Update on October 21 -- The following story is based on an article that has since been withdrawn from the Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery.

The journal article this story is based on has been withdrawn.

Elsevier, the publisher behind the Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, states article withdrawal is reserved for journal articles that have not yet been formally published and sometimes contain errors. In the new PDF, the journal article states it has been withdrawn at the request of the editor and publisher, and that the publisher "regrets that an error occurred which led to the premature publication of this paper."

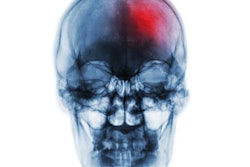

Oral and maxillofacial surgeons should monitor patients at moderate risk for infective endocarditis (IE) for four months after undergoing invasive dental procedures, according to a perspective published on October 13 in the Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery.

Monitoring for several months is being recommended based on a study published in August in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. The U.S. study, which included 8 million patients, revealed a notable link between invasive dental procedures, especially extractions and surgeries, and subsequent infective endocarditis in high- and moderate-risk patients.

"These findings, specifically the development of IE encountered by patients with a cardiac condition deemed by the AHA (American Heart Association) as of only 'moderate risk' cannot be ignored by members of our profession," wrote the authors, led by Dr. Arthur Friedlander, a professor in residence at the University of California, Los Angeles.

For more than 50 years, clinicians have debated the association between the performance of invasive dental procedures and the subsequent development of infective endocarditis. Part of the problem is the absence of randomized control trials on the subject. In 2007, the AHA limited its antibiotic prophylaxis (AP) recommendations, calling some patients with a few heart abnormalities, including prosthetic cardiac valves, "high risk" and in need of medication.

The August study sheds new light on the matter. The lengthy monitoring period is recommended because the study revealed that 831 patients developed endocarditis following invasive dental procedures. However, the AHA classified these individuals as "moderate risk" and not needing antibiotic prophylaxis. The moderate-risk patients had less complicated symptoms of endocarditis and were not diagnosed with the heart infection until about 120 days after they had tooth extractions, the authors wrote.

Additionally, oral surgeons should be aware that the study showed that preventive antibiotics provided a significant reduction (odds ratio, 0.34; 95% confidence interval, 0.14-0.88; p = 0.025) in the incidence of endocarditis, they wrote.

Nevertheless, "we suggest that until the AHA broadens its AP recommendation that maxillofacial surgeons adhering to the current AHA guidelines, in concert with the patient's primary care physician, monitor over a 4 month period of time, the post-operative course of 'moderate risk' patients for signs of IE," Friedlander and colleagues wrote.