Switching to a diet focused on reducing inflammation may help those with periodontal disease, according to a small pilot study. Participants who reduced carbohydrates intake and increased omega-3 fatty acids consumption showed a significant improvement in periodontal health.

Since diet has been proved to help reduce inflammation, German researchers were curious how an anti-inflammatory diet would affect periodontal health. Their pilot study, published in BMC Oral Health (July 26, 2016), proved that similar diet-based studies for oral health are plausible.

"Examining the literature, several dietary recommendations for benefiting the health of periodontal tissues can be found, such as a reduction in carbohydrates, and an additional intake of omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin C, vitamin D, antioxidants, and fiber," the authors wrote. "Despite these very promising findings, there is a substantial lack of dietary-interventional studies in controlled randomized settings."

Importance of diet-based studies

Because so few randomized, controlled trials evaluating the relationship between an anti-inflammatory diet and periodontal health exist, lead author Dr. Johan Wölber, DDS, and University of Freiburg colleagues wanted to design a pilot study that could be repeated and built upon.

“There is a substantial lack of dietary-interventional studies in controlled randomized settings.”

They focused on reducing an excessive intake of carbohydrates, which have been shown to lead to chronic inflammatory disease. Dr. Wölber also advised participants to increase their intake of omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins C and D, and antioxidants.

The researchers sought out participants who were at least 18 years old, had gingivitis, and ate a carbohydrate-rich diet. They excluded those who smoked, used antibiotics, or had carbohydrate- or insulin-related diseases, such as diabetes.

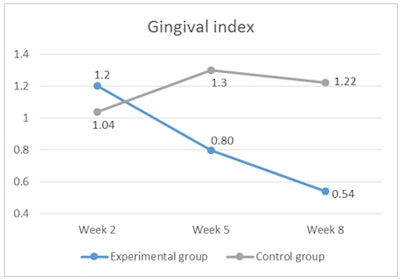

Dr. Wölber and colleagues ended up working with 15 participants: 10 who went on a low-carbohydrate, anti-inflammatory diet for six weeks, and five who continued with their typical diet for six weeks. The researchers chose six weeks as the time period to allow for a two-week adjustment period and four-week observation period.

With the exception of stopping the use of interdental cleaners, participants were advised not to change their oral health routines throughout the study period.

After the four observational weeks, the experimental group showed significantly reduced gingival and periodontal inflammation compared with the group who did not change their diet. Specifically, reducing carbohydrates led to a significant improvement in gingival index, bleeding on probing, and periodontal inflamed surface area. In addition, increasing omega-3 fatty acids and fibers improved plaque index.

These improvements in key periodontal health indicators occurred despite both control and experimental groups showing no change in plaque values. This led the authors to question the extent that plaque plays in the development of periodontal disease.

"The results raise several questions regarding the importance of dental plaque for the development of gingivitis/periodontitis and its impact on therapy," they wrote.

Need for more research

The study's most obvious drawback is its limited number of sample participants. However, it did succeed in its role as a pilot study, setting an example for researchers to follow. The findings are also an important reminder that a healthy diet is a key part of a successful oral health regimen.

The authors hope future researchers will study individual components of an anti-inflammatory diet to see if certain aspects have a more significant impact on reducing oral inflammation than others. They also would like other researchers to look at cholesterol, cytokines, and HbA1c.

"Within the limitations, the presented dietary pattern including a diet low in carbohydrates, but rich in omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins C and D, antioxidants, and fiber significantly reduced periodontal inflammation in humans," the authors concluded.