A healthy 46-year-old man was the longstanding patient of a general practice. The patient came to his dentist complaining of pain in an upper right premolar tooth, which had been endodontically treated and restored with a post, core, and crown 15 years before.

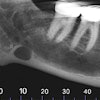

The dentist took a digital periapical image and noted what he believed was a radiolucency extending apically from the middle of the root. He advised the patient that he should see an oral surgeon to have an apicoectomy, which he advised was the best way to save the tooth.

The oral surgeon this dentist usually referred patients to was on vacation, so he called another local oral surgeon, to whom he sent the patient that same day. The dentist provided a referral letter, which simply stated "apico #4," and a printed paper copy of the radiograph.

The oral surgeon examined the patient and looked at the printout, which was somewhat hazy but adequately diagnostic, and was in general agreement with the dentist's assessment. The oral surgeon then explained to the patient that he would attempt to do the apicoectomy, but that he would not know definitively whether the procedure would be possible to save the tooth until he opened the area surgically to allow for a visual inspection.

The patient agreed and elected to go forward. The patient was provided with a written consent form for the procedure "exploratory surgery upper right," which included, among a number of potential risks, that "the tooth may be lost."

During the surgery, once the soft-tissue flap was elevated, the oral surgeon found a large vertical fracture, making the tooth unsalvageable. The oral surgeon stopped the procedure to explain the situation to the patient, who was sedated only with local anesthesia, and gave him the options of closing the area with the tooth untreated or extracting the tooth, with the hopes of placing an implant later. The patient voiced his desire to have the tooth extracted, as witnessed by a dental assistant, and the extraction was carried out uneventfully.

When the patient returned a week later for suture removal, the oral surgeon more thoroughly explored the implant and restoration prospects with this patient. The patient became visibly angry when he learned the costs involved and that his insurance plan would not cover those costs. He never returned to the oral surgeon, and the general dentist, to whom the patient did return, would not talk to the oral surgeon about the patient.

Legal stance

The patient filed a dental malpractice action in small-claims court against the oral surgeon, alleging that the tooth was extracted without his authority. He made no claim asserting that the extraction was unnecessary.

“Every aspect of documentation is ... critical.”

Because the oral surgeon's professional liability policy -- as do most, if not all, such policies -- provided for legal defense and indemnification, even in small-claims courts, he became our client. When we appeared with the oral surgeon for the trial, we argued that the case should be dismissed on both procedural and substantive grounds. Procedurally, the patient had no expert witness to support his claim, and, substantively, he signed a consent form for the surgery, which included as a risk that the tooth might be lost. The judge agreed with us on both bases and dismissed the case.

But the oral surgeon's happiness was short-lived, as he received a letter from the state's dental disciplinary authorities that the patient had filed a complaint against him for professional misconduct on the exact same ground.

Just as the oral surgeon's policy covered the small-claims action, it also covered our representation of him in the disciplinary action, as many, but not all, policies do. It is important to note that disciplinary authorities are not generally barred from investigating and acting even when cases have already been litigated and even when legal statutes of limitations periods have expired. It is also important to note that they are also not limited to look into only those issues raised by the complaining patient.

Procedural events

We responded to the authorities on behalf of our client. We explained the entire procedural past, providing the authorities with copies of all of our client's records for the patient. We also argued that the patient had been made fully aware of the risk that the tooth might not be salvageable before the procedure began, that he agreed verbally during the procedure, and they were free to interview the dental assistant if they chose.

After the investigation was concluded, the authorities agreed that informed consent had been appropriately obtained. However, they believed that the paper printout of the radiograph was not of sufficient quality to have served as the foundation for the surgery to have gone forward (which was never raised as a complaint by the patient); therefore, they intended to sanction the oral surgeon on this basis.

We obtained the affidavit of an oral surgeon who posited that the authority's focus was misplaced:

- The radiograph was of adequate quality.

- Given that fractures are so difficult to diagnose radiographically and that no radiograph could substitute for a direct eyes-on clinical assessment in a situation like this, the surgery would have been required anyway.

- Even if a fracture would have been able to seen on a better film, the patient would have undergone the exact same surgery in any event.

This affidavit led to a negotiation. Our goal was to avoid having an official censure of any type on the surgeon's record. In the end, the authorities agreed to waive a published sanction if the oral surgeon would take two hours of continuing dental education on the subject of radiographic diagnosis and with the understanding that subsequent complaints against this oral surgeon involving x-rays might lead to reopening this matter. The oral surgeon quickly completed the required coursework.

Issues raised

Two issues were raised during the legal process:

- The value of radiographs: Dentists are taught, from the very start of their educational careers, to take and evaluate radiographs, which are critical to the practice of the profession. There is an adage among some dentists, in response to dentists using x-rays that are less than diagnostic rather than overradiate patients, that if it is worth having an x-ray, it is worth having a good x-ray. Ultimately, it is the judgment of the dentist that guides determinations as to all patient issues, including radiograph quality and need.

- Malpractice versus professional discipline: When a patient sues in dental malpractice, regardless of the result or when in time in relation to the progress of the suit, that patient is not prevented from previously, simultaneously, or subsequently complaining to governmental authorities, even regarding the exact same issues. At the time of malpractice case settlements, despite solid language being inserted in the settlement documents of the patient agreeing to confidentiality, there is nothing to legally bar a subsequent disciplinary complaint.

Practice tips

- Quality of diagnostics: It is not uncommon for dentists who make specialist referrals to send their own radiographs, other diagnostic materials, or both to the specialist with the hope of preventing the patient from having to go through that process again. If the quality of those materials does not meet the standard otherwise deemed adequate by the specialist, it is incumbent upon them to make sure that determinations can be appropriately made and procedures can be appropriately performed, even if that means redoing the diagnostics and even in the face of patient (or referring dentist) protests. An argument by a specialist that previous radiographs, even though less than adequate, were used so as to prevent reradiating a patient will not carry the day, whether in court or before a disciplinary authority.

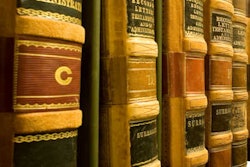

- Documentation is paramount: Every aspect of documentation -- chart entries, history taking, correspondence, billing records, and radiographs, to name but a few -- is not only important but critical. It is often a time-consuming process, but it will have been time very well spent in the event that a dentist's legal representatives need to provide a defense, whether in court or before a disciplinary agency.

William S. Spiegel, Esq., is a partner at the law firm Spiegel Leffler with offices in New York City, New Jersey, and Connecticut. He is a former assistant corporation counsel to the City of New York -- Medical Malpractice Division.

Marc R. Leffler, DDS, Esq., is also a partner at Spiegel Leffler. He received his dental degree from Columbia University, completed a residency in oral and maxillofacial surgery at New York University, and is a diplomate of the American Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery.

Disclaimer: Nothing contained in this column is intended as legal advice. Our practice is focused in the states of NY, NJ, and CT, and there are variations in rules of practice, evidence, and procedure among the states. This column scratches the surface on many legal issues that could call for a chapter unto themselves. Some of the facts and other case information have been changed to protect the privacy of actual parties.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of DrBicuspid.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular idea, vendor, or organization.