A steady change is taking place in the restoratives market as patient and practitioner preferences for dental materials evolve.

Not surprisingly, the use of gold continues to diminish, according to Michael DiTolla, DDS, director of clinical education at Glidewell Laboratories.

Michael DiTolla, DDS.

Michael DiTolla, DDS.

"In 2011, gold was 3.5% of the restorations that we did here and that dropped another half percent [in 2012]," Dr. DiTolla said. "Compare that to 2007, where it was 8% of the crowns that we've made, so that's a significant drop over five years."

And it is not just the rising cost of gold, which was pitched and purchased as a less volatile investment in the midst of the global economic downturn. In fact, the gold market continues to be quite volatile, dropping 9.4% in on day in mid-April, the largest plunge in 30 years, according to news reports. Even so, gold's gains during the last 10 years are still far greater than the recent loss.

Dr. DiTolla believes that the decline has more to do with the consumer than the price.

"Take a theoretical situation where gold is $200 per ounce," he said. "Dentists would be buying it personally and sticking it in a safe, but I don't think those [crown] numbers would go up much for us. Maybe a percent or two, but there are enough patients that don't want it in their mouth. Price is part of it but so is push back from the consumer."

That push back, combined with the actual price of gold reaching nearly $1,800 per ounce as recently as October and currently hovering around $1,500, is a "recipe for the unfortunate death of a restoration," according to Dr. DiTolla.

PFM crowns

Use of porcelain fused-to-metal (PFM) crowns also has declined.

"It always shocks dentists to hear this, but the PFM made up 65% of crowns we made in 2007, and in 2012 it went down to 20%," Dr. DiTolla noted. "That's a precipitous drop for a crown that was the default crown for crowns and bridges for 40 years. An amazingly rapid change in dentists' prescribing habits."

“We've been hearing about the death of the PFM for a long time.”

He attributed the continued usage of PFMs to dentists who are patiently awaiting the data from researchers examining the durability of all-ceramic materials. Dentists who have dealt with underachieving materials in the past are cautious about making the switch.

"We've been hearing about the death of the PFM for a long time," Dr. DiTolla acknowledged. "Then we'd try some of these all-ceramic systems and we'd have a lot of fractures upsetting the dentists and patients; and nobody wins when a crown breaks. Dentists have been burned over the years by some of these systems, so it's surprising how quickly the switch is taking place."

That change is due in part to the success of monolithic restorations, such as IPS e.max by Ivoclar Vivadent, which hit the market in 2007, he noted. While the two first incarnations of the product as a bilayered material proved to be flawed and prone to chipping, the company changed its approach.

"The third time, they released it as a monolithic material made of lithium disilicate and that's when it took off," Dr. DiTolla noted. "It gave us the idea for BruxZir, to take zirconia coping out from underneath a porcelain-fused-to-zirconia crown and just build the whole crown out of zirconia."

Class II composites

While the shift is gaining momentum, many practitioners are taking a wait-and-see approach. Meanwhile, Gordon Christensen, DDS, MSD, PhD, said in no uncertain terms during the 2012 ADA General Session that composites should last longer.

"Class II composites only last about seven years. I think we can do better," Dr. Christensen said at the time, while noting that typical revenue for a class II composite is $200. "Maybe that's why they don't last so long -- we're in a hurry to get it over with and move onto something that will earn an income. Otherwise, we may have to drive a cab at night."

Dr. DiTolla agreed and stated that direct placed large class II restorations is an area of restorative dentistry that needs improvement. However, he predicted that it will be some time before a better solution arrives.

"We have really good solutions for small and large cavities, but that middle size, so far there's not a lot exciting on the horizon," he said. "Part of what Gordon is looking for is something the dentist can do in one appointment to help keep costs down. There's no revolution about to occur in indirect place composites. It's a void we'll have for maybe the next decade or so."

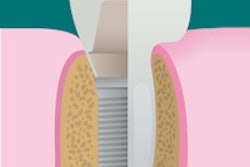

Rise of zirconia

Zirconia-based restoratives also are growing by leaps and bounds.

"Zirconia has been the fastest-growing product that we've ever had here at the lab," Dr. DiTolla stated. "If you look back to 2007, zirconia-based restorations were 13% of the crowns we made. Zirconia has gone from 13% to 56% of our crowns and is now the largest category of crown that we make."

The exponential growth of BruxZir since its 2009 introduction was credited in part by Dr. DiTolla to its extreme popularity among young dentists. Dentists are "bullish" on zirconia and are ordering it in record numbers. The appeal to patients is in its appearance and as an alternative to cast gold. While three-year test results have not been published, there is little to suggest that the material will fall out of favor after reviewing the one-year performance of it.

"Dr. Christensen and his research group have been testing it and recently came out with their one-year results and they are promising; Dental Advisor recently released an 18-month eval and its doing well," Dr. DiTolla stated. "The five-year mark is an important mark in the clinical history of any product, so when we're five years out we'll breathe a little sigh of relief. Problematic products start to fail even in the first year or two, so we're optimistic."

As the results of those tests start to roll in, once-popular materials are likely to see their use further reduced.

Amalgam going away?

And what about that old standby, amalgam? Having become one of the most controversial materials in dentistry, it is already banned in some European countries.

U.S. legislation regarding amalgam may be influenced by European stakeholders of an antiamalgam persuasion. At a United Nations forum in Geneva in late January, the United Nations Environmental Programme unveiled a draft treaty -- known as the Minamata Convention on Mercury -- that includes a section specific to dental amalgam. The treaty, which has been four years in negotiation and will be open for signature at a special meeting in Japan in October, addresses the direct mining of mercury, export and import of the metal, and safe storage of waste mercury.

The treaty also pushes for the phasedown of dental amalgam, such as incentivizing amalgam alternatives through insurance, focusing on these alternatives in dental schools, restricting encapsulated dental amalgam, focusing research on improving alternatives, and promoting dental caries prevention. In addition, the treaty specifies a best-practice approach to minimizing the release of waste dental amalgam, currently typified by the use of amalgam separators in dental practices that permit the capture, separation, and eventual recycling of mercury.

And the proposal elicited a positive reaction from the ADA. However, its effectiveness and a lack of legislation limiting its use in the U.S. so far indicate that amalgam will continue to play a role in restorative dentistry.

"I think there definitely is still a place for amalgam," Dr. DiTolla said. "I lecture around the country and the majority of dentists still use it -- maybe not as their only direct restorative. But those larger restorations, they feel more confident with the long-term clinical success of amalgam. If you look at what Gordon was saying about the longevity of the typical class II composite restoration, if you look at the amalgam restoration, it lasts long beyond that."

It's also affordable, which is of significant importance to the typical American family that has an average household income of around $50,000 annually, he noted.

"For patients going to dental practices that aren't a 'boutique' practice, I think amalgam is going to be around for a long time," he said.