Clinicians corrected a woman's class III malocclusion and cured her of chronic orofacial pain without the need for surgery. They described their use of an occlusal splint and fixed restorations in a case report published on October 25 in the Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry.

Adults with malocclusion with a skeletal component, such as mandibular prognathism, often undergo corrective surgery of the jaw and orthodontic treatment. However, this approach becomes complicated for patients who also experience temporomandibular disorders (TMDs), as invasive and irreversible treatments such as surgery are not the best options.

When both severe malocclusion and TMD pain occur, patients have limited capability to adapt to occlusal changes. Therefore, other treatment paths should be considered, according to the authors of the case report.

"Pain and dysfunction should be approached with functional pretreatment, and the patient's adaptation to substantial occlusal changes should first be tested with a reversible procedure," wrote the group, led by Dr. Christopher Herpel, a researcher in the prosthodontics department at Heidelberg University Hospital in Germany.

In the current case, a 57-year-old woman was referred from the oral and maxillofacial surgery department for treatment planning. She presented with severe pain in her masticatory muscles and limited jaw mobility, and she reported having chewing difficulties since childhood.

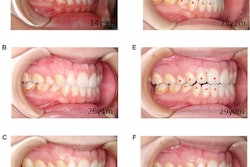

To close her mouth in the maximal intercuspal position, she needed to protrude her mandible, with the mandibular incisors completely covering the upper jaw incisors. When she was in a relaxed mandibular position, her molars had no contact, and she could not use them to chew.

For most of her life, the woman chewed primarily with her incisors. Over the years, her restrictions had worsened, and she constantly experienced pain, according to the authors.

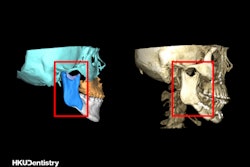

Imaging revealed that the woman had residual dentition with fixed partial dentures in class III malocclusion with anterior reverse articulation and excessive vertical overlap. Despite a fixed dental prosthesis, her occlusion never changed.

Her profile showed a moderately prominent chin and a pronounced lower lip. The patient's class III malocclusion was due to a skeletal component, which forced protrusive movement of the jaw to achieve maximal intercuspal position.

The team diagnosed the patient with myofascial pain of the masticatory muscles after conducting a functional examination. Also, the patient reported she had worn an occlusal device at night for two years, but she experienced little relief from her symptoms.

Due to this chronic pain, the clinians had concerns about surgical treatment. Instead, they created a custom removable device for the third and fourth quadrants of her teeth. The two parts of the device were connected by a lingual bar.

For three months, the patient wore the customized device for 24 hours a day. Within two weeks of wearing it, she felt some relief from her symptoms, the authors reported.

After three months of wearing the device, her pain intensity was significantly reduced. The clinicians then planned her nonsurgical occlusal treatment. Her existing partial dentures were removed, and all teeth except for her mandibular anterior teeth were prepared for crowns.

The patient's masticatory adaptation was good after four weeks. Restorations made from monolithic zirconia were placed with glass ionomer cement. To correct her open bite between her right canines, composite resin was placed on her lower jaw right canine.

At a three-month follow-up visit, the woman had stable occlusion and no pain, the authors wrote. The case demonstrates that creative, nonsurgical treatment options may be available for patients with severe malocclusion and TMD.

"Most patients with myofascial orofacial pain can be successfully treated with conservative and reversible treatment," Herpel and colleagues concluded.