The good news is more cancer patients are surviving than ever before.

The bad news is it creates new challenges for the medical community to provide adequate and appropriate aftercare and treat the many short- and long-term side effects of cancer treatment.

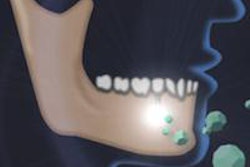

For example, chemotherapy and radiation often cause oral problems such as mucositis, xerostomia, oral and systemic infections, and accelerated caries development. But many dentists refuse to treat cancer patients with these conditions due to the increased risk of osteonecrosis from radiation treatment or bisphosphonate use.

Enter Ryan Lee, DDS, MPH, MHA, who is finishing a postgraduate clinical fellowship in dental oncology at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. He hopes to help solve the shortage of dentists with the training to treat the growing number of cancer patients who need specialized oral care.

Ryan Lee, DDS, is one of a handful of dentists specializing in dental oncology.

Ryan Lee, DDS, is one of a handful of dentists specializing in dental oncology.

Dr. Lee is one of two fellows in Sloan-Kettering's dental oncology fellowship program, which has been offering the specialty training for at least a decade.

"All along I've liked working on medically complex cases with dental needs, so cancer fit into that niche very well," he told DrBicuspid.com. "I've come to realize how much of a growing need it is and how little is available to meet that need," he explained.

Currently, only two cancer hospitals offer fellowship training programs for dental oncology: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

"Oncology training in the dental setting is a new and growing field, kind of a cottage industry," Dr. Lee said. "When I went to dental school, cancer instruction was just a couple of lectures, and we learned mostly about oral cancer. We didn't learn about the oral manifestations of systemic cancer that can be anywhere in the body."

In fact, most of his patients don't have oral cancers; most have breast or prostate cancer. And yet he sees hundreds of patients each month who present with cancer-related dental sequelae, including radiation-induced xerostomia, osteoradionecrosis, bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw, chemotherapy-related manifestations, oral (pre)cancerous lesions, and surgically resected jaws.

Dr. Lee also prescreens patients prior to bone marrow and stem cell transplants, head and neck radiation, and other cancer treatments.

"But we, as a dental profession, need to see these patients even when they're outside the hospital setting," he said. "The buzzword is oral systemic condition."

An emotional toll

Some of Dr. Lee's most difficult cases involve pediatric patients who have liquid tumors such as myeloma and often need chemotherapy and stem cell or bone marrow transplants.

"The effects of that are pretty severe in the mouth," he said. "A lot of the children are missing teeth, and their adult teeth never fully develop so managing them throughout the course of their growth is a big issue -- not only in clinical terms like chewing, eating, and smiling, but also the psychological impact."

Treating cancer-stricken youngsters takes an emotional toll. "There's nothing like seeing a bunch of kids with alopecia, and you know they're going through cancer treatment," Dr. Lee said. "It just breaks your heart."

“Oncology training in the dental setting is a new and growing field, kind of a cottage industry.”

— Ryan Lee, DDS, Memorial

Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

There are many physical challenges as well, he noted; for one, many patients must get a dental clearance before they start radiation therapy.

"When you get radiation to the jaw, it affects the blood vessels in such a way that you have nonhealing, so any dental extractions or oral surgery cannot be done after radiation to the mouth because of the risk of osteoradionecrosis," Dr. Lee explained. "So we see a lot of those folks."

Cancer patients also often need extensive oral surgery before they can be cleared for transplants.

"We often have patients that need 12 to 15 teeth extracted before they can go in for a transplant," Dr. Lee said. Although the protocol calls for allowing three to four weeks for proper healing, sometimes they can't wait due to the patient's deteriorating condition and the urgent need for the transplant, he explained.

And during cancer treatment, a patient's immunity is greatly diminished, which can result in abscesses and gingival inflammation, Dr. Lee said.

"You've got to manage these types of patients carefully, and these are the types of patients dentists on the outside really don't want to deal with," he noted.

Creative solutions

One of his most difficult cases involved a 29-year-old woman with fanconi anemia, an inherited blood disorder that leads to bone marrow failure. She subsequently developed squamous cell cancer in her mouth and has had multiple cycles of radiation, which puts her at a very high risk of osteoradionecrosis. She also has trismus (a contraction of the muscles of mastication), leaving her with limited ability to open her mouth because of the fibrosis, Dr. Lee explained.

"Because of her radiation history she has bursitis, and she's full of mouth sores," he said.

The woman is now missing a couple of front teeth and because of her fanconi anemia, she never developed adult teeth and now wants implants.

"Imagine performing oral surgery to place implants on someone who's had that much radiation, who cannot open her mouth," Dr. Lee said. "We can't even take impressions because we can't fit the tray into her mouth. That alone is an incredible challenge."

He was forced to come up with creative solutions, including making customized smaller trays and using unusual materials.

"We've actually used butter just to be able to put a small impression tray in her mouth," Dr. Lee said. "Having the tray in her mouth just hurts her so much because her gums are so inflamed."

He is now focusing on dentures so she can stabilize the woman's occlusion, but he must specifically measure how much radiation was given in the areas where the implants will be placed.

Fortunately, her illness is now in remission.

"She's an incredibly smart person with such a great outlook, and she encourages me when I'm having a long day," Dr. Lee said.

Influencing policymakers

Dr. Lee is encouraged by the work of Texas dentist Dennis Abbott, DDS, who specializes in oncology and has seen his practice grow quickly. Drs. Lee and Abbott met at a dental conference, and the two discussed the growing need for dentists who can treat cancer patients with specialized needs.

"It's such a small, relatively unknown field," Dr. Lee observed.

But Dr. Lee, who is working toward another doctorate in health policy, hopes to change that. In addition to becoming an academic-level dental oncologist, he would also like to practice part time treating the cancer-specific needs of patients.

"It would be nice to be able to influence policymakers and show them that dental oncology treatment is a medically necessary condition, that the effects on the mouth are severe," Dr. Lee said.