Squirrels, beavers, and other rodents have orange-brown front teeth that may be key to developing oral care products that better protect human tooth enamel and ensure that restorations last longer. The study was published on April 17 in ACS Nano.

The enamel of the animals' incisors contain acid-resistant, iron-rich material that protects their teeth but doesn't give them their unusual color, opening possibilities for improving human dentistry, the authors wrote.

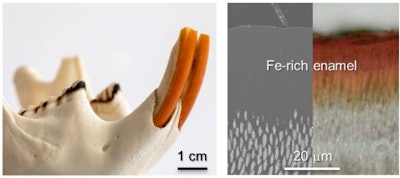

The structural and chemical optimizations of rodents' incisor teeth surpass those found in human teeth, Srot et al reported. Notably, the outer layer of their enamel is enriched with iron, which serves as an insulating barrier that protects the incisors from environmental factors. Image courtesy of Srot et al. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

The structural and chemical optimizations of rodents' incisor teeth surpass those found in human teeth, Srot et al reported. Notably, the outer layer of their enamel is enriched with iron, which serves as an insulating barrier that protects the incisors from environmental factors. Image courtesy of Srot et al. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

"The functional significance of acid-resistant iron-rich enamel and the understanding of the underlying coloration mechanism in rodent incisors have far-reaching implications for human health, development of potentially groundbreaking dental materials, and restorative dentistry," wrote the authors, led by Vesna Srot of the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research in Germany.

Though enamel is the hardest tissue in the human body, it's more stiff in rodents. The incisors of rodents are not only ever growing, but they have an extra outer layer of acid-resistant, iron-rich enamel. Previously, researchers surmised that this iron material also was responsible for the remarkable orange and brown hue of many rodents' teeth. However, the microscopic structure of their teeth had yet to be fully characterized.

To better understand what comprises the enamel of rodent incisors, high-resolution images of teeth from beavers, squirrels, marmots, mice, and other rodents were captured. Direct atomic-scale imaging and nanoscale spectroscopies were used to reveal the elemental composition and color transmission of the enamel.

The imaging revealed that cells that synthesize the components of enamel produce up to 8-nm wide particles of ferritins, which are iron storage proteins and the source for iron ions in matured enamel. As enamel fully grows and solidifies before tooth eruption, ferrihydritelike material that contains iron proceeds into the outer layer of enamel, occupying empty spaces between calcium-containing hydroxyapatite crystals. Additionally, the microstructure of the iron-rich enamel contain extended nanometer-sized pockets that are filled with small amounts of the ferrihydritelike material, which helps resist acid.

Furthermore, the unique color of rodents' incisors originates from a slim layer of inorganic minerals and aromatic amino acids and not from the filled pockets in the enamel, like researchers previously suspected.

This discovery suggests that adding small amounts of ferrihydritelike or other colorless biocompatible iron minerals to everyday oral care products may provide remarkable safeguarding for human enamel. Also, adding small amounts of iron hydroxides into synthetic enamel may lead to advanced restorations for human teeth.

"Such advancements have the potential to revolutionize dental care and provide innovative solutions for long-lasting and resilient dental restorations," Srot et al wrote.