Afflicted with a terrible toothache while at sea in the early 1800s, Richard Henry Dana Jr. wrote, "A sailor is always presumed to be well, and if he's sick, he's a poor dog."

Dana, who went on to author a best-selling book about his adventures on the high seas -- including a detailed account of the aforementioned toothache -- was born in Cambridge, MA, in 1815. His grandfather had been the first American minister to Russia and a chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court. His father was a distinguished professor.

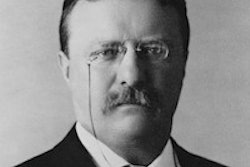

Richard Henry Dana Jr. (1815-1882)

Richard Henry Dana Jr. (1815-1882)

Dana matriculated at Harvard College in 1831. During his junior year (1834), he suffered an attack of measles which left his eyesight so weak that continuing his studies was impossible. Impatient with his slow convalescence, he decided to go on a sea voyage. Rather than going as a passenger, which he could have easily afforded, he opted to sign on as a common sailor on the two-masted brig Pilgrim, which was sailing to California. The Boston-based merchant ship, which had a crew of 10, was engaged in the California hide trade. The cow hides acquired in California were brought back to Boston and used in the leather industry (shoes, belts, outerwear, etc.).

Dana returned to Boston two years later (December 1836), re-entered Harvard, and graduated the following June. He then took up the study of law and opened offices in Boston in 1840. The following year Dana published his book, Two Years Before the Mast. The title referred to the practice of berthing common sailors before the ship's mast and officers and mates aft. The volume, a narrative description of his voyage, was drawn from a diary he had meticulously kept during the trip. It was an instant best seller, has been in continuous print ever since, and is today considered a classic.

'Little sympathy or attention'

The story, intended to publicize the hardships of common sailors of the time, also gives a detailed description of California in the mid-1830s when it was still a province of Mexico. The Pilgrim transited California waters from port to port, picking up hides produced at the various Catholic missions, which the Spanish had originally established.

The historian Mark Winthrop describes the book as an exposé of the "exhausting work of hide-curing" and the "cruelty on board ships." Dana himself opined, "a sick man finds little sympathy or attention, forward or aft." On his return trip aboard the merchantman Alert, he experienced this lack of sympathy firsthand.

As the ship began its transit of the perilous Strait of Magellan at the tip of South America, during a gale with "the decks covered with snow and a constant driving sleet," Dana wrote, "I had been troubled for several days with a slight toothache." Working outside in the ship's rigging in wet clothes in winds that nearly blew him off the mast and "ropes so stiff with ice" they were nearly impossible to bend, he recounted his ordeal. The cold weather and "wetting and freezing" were not "the best thing in the world" for the toothache, he observed.

“I never felt the curse of sickness so keenly in my life.”

— Richard Henry Dana Jr., Two Years

Before the Mast

As the pain increased, he sought out the chief mate who was in charge of the "medicine chest." But the chest was nearly empty from the long voyage. There was only a "few drops of laudanum left." Laudanum was a widely used opiate drug at the time, and the mate insisted it must be saved for more severe emergencies.

The Alert was also a temperance ship, which meant no pain-relieving alcoholic beverages such as rum, brandy, or whiskey were allowed on board. He was told "to bear the pain as well as he could." Aspirin and other common pain relievers we know today simply didn't exist at the time.

Dana was sent back outside in the gale-force winds. After several more hours, he was finally sent below. "The next four hours below were but little relief to me, for I lay awake in my berth the whole time, from the pain in my face," he wrote. He was unable to sleep, and after four hours below deck, he once again was beckoned topside again to rerig the ship.

Exhausted from the pain, he "had no sleep for forty-eight hours" and his face "for the want of rest, together with constant wet and cold, had increased the swelling." It was, he wrote, "nearly twice as large as two, and I found it impossible to get my mouth open wide enough to eat." The steward asked the captain for permission to boil rice for him. The request was rebuffed with a loud "No, damn you! Tell him to eat salt junk and hard bread, like the rest of them." Regardless, the steward smuggled a pan of rice into the galley for the cook to make for him. The steward "was a man well as a sailor," he thankfully recounted.

Again he was forced to perform his top-deck duties, doing them as well as he could. He could not desert his post as they entered an iceberg field. A heavy wind with hail and sleet together with fog was "so thick that we could not see the ice, with which we were surrounded." The sailors were forced to climb the rigging and "take in sail."

15 long and painful days

For two days the crew fought the seas for survival, and "the wet and cold had brought my face into such a state I could neither eat nor sleep," Dana wrote. He was finally ordered below and told to stay in his berth until the swelling receded. The cook was ordered to make him a poultice.

Dana laid there for 24 hours, "half asleep and half awake, stupid from the dull pain." Finally, the pain receded, and he "had a long sleep." It "brought me back to my proper state," he wrote. Yet his face was still "swollen and tender," and he stayed another three days in his berth recuperating.

By the end of the third day, all hands were ordered aloft -- more snow, rain, winds, fog, and "ice too thick to run." The captain told the men "that not a man was to leave the deck that night." "No one could tell whether she would be a ship the next morning." When he heard the alarming state of weather, Dana put on his clothes "to stand with the rest" of the hands. But the chief mate came below and "looking at my face, ordered me back to my berth," he wrote.

Dana spent a miserable night. "I never felt the curse of sickness so keenly in my life," he noted. The wind blew for two more days while he remained in his berth, tortured by "being perfectly useless." He had hardly eaten for nearly a week except a little rice. "I was as weak as an infant," he wrote. There he lay in the pale light of the single oil lamp "swinging to and fro from the beam ... the water, dropping from the beams ... and running down the sides ... so wet and dark and cheerless."

After six days below, he was finally able to resume his duties. He soon got his "mouth opened wide enough to take in a piece of salt beef and hard bread." He was finally "all right again." His toothache-induced misery had lasted 15 days.

Later in life, Dana became a well-known advocate for the oppressed and downtrodden, specializing in maritime law and a spokesman for sailors' rights. An abolitionist, he was a fervent activist for fugitive slave rights prior to the Civil War. During the Civil War, he served as a U.S. attorney and at war's end served as part of the legal team during the trial of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. He also served in the Massachusetts Legislature.

In 1882, Dana died of influenza in Rome, where he is buried.

Daniel Demers is a semiretired businessman whose hobby is researching and writing about 19th and 20th century historical events and personalities. He holds a bachelor's degree in history from George Washington University and a master's degree in business from Chapman University. You can review Dan's other published works at www.danieldemers.com.