Porphyromonas gingivalis, the main pathogen that causes chronic periodontitis, can invade the brain, triggering symptoms characteristic of Alzheimer's disease, according to a study published online on May 5 in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease.

Results showed that P. gingivalis can invade and persist in mature human neurons expressing active proteases known as gingipains, further strengthening the tie between the bacteria and the degenerative brain disease. A better understanding of the connection could result in improved potential therapies for Alzheimer's disease (AD), the authors wrote.

"Infected neurons display signs of AD-like neuropathology including the accumulation of autophagic vacuoles and multivesicular bodies, cytoskeleton disruption, an increase in phosphotau/tau ratio, and synapse loss," wrote the group, led by Ursula Haditsch, PhD, a senior scientist at the biopharmaceutical company Cortexyme.

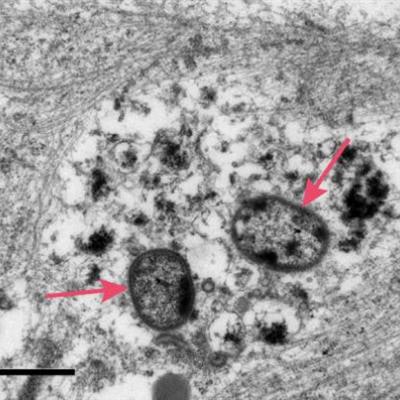

Arrows indicate the P. gingivalis bacteria after invading a neuron, causing damage to the cellular infrastructure and synapses. Image courtesy of Cortexyme.

Arrows indicate the P. gingivalis bacteria after invading a neuron, causing damage to the cellular infrastructure and synapses. Image courtesy of Cortexyme.Firming up the link

Imbalances in the bacteria and other microorganisms of the mouth cause periodontitis, which is the most common cause of tooth loss worldwide. P. gingivalis, a main driver of chronic periodontitis, uses gingipains to break down proteins for its primary source of energy.

Previous research has shown that gingipains were present in more than 90% of the postmortem brains of patients with Alzheimer's, and gingipains have long been studied for their potential role in the development of the disease. A study in animals also showed that P. gingivalis infection resulted in neurodegeneration and inflammation in the brain.

The current study, which was funded by Cortexyme, aimed to demonstrate intraneuronal P. gingivalis and gingipain expression in vitro after infecting neurons derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC). The researchers tested the effect of the bacteria on the neurons after 24, 48, and 72 hours.

The bacteria can infiltrate and persist in mature human neurons expressing active gingipains, and the neurons showed numerous signs of Alzheimer's disease 48 hours after they were infected with P. gingivalis, Haditsch and colleagues found.

The neurons showed infection-induced cell death, as well as degraded tau protein and increased tau phosphorylation, accumulated intraneuronal autophagic vacuoles and multivesicular bodies, synapse loss, and cytoskeleton disruption. Synapse loss causes sensory, motor, and cognitive impairments and is one of the earliest known indicators of Alzheimer's disease, according to the group.

Though no limitations were noted, the study was performed with a bacteria-to-cell ratio of 300. This ratio likely is much higher than what a neuron in the brain might encounter, and the resulting degenerative effects may be more pronounced and more toxic than what are encountered at physiological levels. Despite this, the neuropathological effects appear very comparable to an Alzheimer's disease brain, the authors wrote.

The key to new treatment

These results highlight the need to study the pathogen and its potential use in developing treatments for Alzheimer's, the authors wrote.

"Comparable features of neuronal degeneration combined with presence of gingipains are detected in AD brains, and we propose that human iPSC-derived neurons infected with P. gingivalis are a novel in vitro model to investigate the neuropathological mechanisms and treatment of AD," they concluded.