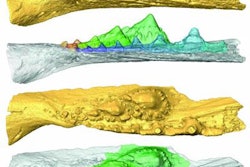

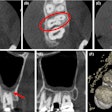

Researchers used 3D printing and computed tomography (CT) imaging to get a better understanding of a prehistoric shark and its unusual jaw, in a study published on November 17 in Communications Biology.

The symmoriiform shark Ferromirum oukherbouchi roamed the waters during the late Devonian Period. When F. oukherbouchi's mouth closed, its older and smaller teeth stood upright on the jaw, while the younger, larger teeth pointed toward its tongue, making them invisible. Sharks today have numerous rows of sharp teeth that continually regrow and can easily be seen even when their mouths are only slightly open.

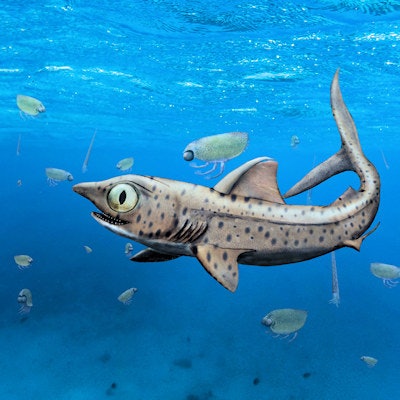

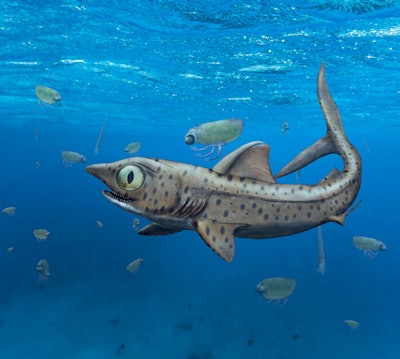

A reconstruction of the prehistoric shark with an unusual jaw. Image courtesy of Klug et al.

A reconstruction of the prehistoric shark with an unusual jaw. Image courtesy of Klug et al."Employing a large gape lined with generative sets of cladodont teeth, with those of the lower jaw rotating symmetrically inwards as the mouth snaps shut, would provide an effective means of capturing and retaining such seemingly abundant invertebrate prey," wrote the authors, led by Christian Klug, PhD, of the Paleontological Institute and Museum at the University of Zurich.

Little is known

The anatomy and functional morphology of chondrichthyans, such as sharks and rays, from the Paleozoic Era are poorly understood. This is because of their mostly cartilaginous skeletons, which are less likely to be preserved as fossils.

To get a better understanding, scientists examined the structure and function of the fish's peculiar jaw construction based on a 370-million-year-old chondrichthyan found in Morocco. They used CT scanning to reconstruct the jaw and print a 3D model, allowing them to simulate how the jaw moved. The findings ruled out the hypothesis that these fish had a complete gill between the mandibular and hyoid arches. Instead, the symmoriiform shark's jaw articulation is unique, the authors wrote.

In this shark, the jaw joint formed a hinge. However, the "rotational axis between primary and secondary articulations is offset relative to the cardinal axes of the cranium," they wrote. Basically, the sides of the lower jaw were not fused in the middle; the shark could drop both sides of its jaw down while automatically rotating both outward, according to a statement from the University of Zurich. This allowed the larger, sharper teeth to more easily snag prey and then pull it deeper inside the mouth, as the teeth rotated back inward with closure.

"The resultant eversion and inversion of the lower dentition presents a greater number of teeth to prey through the bite-cycle," the authors noted. "This suggests an increased functional and ecomorphological disparity among chondrichthyans preceding and surviving the end-Devonian extinctions."