A 2-million-year-old mishap that befell two early members of the human family tree has provided the most robust evidence to date of what at least one pair of hominins ate (Nature, June 27, 2012).

Almost 2 million years ago, an elderly female and young male of the species Australopithecus sediba fell into a sinkhole, where their remains were quickly buried in sediment. In 2010, anthropologist Lee Berger of the Institute for Human Evolution at the University of the Witwatersrand and his colleagues described the remains of this newly characterized creature.

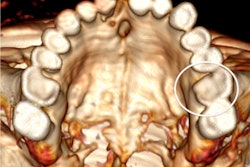

Now a team of scientists has studied the teeth of these specimens, which proved to have unique properties because of how the hominins died. Since the two individuals were buried underground and quickly encased in sediment, parts of the teeth were even preserved with a pocket of air surrounding them.

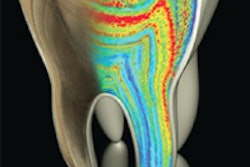

Because of this, the researchers were able to perform dental microwear analyses of the tooth surfaces and high-resolution isotope studies of the tooth enamel on these well-preserved teeth. In addition, because the teeth had not been exposed to the elements since death, they also harbored another thing not discovered before in early hominins -- areas of preserved tartar buildup around the edges of the teeth. In this plaque, the scientists found phytoliths, bodies of silica from plants eaten almost 2 million years ago by these early hominins.

Using the isotope analysis, dental microwear analysis, and phytolith analysis, the researchers studied the diet of these two individuals, and what they found differs from other early human ancestors from that period. The microwear on the teeth showed more pits and complexity than most other australopiths before it. Like the microwear, the isotopes also showed that the hominins were consuming mostly parts of trees, shrubs, or herbs rather than grasses.

The phytoliths gave an even clearer picture of what they were consuming, including bark, leaves, sedges, grasses, fruit, and palm.