Keeping root canals free of harmful biofilms is problematic at best. A new review article in the Journal of Oral Microbiology (September 16, 2016) points a way toward a new and safer treatment approach.

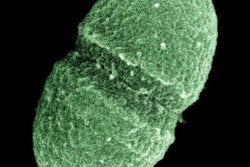

Endodontic biofilms are a common biological cause of root canal disease and infection. While the biofilms and pathogens that contribute to these infections, including Enterococcus faecalis, can be identified, getting rid of them is not as easy.

The authors from Israel reviewed the use of new treatments using bacteriophages against E. faecalis in root canals and how effective they are.

"The difficulties in destructing biofilms necessitate development of alternative ways to prevent and control biofilm-associated clinical infections," wrote the authors, led by Leron Khalifa, PhD, from the Institute of Dental Science at the Hebrew University Hadassah School of Dental Medicine.

Fivefold reduction

E. faecalis is a difficult-to-eradicate pathogen present in up to 77% of persistent infections, and it is a common reason why root canal treatments fail, according to the authors. The most difficult E. faecalis strains to treat are its biofilm-forming vancomycin-resistant enterococcus strains. While bacteriophages, known as phages, have been highly effective against biofilm and multidrug-resistant bacteria, their effectiveness both in dentistry and against E. faecalis biofilms in root canals is almost unexplored, the authors noted.

The most commonly used current treatments against E. faecalis and other root canal infections involve using biomechanical cleaning, root canal shaping, and disinfection, followed by sealing and crown restoration to remove bacteria. In contrast, a bacteriophage is a "virus that specifically targets and destroys disease-causing bacteria by invading bacterial cells, disrupting their metabolism, and causing lysis," according to the authors. These phages replicate and kill the biofilm. When the "target bacteria" are gone, the phage no longer has a host, so it is eliminated from the mouth.

“These results indicate that phage therapy might be a worthy additive solution in combating E. faecalis biofilms in root canals.”

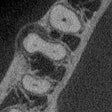

While more than 25 phages have been isolated against E. faecalis, only the one known as EFDG1 has been tested on E. faecalis biofilms, the authors noted. This phage, which they report is isolated from sewage water, was "very efficient" in a 2015 study in "nearly eliminating" a 2-week-old E. faecalis biofilm of approximately 100-µm thickness.

The same study also showed a fivefold reduction within seven days in the phage-treated samples compared with the untreated biofilms, which were stable and showed no reduction.

In another study, EFDG1 was also tested in post-treated root canal infections using an ex vivo two-chamber bacterial leakage model of human teeth. Those researchers measured bacterial leakage from the root apex and found that the obturated root canals subjected to EFDG1 irrigation resulted in a "dramatic reduction in bacterial leakage compared with the conventional sample."

Worthy addition?

While initial results on the phage-bacteria interaction have been positive, more research is needed, according to the review authors. They also noted that the small number of phages that can specifically target oral bacteria means more research and isolation of phages that can act against oral pathogens are necessary.

"These results indicate that phage therapy might be a worthy additive solution in combating E. faecalis biofilms in root canals where all other anti-infective and aseptic technique strategies, including the current use of increased apical preparation sizes, and inclusion of chlorhexidine in combination with sodium hypochlorite, fail," the authors concluded.