Imagine two students, Abel and Cain, graduating from the University of Southern California dental school and sitting down with a student advisement counselor just prior to going out into the world.

Abel has included a course on business finance in his study of dentistry, while Cain has kept his head down working extra hours in the university lab. Both are straight-A students. Both have been actively recruited and asked to join a large group dental practice management company. However, Abel and Cain both desire to forge their own paths.

Abel informs the university counselor he would like to set up a business model that provides him with economic momentum. Abel recalls for the counselor a London street scene from Bleak House in which Charles Dickens describes mud as "accumulating at compound interest."

Thomas Climo, PhD, is a dental practice management consultant and a past professor of economics in England.

Thomas Climo, PhD, is a dental practice management consultant and a past professor of economics in England.

"This is an apt illustration of how I would like my practices to grow revenue," he tells the counselor.

Cain, on the other hand, likes the idea of leisure and independence and, other than the necessary multitasking that comes with owning a dental practice, he likes the peace of mind of knowing once he procures an existing set of loyal and oral hygiene-minded patients, he will be pretty much set for the remainder of his life.

Abel buys his first practice and produces a business plan consisting of the acquisition of one practice a year until such time that a 15% margin on net income against annual revenue is secured. Abel understands he will have to generate positive and growing earnings before interest, depreciation, and amortization (EBIDA) to achieve his goal of creating economic momentum. (The "T" from the usual EBITDA acronym is removed since Abel's practice is a limited liability company [LLC] and earns pass-through income for taxation purposes.)

Cain buys his first practice and begins his marketing and observatory work. He has no business plan beyond his plan to remunerate himself to the tune of approximately $150,000 to $200,000 per annum. His accountant will set up his chart of accounts to reflect this remuneration as bottom-line profit that passes through the LLC as income for taxation purposes.

How much risk is enough?

Abel and Cain have chosen their course of history. Let's lay it out so we can see how the risk-taking Dr. Abel contrasts the growth of his practices with the risk-averse solo practice of Dr. Cain. For illustration purposes, we adopt a 12-year period. This table will be helpful.

The first set of numbers shows the acquisition of 12 practices representing the manner Dr. Abel will grow his revenues; while the much shorter set of numbers below it with the heading "Solo practice" represents the expected outlook for Dr. Cain.

In their first year after graduation, Cain and Abel both buy a dental practice for $500,000. (We have to say "buy" because in every instance of a dental practice that begins with only linoleum flooring, the minimum expected cost in setting up this practice with at least two observatories and the necessary equipment, fixtures, and furnishings exceeds $1 million.)

Both doctors create gross collections in the first year of $1 million.

Dr. Cain has hired an accountant to do his books and a payroll company to pay his staff, but does all marketing and administrative chores himself. He pockets a handsome salary and drives $50,000 to the bottom line. He is so happy with these results he is content to repeat this sample year ad infinitum, or for the remainder of the 12 years of our illustration.

Dr. Abel has set up an independent management company to run his first practice, with instructions to grow the management company in direct correlation with the number of practices added. Obviously, existing management can handle one more acquisition, but after that there is a pro rata effect of adding staff and management expense as the number of practices grew. Dr. Abel pockets a less handsome salary than Dr. Cain, and, to pay for the management company, will drive net losses to his bottom line in the first five years of operations.

The turnaround point for Dr. Abel is in the seventh year when his net margin equals 5%, the same as Dr. Cain's. However, when Dr. Abel hits the 5% net margin, you will also see he has 10 times more EBIDA than Dr. Cain, $2.5 million contrasted with $250,000.

Gross collections are seven times greater for Dr. Abel by the seventh year. This means that, by the conventional manner of evaluating dental practices, Dr. Abel could sell his group practice for at least seven times more than Dr. Cain. By this time, Dr. Abel is on a better salary than that of Dr. Cain. Dr. Abel has more income, more upside, more value, and a healthier looking set of financial statements than Dr. Cain.

Repeatable net income

The true value of Dr. Abel's finance-driven methodology demonstrates itself on the acquisition of his 12th practice. He has more than 12 times the gross collections and 48 times the net income of Dr. Cain in this year. It is a pivotal year, as it launches what is termed in business finance as "repeatable net income."

Better, because he has professional management behind his repeatable net income, Dr. Abel's dental practices resemble all other value-added companies, independent of their industry. Dr. Abel has successfully taken the word "cottage" from a description of the dental industry. His group of practices falls into the mainstream of any well-run corporate entity.

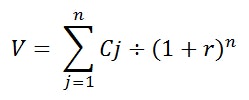

Armed with the findings from his study of business finance, Dr. Abel is able to use the company valuation formula therein to estimate the worth of his group of practices:

- V is the value of Dr. Abel's group of practices.

- j = 1 ... n is the number of years of expected investment -- here 12 years.

- C is the EBIDA or net income for a particular year j = 1 ... n, with the 12th year in a net repeatable form.1

- r is the cost of capital as expected to range over the term of the investment.

The only missing parameter for understanding the value of either $2.4 million of annual net income or $5 million of annual EBIDA is to match them against the cost of capital. Data for this are made available in the "useful data sets" from the Stern Business School of New York University.2 Although we could apply against the expected annual EBIDA or annual net income the dental industry cost of capital of 7.56%, we find it preferable to use the cost of capital for private equity investment, or 10.19%.3 When we do so, Dr. Abel's 12 practices yield a valuation in the range of $24 million to $49 million.4

Unfortunately, Dr. Cain is still running the operations himself, and, without professional management, he is hindered by the less-than-accurate appraisal methodology of practices of old which appears to value practices at about 75% of the prior year's gross collections, or $750,000. Dr. Cain is ensconced firmly in a cottage industry.

The good news

Twelve years after leaving graduate school, Dr. Abel has an annual net income of $2.4 million after paying himself a handsome salary and creating a valuation for his business in the $24 million to $49 million range. He also owns a proven dental practice management company. He is ripe for an investment by a private equity group and/or a large group practice management company.

Dr. Cain pays himself a handsome salary, but has a low annual net income of $50,000 with very little upside potential on the sale of his practice. If he prices his practice low enough, he will probably attract interest from similarly minded solo practitioners.

At a net margin of 20%, not only does Dr. Abel outperform Dr. Cain at 5%, he is also posting a rate of return that rivals the returns associated with large group dental practice management companies, many of which have practices numbering in the hundreds.

Dr. Abel has kept his identity while rewarding his dentistry efforts with the same kind of valuations we have come to expect only from large group dental practice management companies.

The good news is you can do it too.5

Thomas Climo is a past professor of economics in England and has a long tenure in America of consulting to both large group dental practice management companies and solo-owned dental practices in Arizona, California, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Nevada, and New York. He can be contacted at [email protected] or 702-578-2757.

1 When using EBIDA to replace net income, the presumption is we are measuring economic and not accounting profit. But any economic profit must include the cost of capital and the degradation over time of long-life assets. Cost of capital is dealt with in the classic valuation formula as stated above. However, to quote Warren Buffett: "Does management think the tooth fairy pays for capital expenditures?" Depreciation, while not exact in its accounting formulation, remains the most practical method available. In light of this, the valuation formula can suitably interchange EBIDA with net income and provide a range of valuation low to high.

2 https://people.stern.nyu.edu/adamodar/New_Home_Page/data.html

3 Josh Kosman documents the rush from private equity to provide funding for suitable dental practices in "Private Equity $inks Teeth into Dentistry," New York Post, August 27, 2010. Private equity cost of capital is a good opportunity cost or hurdle rate for quantifying the valuation of a company in the dental industry as it matches sales price against those most likely to buy.

4 $2.4 million ÷ 10.19% = $24 million and $5.0 million ÷ 10.19% = $49 million.

5 I am currently assisting in such a program for a solo practitioner in New England. By 2014, at six practices, the cross-over point that pays for the management company is reached and positive net margins start to appear pro forma. By 12 practices, a 15% net margin and repeatable net income of $1.8 million on $12 million of revenue are shown.

Thomas Climo, PhD, is a professor emeritus of accounting and finance at a major university in the U.K. He has published extensively about the importance of modern managerial and financial decision-making for dentistry. He is a consultant to corporate and solo practitioner dental practice management companies in the states of Arizona, California, Connecticut, Nevada, New Hampshire, New York, and Massachusetts. He can be reached by email at [email protected] or by telephone at 702-578-2757.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of DrBicuspid.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular idea, vendor, or organization.