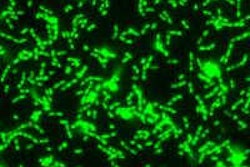

As genetic tools have improved and made it possible to confirm the presence of the bacteria responsible for some of the diseases observed in ancient human remains, researchers have turned their attention to one of the principal bacteria that causes caries.

International researchers have sequenced genetic material from Streptococcus mutans in populations from the past for the first time, leading to the discovery that S. mutans has increased the changes in its genetic material over time, according to a new study in Proceedings of the Royal Society B (July 23, 2014). These changes possibly coincided with dietary changes linked to humanity's expansion.

The discovery was announced by researchers from the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) in Spain and the National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity in Mexico.

The researchers studied the bacterium in 11 individuals from the Bronze Age up to the 20th century, from locations in Europe and both pre- and postcolonial America. The oldest case is that of an individual dating from 1,200 B.C. from a burial chamber in the Montanisell Cave in Lleida, Spain, and the most recent one is from the beginning of the 20th century.

“This indicates a population-based expansion by the bacterium that may have occurred in parallel with the demographic expansion of humans.”

"The relationship is well known between the increase in frequency of caries and the dietary changes that occurred in the Neolithic, or with the European discovery of America, with the large-scale introduction of sugarcane to Europe, or the Industrial Revolution, but what was not known was whether this change happened jointly with changes at a genetic level [in] this bacterium," explained the article's principal author, Marc Simón, a trainee researcher in the UAB biodiversity doctorate program, in a press release.

"We saw that, in the most recent populations, genetic diversity was greater; to us, this indicates a population-based expansion by the bacterium that may have occurred in parallel with the demographic expansion of humans," Simón continued. "We think that this increase took place in the Neolithic. Currently, the oldest individual we have analyzed is from the Bronze Age, but we might actually be witnessing the continuation of this process. In the future, we hope to be able to work with even older samples in order to corroborate our hypothesis."

Researchers have long sought evidence for the historical relationship between caries and humans. This study may provide that, along with suggesting ways in which distinct historical moments may have contributed to this relationship. They found that an increase in genetic diversity has been produced, especially in the fragment of a gene that codifies a virulence factor known as dextranase.

"It is important to know how the gene varied in the past in order to predict models of evolution for caries virulence, to know whether these changes were a response brought about in order to adapt better to changing environments or even to other parts of the human body, such as the gastrointestinal tract, or if they changed to become resistant when conditions of hygiene improved, etc.," noted Assumpció Malgosa, a researcher in biological anthropology at UAB who coordinated the study. "Knowing how they reacted in the past in different situations can provide us with an idea of how they will do so in the future in similar circumstances."