The discovery that a certain protein is overexpressed in patients with oral cancer may give new treatment hope to people suffering from forms of head and neck cancer, according to the University of Michigan School of Dentistry.

Researchers at the school found that when they inhibited the expression of that protein, called SIRT3 or Sirtuin-3, in oral cancer cells in a petri dish, the cells did not proliferate and more of them died.

Further, when researchers suppressed the protein in the cancer cells and combined that with radiation or chemotherapy treatment, the prohibitive effect on cancer cells was even greater, said lead study author Yvonne Kapila, DDS, PhD, an associate professor in the school's department of periodontics and oral medicine.

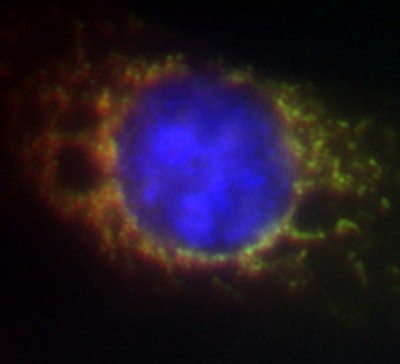

Oral squamous cell carcinoma expressing the protein SIRT3 is green, the nucleus is blue, and the mitochondria are red. Image courtesy of the University of Michigan School of Dentistry.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma expressing the protein SIRT3 is green, the nucleus is blue, and the mitochondria are red. Image courtesy of the University of Michigan School of Dentistry.

Mice that were injected with SIRT3-inhibited oral cancer cells had about a 75% reduction in tumors compared with the mice injected with regular oral cancer cells, said Dr. Kapila, whose research team began looking at the Sirtuin group of proteins because some studies suggest they are key regulators for cell integrity and survival.

"We thought that maybe cancer cells, because they are very crafty, may also use one of these proteins to their advantage to extend their own survival," Dr. Kapila said in a press release. "With oral cancer, often the problem is the difficulty of early detection, thus when diagnosed at a late stage, the cancer becomes very aggressive. If one can find a way to tailor treatments to those aggressive situations, obviously you have a far better case of survival."

Oral cancer survival rates haven't changed in decades, so there's a great desire in the scientific community to find more effective treatments, she added.

Oral cancer is the eighth most common cancer worldwide, and oral squamous cell carcinoma accounts for 90% of all malignancies. The five-year survival rate for patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma is 34% to 62.9%, according to the researchers.

Some research has shown that SIRT1 and SIRT3 proteins may suppress, rather than support, tumor growth, so it's important to remember that each case is different, Dr. Kapila said.

"If people do find that in breast cancer it's a suppressor and we go in and treat patients with an additional suppression of SIRT3, we may do more harm than good," Dr. Kapila said, stressing that the results are very preliminary. "This is very much still in the lab," she said. "We are nowhere near having any kind of treatment at this point."

The next step is to look at the SIRT3 in larger animals, then proceed to human trials.