When they were first introduced, dental implants were an inconsistent and unproven treatment option. But that did not deter Paul Schnitman, DDS, MSD, from learning everything he could about them as a young dentist.

Implant pioneer Dr. Paul Schnitman.

Implant pioneer Dr. Paul Schnitman.

Still, it took an inquisitive patient for him to place his first screw-type implants. In 1983, Elizabeth Scotland sought out Dr. Schnitman after learning about the new osseointegrated dental implant and became his patient.

"Basically, she came to me," Dr. Schnitman said during an interview with DrBicuspid.com. "After treating her case and becoming confident and then treating another, my reaction to her and watching her gave me confidence that these implants can really be for a lifetime."

Before her surgery, Scotland -- who is now 87 -- had a lower dental plate that was uncomfortable and ill-fitting.

"The bridge would come out with her teeth in them," Dr. Schnitman explained. "If you can picture a patient's bridge going around a jaw with 12 teeth in and a few roots sticking out of it. Those roots sat in loose holes in her gums. She was able to manage."

But Scotland knew there must be something better, and in 1983 she heard about the new osseointegrated dental implant that was available at a U.S. training center established by Dr. Schnitman at Harvard University.

Elizabeth Scotland's implants today. Image courtesy of Dr. Paul Schnitman.

Elizabeth Scotland's implants today. Image courtesy of Dr. Paul Schnitman.

She went to see him, eager to see if the implants would work for her. Ultimately, he replaced her lower dental plate with five lower implants.

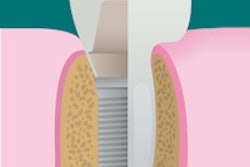

"Elizabeth Scotland's implants were done in a standard two-stage fashion," Dr. Schnitman said. "We put them in, buried them beneath the gum, waited three and a half to four months, uncovered them and put extensions on them. Then we added the teeth."

Thirty years later, "they're working perfectly; they look like the day we put them in. They gave her her life back," Dr. Schnitman said.

Researcher, practitioner

Dr. Schnitman placed his first implant in 1971.

"Implants in those days were frames that sat on the bone or blade-type implants," he explained. "The problem was that we would put the bridge right on the implant, and many times the implant would become loose. Now we know why that is."

The challenges back then included high-speed drills that would burn the bone, which would subsequently die back. In addition, operating room techniques weren't being employed, and dentists were putting loads on the implants right away.

“They look like the day we put them in.”

"So many of those implants failed and gave the implant field a bad name," he said.

Meanwhile, orthopedic surgeon Per-Ingvar Brånemark was applying his knowledge to dental implantology and researching a technique of putting a screw in the bone and burying it. But no one wanted to listen to the Brånemark approach because it was too complicated, according to Dr. Schnitman. Still, he was intrigued.

While completing an implant training program in the Brookdale Medical Center in Brooklyn, NY, he noticed that a great deal of the blade implants that they were placing became infected. That led to a research fellowship at Harvard and the creation of the National Institutes of Health-sponsored Consensus Development Conference in 1978 with the goal of "trying to bring some order to this field," Dr. Schnitman explained.

"We brought together 50 of the main academic and research leaders in the country and discussed implants, and came out with an acceptable survival rate of 75% success for at least five years," he said. "That in and of itself wasn't that good, but at least it was a start and gave us some guidelines."

He continued to study the loading of implants and to perform clinical trials. Then Harvard was among the 20 universities selected to become centers of the Brånemark approach.

"They brought us up to Toronto to observe Brånemark's patents and treatment," Dr. Schnitman recalled. "I was so impressed that when I went back to Boston, we treated this first patient (Elizabeth Scotland) with the Brånemark implant. That was one that I couldn't have treated in another way, so that Brånemark implant was pretty ideal for her."

Dr. Schnitman currently practices in Wellesley Hills, MA, and teaches implant treatment planning, surgery, and restoration to advanced graduate periodontal and prosthodontics residents at the Harvard School of Dental Medicine. He is the recipient of Harvard's Distinguished Faculty Award and the American Academy of Implant Dentistry's highest awards: the Aaron Gershkoff Memorial Award and the Isaih Lew Memorial Research Award.