Imagine you are at your physician's office and you're suffering from some flu-like symptoms. You notice other patients in the waiting room with a variety of illnesses and complaints. You then go into an examination room and describe your symptoms to the physician or physician assistant. A clinical examination and some tests are performed, and a prescription for medication is written for you.

Donald Tyndall DDS, PhD.

Donald Tyndall DDS, PhD.You go next door to the drugstore, hand the pharmacist your prescription, and have a seat in the waiting area. Over time you see the same people in the waiting room of your physician's office coming into the pharmacy asking for their prescriptions to be filled. From your casual conversations with them, you learn that everyone has been given the same prescriptions no matter what their disease or clinical evaluation. This, of course, comes as a great surprise to you as one would expect the physician to prescribe medication that fits everyone's particular symptoms, diagnostic test, and medical histories.

This scenario doesn't sound familiar doesn't it? Or does it? Strange as it sounds, an analogous situation occurs on a daily basis throughout the U.S. in most dental offices.

Surprisingly, many dentists prescribe the same radiographs for almost all their patients, regardless of their dental history, diagnostic tests, or clinical examination -- whether it is a full-mouth series or a panoramic radiograph with bitewings. In fact, many dentists will often prescribe radiographs before they examine a patient.

The same holds true for recall exams, where typically bitewing radiographs are prescribed for the same time intervals, either every six months or one year regardless of history and clinical presentation. This type of practice would not be acceptable with your physician, so why should it be acceptable for the dentist?

Guidelines

Dentists are not the only dental health practitioners practicing this form of healthcare. Dental schools also often prescribed the same radiographs for all patients regardless of their history and clinical examinations. Did I say prescribe? Yes, ordering radiographs for dental patients should be considered the same as prescribing a drug.

About now you may be asking, "Well, I don't know of any guidelines other than what I've been taught or practiced over the years." In fact, the dental radiographic selection criteria guidelines have been available since 1987. "The Selection of Patients for Dental Radiographic Examinations" guidelines were first developed in 1987 by a panel of dental experts convened by the Center for Devices and Radiological Health of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The ADA adopted these guidelines in 1989 and most recently updated them in 2012.

These selection criteria are designed to aid the dentist in deciding the most appropriate radiographic prescription for each patient, customized to their own health and dental history, as well as the results of a clinical examination. They were derived by a panel of experts using data from the clinical and scientific literature. They are also updated on a regular basis. In essence, the selection criteria are designed to limit radiographic exposure to patients for whom there is a reasonable probability that the resulting radiographs will provide useful information about disease or abnormality that is not evident clinically. In other words, the goal is to promote the appropriate use of dental radiographs. The purpose of this article is to provide the dental clinician with updated information on these guidelines in a way that is understandable and easily put into practice.

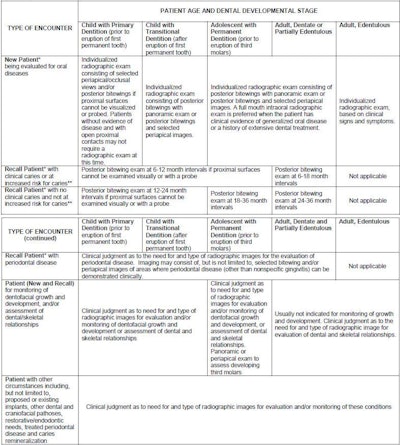

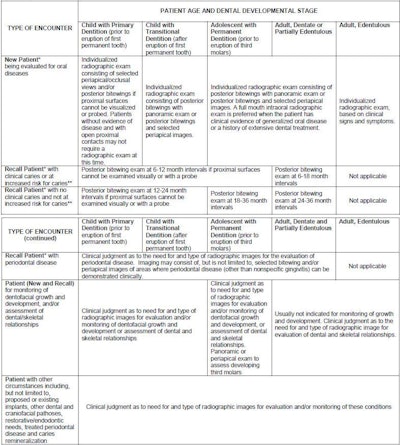

Just what are the selection criteria guidelines? They are expressed in a table format based on type of visit, dental status, and risk group. The types of visits include the following:

- The new patient

- The recall patient

- The patient in for assessment of growth and development

- "Other circumstances"

A few examples of other circumstances proposed are existing implants, other dental and craniofacial pathoses, endodontic/restorative needs, and remineralization of dental caries.

The dental status categories include child with primary dentition, child with transitional dentition, adolescent with permanent dentition, adult dentate and partially edentulous, and edentulous adult. The risk can be summarized as high or low risk for caries and high risk for periodontal disease.

These form a matrix or table of cells containing the actual recommendations. In addition, a list of six historical factors and 23 clinical factors when radiographs may be indicated is included to further illustrate proper use of the criteria. The guidelines do emphasize that the recommendations are subject to clinical judgment and may not apply to every patient.

The tables are listed below for easy reference (click to enlarge):

Reprinted courtesy of the ADA.

Now that we have reviewed the selection criteria, let's looks at some concrete examples.

Case examples

We will start with what is most common -- the new patient. A new patient comes to your office with very few restorations, no clinically evident periodontal disease, and no signs or symptoms of pathological conditions.

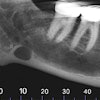

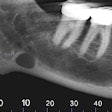

Recommendation: A panoramic radiograph with bitewings is appropriate. Both can be used as a guide for any further imaging such as a periapical radiograph of a tooth with a deep restoration. For the average new dental patient, a panoramic radiograph with bitewings is advisable.

In the situation in which the dentist doesn't have access to a panoramic system, then selected periapicals plus bitewings are advised. However, if the patient has clinical evidence of generalized dental disease or a history of extensive dental treatment, then a full-mouth series is most appropriate.

2 more cases

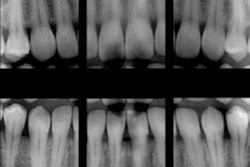

How about another common scenario -- the recall adult patient with low caries risk. In this case, bitewings can be taken anywhere from 24 to 36 months later. Up to three years? Yes that's correct. In most cases, the best predictor of the future is the past, and if a patient has not had any caries in the past, the probability of their having carious lesions is low for the future, at least until gingival recession begins to expose root structures.

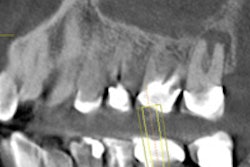

The third case is the patient with generalized disease and extensive dental treatment in the past. In this scenario, a full-mouth series is in order. The same would also be true for a patient with active periodontal disease.

In these cases, while a panoramic radiograph with bitewings might result in a lower radiation dose, it would not provide enough information to manage the patient properly. Here, the proper use of selection criteria would result in an increase in radiation dose, but the additional information would justify that increase.

We could go on and discuss many more case scenarios, but the point has been made here that each prescription of a radiographic examination should be customized for the individual patient based on his or her history, clinical exam, and dental needs.

One more item needs attention before this article is concluded: the issue of extra oral or panoramic bitewings.

As an oral and maxillofacial radiologist, I am often asked about the efficacy of bitewings obtained through panoramic units in which no intraoral sensor is used. As there are many instances in which bitewings are indicated in the radiographic selection criteria guidelines, it is reasonable to ask if panoramic bitewings are as diagnostically effective as those obtained with intraoral sensors.

To begin with, many oral and maxillofacial radiologists agree that panoramic bitewings are a worthy goal to pursue, but there is currently not enough clinical and scientific evidence showing that they are as effective as those obtained with intraoral sensors. There is more work to be done in this area, and, hopefully, one day we will see extra oral bitewing systems that are as efficacious as those obtained intraorally.

Also keep in mind that, if they are good at detecting caries, it does not necessarily mean they are good at detecting other forms of dentoalveolar disease. Again, much research needs to be done in this area.

In conclusion, the ADA-approved radiographic selection criteria guidelines should be reviewed by practicing dentists and applied in their dental practice, customizing each radiographic exam prescription for each patient based on his or her needs. As a baseline, a panoramic radiograph with intraoral bitewings is considered a reasonable starting point for the average new patient in a typical dental practice. For more complex needs, a full-mouth series of radiographs is appropriate. As radiographic imaging technology advances, such as cone-beam CT and novel panoramic imaging technologies, these guidelines will be updated as directed by scientific and clinical research.

Donald Tyndall, DDS, PhD, is a professor in the department of diagnostic sciences at the University of North Carolina School of Dentistry. He has been the director of radiology for the School of Dentistry since 1988.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of DrBicuspid.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular idea, vendor, or organization.