Bacteria and yeast are jointly responsible for early childhood caries, previous research suggests. Now a new study has isolated the surface molecules on yeast that interact with bacteria to form some biofilms, potentially leading to a novel strategy to fight this disease.

Researchers wanted to see if a particular enzyme was able to bind to certain proteins in the cell wall of the fungus Candida albicans, which is partially responsible for early childhood caries. They found that some C. albicans strains lacking certain genes were not able to form particular biofilms with the bacteria Streptococcus mutans. They published their findings in PLOS Pathogens (June 15, 2017).

"The results of our studies and others in this area may potentially lead to new therapeutic approaches that block the bacterial-fungal association associated with caries and other diseases by targeting precisely the interacting molecules between these two different kingdoms," senior study author Hyun (Michel) Koo, DDS, PhD, told DrBicuspid.com.

Dr. Koo is a professor in the department of orthodontics and divisions of pediatric dentistry and community oral health at the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine in Philadelphia.

Tale of 2 kingdoms

The current standard of care for early childhood caries includes the use of fluoride as preventive care, targeting bacteria with antimicrobials, and surgery when tooth decay is significant, the study authors noted.

“The results of our studies and others in this area may potentially lead to new therapeutic approaches.”

Bacteria such as S. mutans are frequent culprits in causing early childhood caries, although previous research by Dr. Koo and his colleagues suggests that some decay may be due to a team effort with C. albicans. This yeast is often found in the sticky pathogenic plaque biofilms of children with early childhood caries and heavy infection with S. mutans.

"This disease affects 23% of children in the United States and even more worldwide," Dr. Koo stated in a news release. "In addition to fluoride, we desperately need an agent that can target the disease-causing biofilms and in the case not only the bacterial component but possibly also the Candida."

C. albicans doesn't attach well to S. mutans unless it is in a sugar-rich environment. It is also not usually found in the plaque biofilms of children who do not have early childhood caries, according to previous research. Dr. Koo and his colleagues have previously found that C. albicans takes advantage of the exoenzyme GtfB produced by S. mutans to form a mostly intractable caries-associated biofilm in the presence of a sugar-rich environment. An exoenzyme is an enzyme that acts outside the cell that produces it.

In their current study, they tested the hypothesis that GtfB binds to mannoproteins in the cell wall of C. albicans. Using single-molecule atomic force microscopy, they studied the interactions between GtfB and various C. albicans, including some mutant variants.

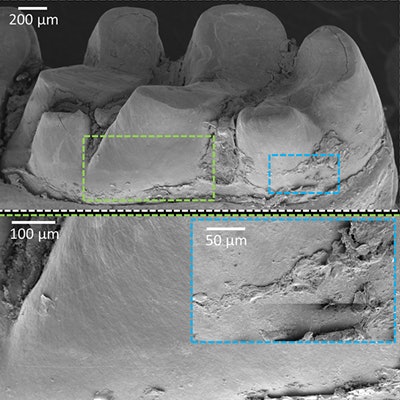

They found that GtfB binds strongly to mannans and C. albicans (wild type), but that the binding strength was significantly reduced in the C. albicans mutants (see images and table below).

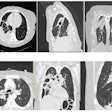

Scanning electron microscopy images of the in vivo plaque biofilms. Co-infected by (A) S. mutans and C. albicans wild type, (B) S. mutans and C. albicans on N-mannan outer chain, and (C) S. mutans and revertant of C. albicans on N-mannan outer chain. Boxes with red dotted lines show the numerous hyphal, or branching, form of C. albicans, while box with blue dotted line in (B) shows reduced amount of plaque without any C. albicans. Images courtesy of PLOS Pathogens.

Scanning electron microscopy images of the in vivo plaque biofilms. Co-infected by (A) S. mutans and C. albicans wild type, (B) S. mutans and C. albicans on N-mannan outer chain, and (C) S. mutans and revertant of C. albicans on N-mannan outer chain. Boxes with red dotted lines show the numerous hyphal, or branching, form of C. albicans, while box with blue dotted line in (B) shows reduced amount of plaque without any C. albicans. Images courtesy of PLOS Pathogens.The results indicate that mannoproteins on C. albicans surface mediate a strong and stable binding of the exoenzyme from S. mutans, the authors wrote.

| GtfB binding to C. albicans | |||

| GtfB binding force | GtfB amount (µg/mL) unbound | GtfB amount (µg/mL) bound | |

| C. albicans wild type | 1.59 ± 0.31 | 5.43 ± 2.67 | 18.12 ± 4.24 |

| Purified mannans | 1.12 ± 0.42 | 1.60 ± 1.67 | 13.33 ± 2.50 |

These results may suggest a different method of treating early childhood caries, according to Dr. Koo.

"Instead of just targeting bacteria to treat early childhood caries, we may also want to target the fungi," he stated. "Our data provide hints that you might be able to target the enzyme or cell wall of the fungi to disrupt the plaque biofilm formation."

Bacterial and fungal microorganisms

Dr. Koo noted, however, that additional longitudinal studies are needed.

"The take-home message is that both bacterial and fungal microorganisms may be associated with the development of early childhood caries," he wrote. "We are further investigating the mechanisms of yeast-bacteria interactions and possibility to develop new therapies to precisely target this interaction."