Scientists may have discovered a link between periodontal disease and neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease. A new study found chronic periodontal infection was associated with brain inflammation and neurodegeneration in mice.

Keiko Watanabe, DDS, PhD, and colleagues

Keiko Watanabe, DDS, PhD, and colleaguesThe researchers conducted their study to investigate why the periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis might be found in the brains of humans and mice with Alzheimer's disease. They published their findings in PLOS One (October 3, 2018).

"We use animal model systems to mimic chronic periodontitis -- i.e., long exposure to periodontal pathogens or gingival inflammation," lead study author Keiko Watanabe, DDS, PhD, a periodontology professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, told DrBicuspid.com. "So, we decided to further examine the brain for other possible alterations."

The mouth-mind connection

Dr. Watanabe focuses her research on the relationship between periodontitis and systemic diseases. She and her team previously discovered that chronic periodontitis could change glucose metabolism in the brain, and they wanted to investigate what other links may exist between the mouth and the mind.

To find out, Dr. Watanabe and colleagues used 20 wild-type mice. Half of the mice received an oral solution with P. gingivalis three days per week, while the other half received a saline solution. After 22 weeks, the researchers removed the mice's brains for evaluation.

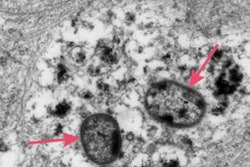

The brains of mice who received saline looked normal. But the brains of mice repeatedly exposed to P. gingivalis showed signs of degeneration, inflammation, and senile plaque that are typically characteristic of Alzheimer's disease in humans.

“Periodontitis is a chronic disease, and it takes a long time to develop.”

"One of the reasons that mice that received an oral application of a periodontal pathogen developed such significant neuropathology is due to the chronic exposure," Dr. Watanabe said. "Periodontitis is a chronic disease, and it takes a long time to develop."

Dr. Watanabe was surprised by the findings and admitted that she did not expect to discover such extensive brain changes after oral exposure to P. gingivalis. She was also surprised that her team discovered amyloid plaque, or senile plaque, since wild-type mice were previously thought to not develop it.

"This may be due to two factors," Dr. Watanabe said. "One, bacteria or its product may directly influence beta amyloid production. Two, prolonged exposure to periodontal pathogen resulted in a significant amount of neuroinflammation in the absence of aging."

More research still to come

While the research findings are noteworthy, the animal study was small with only 20 male mice, and the results may not be directly applicable to humans. However, more research into the mouth-mind link may come sooner rather than later as thousands of people have already accessed the study, and Dr. Watanabe and her team have begun a follow-up experiment.

"We are conducting research to determine if neuropathology that we observed is due to direct effects of periodontal pathogen/product or consequences of other factors triggered by oral application of a periodontal pathogen and the mechanism by which it occurs," she said.

Nevertheless, this was a landmark study that suggests mouth bacteria may influence distant organs, including the brain. It may even be possible that P. gingivalis plays a role in neurodegenerative diseases.

"Our results strongly suggest that chronic oral infection of [P. gingivalis] can be an initiator of the development of the neuropathology that is consistent with the characteristic of Alzheimer's disease in humans," the study authors concluded.