Many dentists would say that nothing is certain except death, taxes, and the need to get a clear view of impacted or diseased teeth before removal or surgery.

When it comes to looking below the gum line and deep into the mandibular canal, anything that helps you get a better view is essential. Two recent studies indicate that cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) is superior to conventional periapical x-rays for two types of preoperative visualization: inspecting impacted third molars prior to extraction, and viewing posterior maxillary teeth that have been referred for apical surgery.

Does this mean that more dentists -- including general dentists -- should be using CBCT in these two cases? It depends.

When it comes to preoperative diagnosis of posterior maxillary teeth referred for apical surgery, Dr. Karl Dula's opinion is crystal clear: "Absolutely not!"

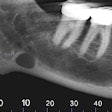

Dula, P.D., D.M.D., and a member of the department of oral surgery and stomatology at the University of Bern School of Dental Medicine in Switzerland, is a co-author of recent study that compared periapical radiography with CBCT for visualizing posterior maxillary teeth referred for apical surgery. The researchers found that CBCT yielded significantly better results in detecting lesions, including the expansion of lesions into the maxillary sinus or in roots in close proximity to the maxillary sinus floor (Journal of Endodontics, May 2008, Volume 34:5, pp. 557-562).

These findings do not mean that cone beam is always the best choice, however. "CBCT should only be used in cases where pain or other chronic sensation is reported and there is nothing to be seen in the periapical radiograph," Dr. Dula said. "If there is a lesion in the periapical radiograph, it is sufficient for diagnosis for apical surgery."

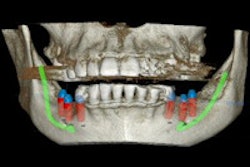

The lead author of the second study, which compared cone-beam volumetric imaging with radiographs for localizing the mandibular canal before removing impacted lower third molars, said his group's findings indicate that using CBCT is advantageous, but only under certain conditions (Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology, May 2008, Volume 105: 5, pp. 633-642).

"If the root tip is on or below the mandibular canal, the answer is yes," said Jörg Neugebauer, D.M.D., of the interdisciplinary outpatient department for oral surgery and implantology, department of craniomaxillofacial and plastic surgery, at the University of Cologne in Germany.

However, Dr. Neugebauer acknowledged that the diagnoses made either by CBCT or a panoramic radiograph and symmetrical PC cephalometric radiograph (PAN&PA) could not be confirmed by histology of the teeth because the scans were made "from real patients under clinical conditions."

Other observers are more enthusiastic about the role CBCT can play in preoperative diagnoses. Jeffrey H. Brooks, D.M.D., an oral surgeon with Central Arkansas Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Center in Little Rock, AR, and a fellow with the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, shares an i-CAT cone-beam scanner by Imaging Sciences with three other professionals primarily for implants. They perform 20 to 40 third-molar extractions per day. His opinion on the cone beam is succinct: "Use it."

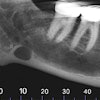

"Conventional panoramic scanners let you see whether or not the roots of the impacted third molar overlap the alveolar nerve, and you can see the superior-inferior position of the root in relation to the nerve," Dr. Brooks said. "But the medial-lateral position of the tooth in relation to the nerve is a mystery."

If the tooth is too close to the nerve and the nerve is bumped during extraction, numbness can result. "Prior to cone beam, I would always tell the patient, 'I can see that the nerve overlaps the root on the Panorex. However, I cannot tell how close the nerve is to the medial-lateral position, the horizontal position, or the cross-sectional position of the root.' The cross-sectional image cannot be obtained from a panoramic image."

According to Allan Farman, Ph.D., M.B.A., D.Sc., a professor of radiology and imaging science at the University of Louisville School of Dentistry, who edited Dr. Neugebauer's third-molar study, "Panoramic radiography is probably adequate in cases where the third molar is not superimposed or impinging on the canal. But I believe one needs to get a view of the third dimension every time, in situations where the canal is superimposed on or intimately related to the third molar on panoramic images."

According to Dr. Farman and Dr. Brooks, it's the difference between guessing (with the panoramic radiograph) and observing what is clearly shown (with the CBCT). Cone-beam technology makes it possible to take a cross-sectional view so you can see the medial-lateral as well as superior-inferior position of the tooth in relation to the nerve.

Dr. Brooks noted that, before cone beam became available, he would tell a patient, "We can see a change in the root canal, and we can see that the nerve is close to the root. If the tooth isn't painful, you may not want to risk a numb lip or paresthesia, and you can elect not to remove it."

Too much information?

But is knowing precisely how close the tooth is to the nerve causing some dentists to use bad judgment?

"The anecdotal evidence is that there are possibly dentists who are looking at cone-beam scans that show the third molar being 1 mm away from the nerve, and they think, 'I can take it out because it won't cause numbness.' They are being more aggressive in cases where they might have been more reluctant using a a panoramic radiograph," Dr. Brooks said.

On the other hand, cone beam gives additional control to both patient and practitioner. "From a medical-legal standpoint, it is a significant benefit," Dr. Brooks said. "If you have a symptomatic third molar that the patient cannot avoid taking out because it is going to cause an infection, a cone-beam scan can demonstrate that the third molar root is next to the canal or that the tooth root has formed around the nerve. You can image this with a CBCT, show it to the patient, and demonstrate that paresthesia will very likely result from the extraction. They can then sign the consent form to do the surgery, and if numbness does result, the practitioner is protected from being sued."

These studies provide further evidence that general dentists and other practitioners should be considering cone beam as an additional diagnostic tool. Still, as noted in previous articles, cone-beam technology takes time to pay for itself. Other pros and cons include:

|

Oral surgeons in particular should consider adding CBCT to their armamentarium, according to Dr. Farman.

"Third molars are not commonly removed by general dentists in the U.S.," he said. "Most cases are considered too complex and sent to an oral surgeon. This is a good reason for oral surgeons to have CBCT or to refer a patient for cone-beam CT. There are a number of systems and they are not all identical. Some reveal a fairly large volume of tissue, while others are more limited and just reproduce tissues that the dentist is familiar with. But the potential for damage to the mandibular canal, the possibility of loss of sensation to one side of the lower lip with likely drooling, and the consequent negative quality-of-life issues, mean that one should do whatever is possibly achievable to prevent those untoward effects from occurring. Now that we have CBCT and can look in three dimensions as opposed to 2D with a panoramic field-of-view, I would choose CBCT whenever there is doubt.."

Dr. Brooks, who is an oral surgeon, agrees. "If you do have a general dentist taking out a third molar, there is no question that there is a significant benefit to having cone beam in your office," he concluded.