Does the human body stop growing once we reach our late teens or early 20s, as most of us assume?

Recent studies indicate that soft-tissue and skeletal patterns in the nose, lips, and ears grow continuously throughout our lives. In fact, the actual maturation process of longitudinal soft tissue continues from 18 to 42 years of age, according to David Sarver, D.M.D., M.S., a Birmingham, Ala., orthodontist and adjunct professor at the University of North Carolina.

Dr. Sarver told an audience at the California Dental Association (CDA) spring meeting in Anaheim, Calif., last week that the dental team can learn from quantitative studies of facial and skeletal aging.

Sarver also discussed the role the nose, eyes, chin, complexion, and proportionality play in our perceptions of beauty and how these changes can affect our teeth -- as well as our overall appearance as we age.

For example, in women, maxillary lip length and thickness both go through a rapid growth phase between the ages of 10 and 16, but they begin to thin after that. At the same time, however, mandibular lip thickness continues to grow into the 20s and beyond, not thinning in the same way the upper lip does.

"Soft-tissue changes are inevitable, and as orthodontists and dentists we have to take this into consideration," Dr. Sarver said. "Decisions we make on young children affect how they look for the rest of their lives. When you look at the 'ideal smile' and the 'ideal face,' it's always a 25-year-old woman. But if [I'm] treating a 12-year-old girl I want her to look 14 when I'm done, not 25. Systematic evaluation of these criteria will lead you to the treatment plan."

He used several case studies from his own practice to illustrate this point, starting with an 11-year-old girl he first started treating (and photographing) in the mid-1980s.

She presented with blocked arches and overcrowding, so his first objective was to decrowd the arches. Prevailing wisdom at the time said this should be done by extracting the premolars. But there were additional issues to consider, Dr. Sarver said; her deep bite needed to be improved, which meant moving the incisors and extruding the posterior teeth -- a procedure that would also increase facial height over time, another desirable feature in terms of our perceptions of beauty.

In the long run, he was able to improve her mandibular projection and lip support and increase her vermilion display, which led to a very positive outcome, Dr. Sarver added.

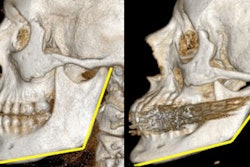

Throughout his talk, Dr. Sarver used "morphing" -- the layering of images taken over time and strung together into a movie of sorts -- to demonstrate how each patient's face changed over 20 years and how the treatment choices he had made early on played out, both in the mouth and the face. The effect was dramatic.

In fact, Dr. Sarver believes that facial planning and morphing may be the next important avenue of teaching for patients considering oral surgery and related aesthetic and corrective procedures. He also emphasized the importance of these techniques in improving interdisciplinary planning and producing optimum cosmetic and functional treatment results.

"In plastic surgery, the dentist needs to be part of the treatment and planning team," Dr. Sarver said. "Issues such as maturing lips, thinning and elongation of the upper lip, and nasal growth should all be part of the dental treatment plan."