Dentistry is sounding the alarm about early childhood caries (ECC) as data roll in about its long-term impact on oral health. Now a new study has the potential to give dentists another tool to help parents understand how their own oral health affects that of their very young children.

The researchers have shed more light on the relationship between the oral health of mothers and their children in a study published in the Journal of Dental Research (March 2014, Vol. 93:3, pp. 238-244). The data could be a piece of the solution that will break "an intergenerational chain of oral health disadvantage," wrote the researchers from the University of California, San Francisco; the University of California, Los Angeles School of Dentistry; and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Dentistry.

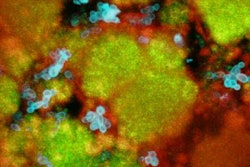

The intergenerational relationship that exists between the oral health of parents and children has long been established. More recently, researchers have examined the connection between the bacterial makeup of a parent's mouth and their children's. Studies in this area have yielded associations between higher levels of salivary mutans streptococci (MS) in mothers and their children, the researchers noted. In their own study, they hypothesized that higher maternal levels of MS and lactobacilli (LB) would be associated with an increased presence of caries in their children.

“Higher maternal salivary bacterial challenges [were] associated with child caries.”

The researchers calculated the odds a child will develop ECC based on the oral health of the mother and found striking results. "This study is the largest prospective longitudinal investigation showing that maternal MS and LB predicted not only oral infection among children, but also a meaningful increase in caries incidence," they reported. The data could help clinicians target the parents of young patients that are most likely to suffer from ECC and give them guidance about how to prevent caries from becoming a significant problem.

The prospective observational cohort included low-income Hispanic women who were registered patients at a health center near the U.S.-Mexico border. The women, who lived in a community without fluoridated water, were in their second trimester of pregnancy, between the ages of 18 and 33, and had a stable address.

They included 243 mother-child pairs for a 36-month child dental assessment, the researchers explained. Each pair returned for questionnaires, dental assessments, and saliva collection at four, nine, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months after the child was born. Radiography was not used to assess caries to limit radiation exposure.

Mothers gave a saliva sample before their child was born. If the mothers had one or more decayed teeth at all of their visits, they were rated as having persistent untreated decay. The researchers also used the Decayed, Missing, or Filled Teeth (DMFT) index when recording the mothers' situation and noted any restored primary teeth among their children.

Of the mothers, 100% had a caries experience, and 34% of their children had caries at 36 months, while 31% had untreated decay. In addition, the researchers confirmed the presence of MS and LB in 53% and 16% of these children, respectively. Mothers' whose children had caries also had higher bacterial levels of MS and LB, while children without caries were linked with having lower bacterial levels.

In particular, the children of mothers with elevated levels of MS averaged from baseline to 24 months faced an increased likelihood of being MS-positive after 36 months (63% versus 43%, p < 0.01). However, they did not find the same link with LB.

"Here, we demonstrated that, when adjusted for numerous factors, higher maternal salivary bacterial challenges was prospectively, longitudinally associated with child caries in a low-income Hispanic cohort," the researchers explained. After applying sociodemographic, feeding and care, and maternal dental status variables, the association estimates were the same.

In the researchers' opinion, maternal contacts, such as breast-feeding or sharing utensils, had more of an effect on the likelihood of child caries than "broader potentials sources of infection," such as attending daycare or the presence of siblings.

The study findings could contribute to an overall caries management strategy. "Broadly implemented maternal-child health initiatives might contribute meaningful reductions in oral health disparities by helping to break an intergenerational chain of oral health disadvantage," the researchers concluded.