A study published July 6 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America found a new type of inflammatory response to dental plaque buildup. It also may answer why some people are more prone than others to tooth loss and other inflammation-related complications.

When bacteria accumulate on tooth surfaces, the body creates inflammation to "tamp down" the buildup. Prior research found two major types of inflammation responses: a high, or strong response, and a low response.

But the group led by Shatha Bamashmous, PhD, of the University of Washington School of Dentistry in Seattle found there is also a third route, which they dubbed a "slow" inflammatory response. This type of response manifests as a delayed but strong inflammatory response to plaque buildup.

Additionally, the team found that patients with a low response also demonstrate a low inflammatory response to other types of inflammatory signals.

"This study has revealed a heterogeneity in the inflammatory response to bacterial accumulation that has not been described previously," study co-author Dr. Richard Darveau said in a statement released by the university.

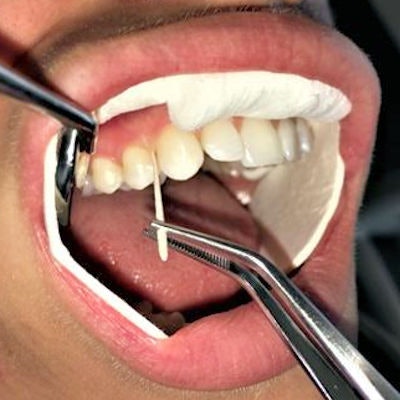

Researchers taking a gingival bacterial sample from a study subject. Image courtesy of Dr. Shatha Bamashmous, University of Washington School of Dentistry.

Researchers taking a gingival bacterial sample from a study subject. Image courtesy of Dr. Shatha Bamashmous, University of Washington School of Dentistry.Further, the authors learned the body can mount a response to plaque that protects tissue and bone by using white blood cells called neutrophils. In fact, the protective response of neutrophils, which were found in all three types of patients, appears to be critical to maintaining healthy homeostasis, as well as to save oral tissue and bone during inflammation.

"The idea of oral hygiene is to, in fact, recolonize the tooth surface with appropriate bacteria that participate with the host inflammatory response to keep unwanted bacteria out," Darveau stated.

The study included 21 generally healthy adults between the ages of 18 and 35. The authors monitored patients' inflammation levels for seven weeks, during which time the patients stopped their normal oral hygiene routine for three weeks to induce reversible inflammation.

The findings demonstrate that people exhibit a wide variety of inflammatory responses to bacterial buildup, the authors noted. They could help clinicians better identify people at higher risk of periodontitis, according to the statement. They can also shed light on how variations in patients' inflammatory response may be related to their risk for other bacterial-associated inflammatory conditions.