Researchers have created a mobile application that monitors patients during their daily routine. The prototype may one day help clinicians diagnosis and monitor bruxism, temporomandibular disorder (TMD), and other jaw-related disorders outside of the clinic.

Mauro Farella, DDS, PhD.

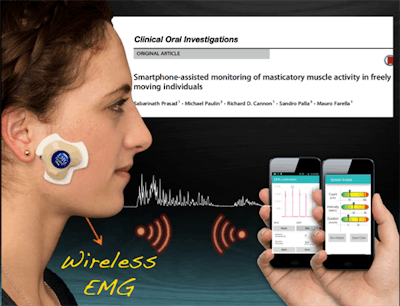

Mauro Farella, DDS, PhD.The prototype consists of a smartphone application and a small, wireless electromyographic (EMG) device that patients wear on their jaws. The system was created by an international team of researchers, who detailed their development process and pilot study findings in Clinical Oral Investigations (January 4, 2019).

"New, wearable devices similar to this one will become more and more popular in dentistry, both for research and clinical purposes," senior study author Mauro Farella, DDS, PhD, told DrBicuspid.com. "They can be used not only to monitor jaw function and eating behavior but also to detect awake and sleep bruxism, whose diagnosis can be particularly challenging."

Dr. Farella, the creator of the prototype, currently leads the orthodontics department at the University of Otago's dental school in Dunedin, New Zealand.

Seamlessly tracking muscle activity

Researchers and clinicians use surface EMG to track contractions of the masticatory muscle, helping them to diagnosis and monitor a variety of jaw disorders. However, current data collection is limited to large, stationary machines at laboratories and hospitals, or portable machines that include annoying wires or obtrusive receivers.

“New, wearable devices similar to this one will become more and more popular in dentistry.”

Because of these limitations, it can be challenging for clinicians to monitor the daily activities of patients with jaw muscle disorders. Therefore, Dr. Farella sought to develop an unobtrusive alternative.

"Some nonfunctional activities ... can occur repetitively across the day and have a cumulative effect to overload the jaw muscles and the temporomandibular joints," he said. "Nowadays, there is very limited information on jaw muscle activity as it naturally occurs during the day and when a physiological load can become pathological."

His solution for obtaining that data is a 1.1 x 1.4-inch wireless EMG machine. The nodular device sits at the masseter muscle and detects contraction activity. It is powered by a lithium-ion battery and weighs about the same as a quarter.

The wearable EMG syncs with a smartphone application that automatically records, calibrates, and visualizes muscle activity. The app also prompts users to enter relevant data, such as when they're eating, drinking, or sleeping.

"The wireless device we have developed is interfaced with a smartphone for logging data and simultaneously provides users with a real-time graphical representation of their muscle activity," the authors wrote in their paper. "This is advantageous, particularly in the light of research demonstrating the effectiveness of EMG biofeedback and/or cognitive behavioral therapy in reducing awake bruxism."

A new prototype wirelessly monitors jaw muscle contractions. Image courtesy of Dr. Mauro Farella.

A new prototype wirelessly monitors jaw muscle contractions. Image courtesy of Dr. Mauro Farella.Sleek device, big results

Dr. Farella and colleagues tested their sleek, wireless prototype against a conventional, wired system (Quad Bio Amp, ADInstruments). Their small study consisted of 12 healthy participants with no history of orofacial pain or headaches within the past month.

During a lab-based session, a trained researcher conducted EMG tests using software that guided participants through various muscle-related tasks, including chewing gum and biting on an aligner tray. The tests were done simultaneously with both the wireless prototype and the traditional system.

The researchers observed very similar EMG results for the prototype and the traditional machine. Both systems detected about 13 contraction episodes for all participants, and the results were significantly correlated. The prototype, however, struggled during some tests, such as smiling tasks and recognizing when teeth were in slight contact.

"Minor differences in the amplitude of muscle contraction episodes detected by the two types of equipment could possibly be explained by slight differences in the amplification and preprocessing of EMG signals," the authors wrote. "However, it must be emphasized that the differences in amplitudes were small and certainly not clinically relevant, and they did not influence the detection of individual contraction episodes."

Improvements still needed

Despite the study participants not having jaw disorders, the researchers found some patients exhibited high scores of atypical oral behaviors during long-term use. They noted that future studies will need to parse what long-term, daytime jaw activity is normal and what is not, a problem Dr. Farella and his team already are trying to solve.

The team currently is investigating long-term jaw muscle activity of patients with TMD pain, but they're also using the prototype to study children with eating disorders and stroke patients with dysphagia. Dr. Farella's goal is to make the next version of the device even slimmer and easier to use.

"We need normative data from a large sample of patients and controls to identify the boundaries between what can be considered a normal or an abnormal pattern of jaw contractions," Dr. Farella said. "The device must become smaller and cheaper."