is an x-ray of a patient's entire mouth, including the upper and lower jaw, in addition to a standard x-ray when a person visits an emergency room with a maxillofacial trauma, according to the authors.

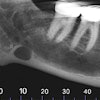

Orthopantomogram showing the displaced tooth lying at base of parasymphysis fracture (blue arrow). Fracture gap at parasymphysis base (black arrow). Image courtesy of SJ Shah et al. Licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Orthopantomogram showing the displaced tooth lying at base of parasymphysis fracture (blue arrow). Fracture gap at parasymphysis base (black arrow). Image courtesy of SJ Shah et al. Licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0"The displacement of [a] tooth through the fracture line is always a possibility and should be explored in event the tooth is not accounted for, in cases involving dental & maxillofacial trauma," wrote the group, led by Shahi Jahan Shah, DMD, of the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery at the College of Dentistry at King Khalid University in Abha, Saudi Arabia.

The challenge of displaced teeth

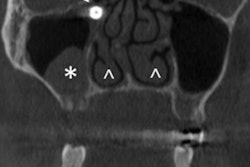

In many cases, the management of tooth displacements can be straightforward. Diagnosis and management become unpredictable when teeth migrate to unusual locations, including the maxillary sinus, nasal cavity, gastrointestinal tract, and airway. Displaced teeth and fragments of teeth that become embedded in soft tissue can lead to complications, including wound separation, fibrosis, and death.

Polytrauma cases can be especially tricky in those cases when primary exams are performed but necessary secondary surveys are delayed or ignored. This case, which involved a lower central incisor becoming unusually displaced into the submental space, was a result of an ignored secondary survey, according to the authors.

The plastic surgery department referred the man to the hospital's department of oral and maxillofacial surgery after the swelling to his submental space failed to respond to antibiotics and analgesics. Two months prior, the man had been in a traffic accident that resulted in injuries to his maxillofacial region and lower limb. A team of surgeons operated on the man, putting in miniplates to repair his panfacial trauma.

Weeks after the surgery, dental clinicians saw that the man had swelling with a round, firm, localized mass on his lower right chin area. The surgeons assumed his submental space was infected due to the parasymphysis fracture. They aspirated the lesion, which revealed a blood-tinged, thin, odorless mass of cells and fluid.

A panoramic radiograph was completed to evaluate the man's fracture site and the status of the miniplates. The more detailed radiograph showed a displaced central incisor lying at the base of the parasymphysis near the fracture site.

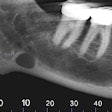

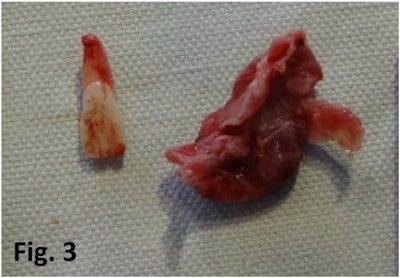

Dental surgeons decided to surgically explore the region by removing the unusually displaced tooth from the man's chin. An incision was done extraorally in the chin where the tooth was felt. Layer-wise dissection was performed. The tooth was contained by a thick fibrous connective tissue capsule, which came out whole along with the tooth inside, according to the authors.

The removed displaced tooth and its fibrous capsule. Image courtesy of SJ Shah et al. Licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

The removed displaced tooth and its fibrous capsule. Image courtesy of SJ Shah et al. Licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0The man was asked to return for a follow-up exam a week later and to discuss whether any future treatment was needed, but he never returned, the group wrote.

Lesson learned

The authors speculated that primary surgeons missed the tooth during their initial exam because they were not well versed in dentition or didn't know a second survey was needed. This man's case illustrates the importance of conducting a thorough secondary survey immediately after a patient with dental and maxillofacial trauma is considered stable.

Furthermore, this highlights the need for oral and maxillofacial surgeons to be named as part of multidisciplinary teams when these injuries arise, the authors noted.

A panoramic radiograph "should be part of every [emergency room] dealing with dental and maxillofacial trauma supplementary to the basic CT scan," they wrote.