Public health researchers and agencies have been estimating geographic access to dental care for decades; however, their approaches are often criticized as inadequate or inaccurate. A 2017 ADA Health Policy Institute (HPI) analysis on geographic access to dental care for publicly insured children is the latest of these methodologies to be critiqued.

Among other things, the HPI analysis estimated the percentage of publicly insured children who live within 15 minutes of a dentist who accepts insurance from Medicaid or the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP). However, the institute did not include provider capacity in its analysis, a serious flaw according to the authors of the new critique, published on August 7 in the Journal of Public Health Dentistry.

"The accuracy of various methods for estimating spatial access to dental care is more than just an academic concern," wrote the authors, Nicoleta Serban, PhD, from the Georgia Institute of Technology and Scott Tomar, DMD, MPH, from the University of Florida College of Dentistry. "The ADA HPI estimates may influence the decisions of state legislatures, which have control over Medicaid policy and regulation of health professionals."

The 2017 HPI analysis

“The ADA HPI estimates may influence the decisions of state legislatures.”

In 2017, the ADA Health Policy Institute released new data on geographic access to dental care for publicly insured children. The analysis was intended to improve on the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration's health professional shortage area data, which have their own shortcomings. The HPI analysis also attempted to explain why two states with roughly the same number of providers participating in Medicaid could have vastly different dental care usage rates.

For their analysis, the HPI researchers used Insure Kids Now (IKN) data, which were some of the best publicly available data for all 50 states plus the District of Columbia, the HPI noted. However, the IKN database does not include information on whether dentists actively participate in Medicaid or if they accept all insurance provisions.

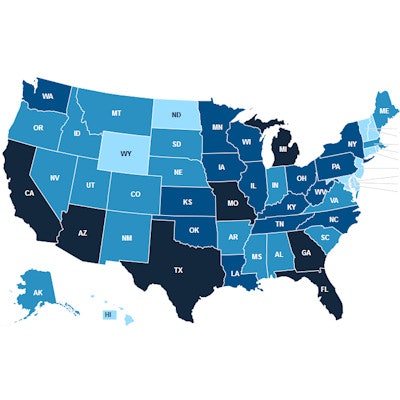

The HPI released data showing that the vast majority of publicly insured children within most states live within 15 minutes of a dentist who accepts Medicaid. The institute also included a state-by-state analysis and maps on the geographic distribution of Medicaid-enrolled providers per 500, 2,000, and more than 2,000 Medicaid-enrolled children.

Marko Vujicic, PhD. Image courtesy of the ADA.

Marko Vujicic, PhD. Image courtesy of the ADA."It is also important to note that HPI's analysis produced 11 statistics and four maps for every state," Marko Vujicic, PhD, vice president and chief economist of the ADA HPI, told DrBicuspid.com. "We did this because there is no empirically backed 'gold standard' or single definition of geographic access to dental care providers."

At the time of publication, the HPI team was very clear that its data could reveal some information, such as roughly where enrolled providers are and aren't located within a state relative to the Medicaid population. However, the institute also repeatedly emphasized the data could not reveal whether those dentists are actually seeing patients or how many patients providers are seeing.

"I want to recognize right up front this is far from perfect," Vujicic said in a 2017 webinar when the data were released. "We are counting dentists as Medicaid providers if they have enrolled to be Medicaid providers. They may not be seeing patients. They may not be seeing patients after 6 o'clock. They may not be seeing new patients. We don't have any way to access those types of information nationally for our analysis, and we're very, very clear about the shortcomings."

Real-world consequences

Despite the HPI's warnings, some policymakers used the 15-minute statistic to support the claim that their state has an adequate number of Medicaid providers, even if other, state-specific data suggested the opposite. For instance, the Florida Dental Association used the HPI data to assert that the state had adequate providers to support its Medicaid population, a claim that baffled Serban and Dr. Tomar.

Scott Tomar, DMD, DrPH.

Scott Tomar, DMD, DrPH.So Serban and Dr. Tomar conducted their own analysis using Florida's dental census data. While the HPI analysis found about 30% of dentists participated in Medicaid for children, Florida-specific data showed that number was actually around 15% and dropped 11% when focusing on providers who see at least 100 Medicaid-enrolled children.

"More accurate data sources and more rigorous modeling approaches suggest that the ADA HPI methodology substantially overestimated spatial access to dental care for children insured by Medicaid or CHIP," Serban and Dr. Tomar wrote. "The ADA HPI access estimates were derived using a simplistic methodology (2SFCA) that has been shown to have many limitations, generally overestimating spatial access."

Serban and Dr. Tomar also looked at Medicaid claims data available for 43 states and found that provider access fell far below the thresholds used in ADA's analysis. Only 22% of providers had a capacity of more than 500 children, they found, and capacity varied greatly between states.

"There are potentially major policy and practice implications to substantially overestimating spatial access to dental care, as appears to be the case with HPI's approach," they wrote. "State policymakers may conclude that advancing policy to improve access to dental care for publicly insured children is not needed in their jurisdiction."

Moving forward

It is important to note that the new analysis is not without its shortcomings either. Most notably, the Medicaid claims data were not available for all 50 states plus the District of Columbia, and few states conduct dental censuses.

Nevertheless, the new study adds to the overall body of scientific literature on how researchers and policymakers may better define and estimate geographic access to dental care, and Vujicic praised Serban and Dr. Tomar's analysis.

"HPI's geographic access analysis is a starting point for improving our understanding of the supply of Medicaid providers available to Medicaid beneficiaries," he said. "It is based on publicly available data, and we openly and very transparently recognize the shortcomings. We applaud these authors' efforts to build on our analysis and advance the policy discussion in Florida and Georgia."

Vujicic also noted that the HPI is currently working on more detailed state analyses, which do include claims data.

"The Health Policy Institute is currently collaborating with government agencies in several states on a much more refined analysis of access to and utilization of dental care services among publicly insured children and adults, based on detailed administrative and claims data, as well as innovative primary data we are helping to collect," he said. "We will continue to help advance this important area of health policy research, including collaborating with outside researchers, and welcome additional feedback on our work as it evolves."