There comes a time in every partnership when the partners no longer see eye to eye, or the expectation of the longevity of the partnership is no longer as it was. Partners may not be of the same age, and, while one is contemplating scaling down his production, or even retirement, another has experienced a recent divorce that has once again made him hungry to win back the losses associated with the division of assets from the litigation of a failed marriage. A third partner might be happy with the way things are, but can certainly read the discontent of the other two partners.

Thomas Climo, PhD, is a dental practice management consultant and a past professor of economics in England.

Thomas Climo, PhD, is a dental practice management consultant and a past professor of economics in England.

So, what to do?

The first and most important matter is for the partners to realize they have only one of three directions they can go:

- Two partners can buy out one partner.

- One partner can buy out the other two partners.

- The three partners can all agree to sell to a fourth party not associated with them.

The second step is to hire an economist who specializes in the valuation of dental practices to perform a "disassembly valuation."

A good disassembly valuation consists of a series of columns detailing the move from the net income of the year of valuation -- usually the prior year -- of the existing three-partner dental practice to one of the three sets of circumstances identified above. In all, four columns of valuations are needed:

- Column 1: Existing financials containing prior-year net income and prior-year practice valuation off this net income

- Column 2: The effect on prior-year net income and practice valuation from removing one partner and recasting the practice as a two-member partnership

- Column 3: The effect on prior-year net income and practice valuation from removing two partners and recasting the practice as a solo practice

- Column 4: Market valuation of the dental practice as "for sale" to an independent fourth party

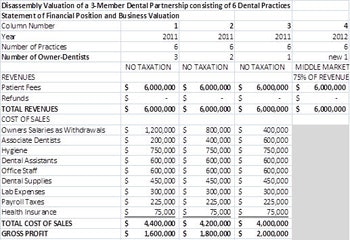

For a sample three-member dental practice partnership, I have created the following spreadsheet. (Click the image below to view the full spreadsheet.)

','dvPres', 'clsTopBtn', 'true' );" >

Click image to view full spreadsheet.

Disassembly valuation of a three-member dental partnership consisting of six dental practices. Chart courtesy of Thomas Climo, PhD.

The partnership has three dentists and six practices. Each practice collects $1 million per annum, or $6 million gross. Cost of sales and operating expenses are the same over the first three options of Columns 1 to 3 other than for the replacement of owner withdrawals at $400,000 per partner with an associate dentist at $200,000. Production remains the same.

The switch from partner(s) to associate(s) benefits the move from Column 1 to 2 by $200,000 and from Column 1 to 3 by $400,000. These "savings" transfer directly to the overall practice bottom lines.

The net income in Column 1 is less than Column 2 by $200,000 and less than Column 3 by $400,000.

As associate dentists replace partners, business valuation of the practices moves up since net income moves up.

(As an aside, it is often recommended to use earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization [EBITDA] instead of net income for business valuation, the presumption being that with EBITDA we are measuring economic and not accounting profit. But any economic profit must include the cost of capital and the degradation over time of longlife assets. Cost of capital is dealt with in the classic valuation formula. However, to quote Warren Buffett: "Does management think the tooth fairy pays for capital expenditures?" Depreciation, while not exact in its accounting formulation, remains the most practical method available. In light of this, the valuation formula used in this and all of my articles prefers net income over EBITDA.)

Column 4 is its own standalone market valuation number and drives itself from the same reasoning of another prior DrBicuspid.com article of mine. For whatever reason, market valuations in dentistry are pegged against the prior year's revenue, usually between 60% for low-margin practices up to 90% to 95% for high-margin practices. Prior-year revenue of 75% is the most common percentage I have witnessed in an assessment of more than 100 dental practice purchases, and so I employ this percentage for the Column 4 valuation.

There is no question that one partner ought to buy out the other two on the basis of the disassembly valuation report. However, this often won't happen, either out of fear of raising the money and the personal guarantee that attaches to this raise, or from simple fear that the practices may actually be worth more than the money the departing partners are putting in their pockets.

Thus the fourth alternative of selling to a stranger often results, and the partners have left $2.7 million on the table as "added value" to the in-coming buying dentist.

Thomas Climo, PhD, is a professor emeritus of accounting and finance at a major university in the U.K. He has published extensively about the importance of modern managerial and financial decision-making for dentistry. He is a consultant to corporate and solo practitioner dental practice management companies in the states of Arizona, California, Connecticut, Nevada, New Hampshire, New York, and Massachusetts. He can be reached by email at [email protected] or by telephone at 702-578-2757.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of DrBicuspid.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular idea, vendor, or organization.