Scientists have discovered a small area in the brains of mice that dampens their sense of pain, which could eventually lead to new pain management treatments for humans, according to a study published on May 18 in Nature Neuroscience.

The area that turns off pain was found in the central amygdala, and general anesthesia activates a specific subset of inhibitory neurons in this part of the brain. This was a surprising discovery because the amygdala is known for playing an important role in emotions and behaviors and for how it processes fear, such as triggering the fight-or-flight response, according to the authors.

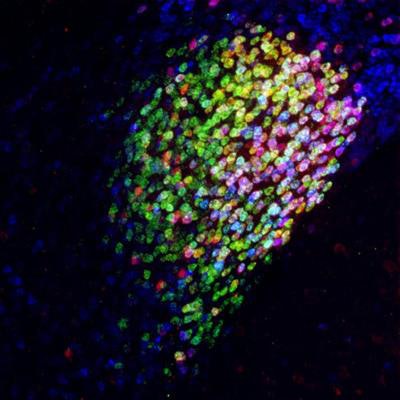

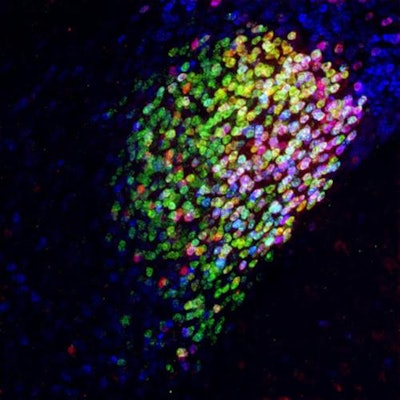

Neuron cells in the central amygdala in the brain of a mouse. Red, magenta, and yellow cells are part of a collection of neurons activated by general anesthesia that has strong pain-suppression abilities. Image courtesy of Fan Wang Lab - Duke University Medical Center.

Neuron cells in the central amygdala in the brain of a mouse. Red, magenta, and yellow cells are part of a collection of neurons activated by general anesthesia that has strong pain-suppression abilities. Image courtesy of Fan Wang Lab - Duke University Medical Center."Our study points to CeAGA [central amygdala neurons activated by general anesthesia] as a potential powerful therapeutic target for alleviating chronic pain," wrote the authors, led by Thuy Hua, PhD, of the department of neurobiology at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC.

Dentists prescribe 12% of all opioid prescriptions, making them the second-highest prescriber behind family doctors. Though the ADA and others recommend nonopioid analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to manage dental pain, dentists frequently prescribe opioids despite them being highly addictive and commonly abused. Researchers continue to search for alternatives.

General anesthesia can produce a loss of pain independent of a loss of consciousness, though why this occurs is unclear. Hua and colleagues hypothesized that general anesthesia suppresses pain at least in part by activating supraspinal analgesic circuits.

In the study, mice were given a mild pain stimulus, allowing the researchers to map pain-activated brain regions. CeAGA sent inhibitory input to at least 16 brain centers that process the sensory or emotional aspects of pain, they found.

Hua and colleagues also utilized optogenetics, a technology that uses light to activate a small population of cells in the brain. As soon as the light activated the CeAGA neurons in the mice, the animals stopped self-caring behaviors such as paw licking or face wiping that they exhibit when they feel uncomfortable. When the neurons were no longer activated, the mice responded as if they had been struck by something intense or that pain had returned.

Though this research shows potential for helping patients better manage pain, two things remain unclear. It is not known how general anesthetics induce transient or sustained activation of CeAGA neurons or whether persistently activating CeAGA neurons will be nonaddictive, the authors noted.

Therefore, further research is needed. Future studies should focus on identifying small molecular compounds that can specifically activate the neurons without the sedative effects of general anesthesia.

"Nevertheless, our work raises the exciting possibility of harnessing the power of this endogenous analgesic system to relieve chronic pain," they wrote.