A new study published in the December edition of Health Affairs analyzed access to dental care for Medicare beneficiaries, and the findings don't look good. Only about 10% of older U.S. adults have dental insurance, and, of those who do, they still pay half of all their dental costs out of pocket.

The researchers looked at Medicare data to see how seniors with different income levels and types of insurance access dental care. They attributed the overall lack of coverage and high percentage of out-of-pocket spending to larger policy trends, including the exclusion of dental care in Medicare and the changing of insurance benefits for retirees.

"Despite the wealth of evidence that oral health is related to physical health, Medicare explicitly excludes dental care from coverage, leaving beneficiaries at risk for tooth decay and periodontal disease and exposed to high out-of-pocket spending," wrote the study authors, led by Amber Willink, PhD (Health Affairs, December 2016, Vol. 35:12, pp. 2241-2248). "The fact that beneficiaries are forgoing dental care and are exposed to significant costs as they seek care underscores the need for action."

Willink is an assistant scientist at the John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

Lack of coverage translates to lack of care

Medicare provides healthcare coverage to adults age 65 and older, as well as those younger than 65 with certain diseases and disabilities. This is especially important, since half of Medicare beneficiaries live on less than $23,000 per year, according to the study authors. However, since dental care can be expensive and isn't covered by Medicare, Willink and colleagues wondered if Medicare beneficiaries were getting care.

To find out, they analyzed data from the 2012 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, which included more than 11,200 responses. The researchers then adjusted the numbers based on previous trends to estimate data for the 2016 Medicare population.

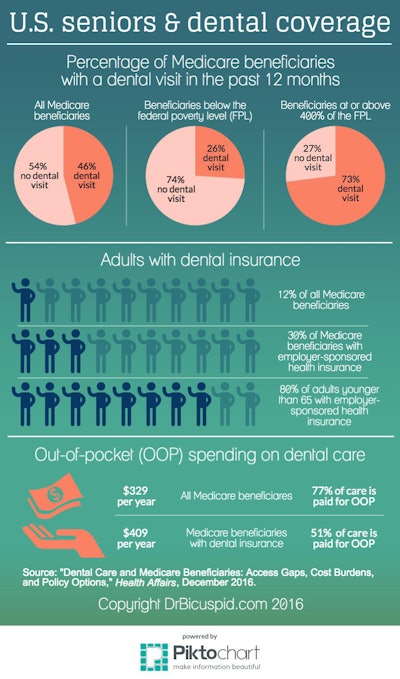

Less than half of all Medicare beneficiaries had visited the dentist in the past year, and only 12% of beneficiaries had any dental insurance at all, according to their findings. While insurance disparities decreased with higher income levels, they did not disappear.

"Medicare beneficiaries with employer-sponsored insurance were likely than those with other types of insurance to have had a dental visit and have dental coverage," the authors wrote. "However, over the past three decades, retiree coverage has become less generous -- in some cases, eliminating 'extras' that were covered, such as dental services."

Willink and colleagues also found that, on average, Medicare beneficiaries pay 77% of dental care costs out of pocket. The numbers don't get much better for those with insurance, who pay 51% of costs out of pocket. However, beneficiaries in higher income brackets, who are also more likely to have insurance, spend much more overall on dental care.

"Both total and out-of-pocket spending were more than four times as much for the highest-income group as for the lowest," the authors wrote. "Such sharp differences are unlikely to reflect the greater need for care among the wealthier group."

Fixing dental care for seniors

The study had a number of shortcomings, mostly to do with the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. Respondents self-reported their dental care use and spending, so the data may not be accurate. In addition, respondents were asked to report their total household income but only answer questions about their own dental care usage. Therefore, out-of-pocketing spending for one person may differ from other household members.

The authors emphasized their findings underscore the need to rethink dental care policies in the U.S. They outlined two ways the U.S. may be able to cover dental care for seniors, and they hope that their findings will stimulate discussion about how to improve access to care.

"Given that Medicare beneficiaries are particularly at risk for increased need for dental care as they age, addressing this deficiency in coverage would improve equity in access to dental care across the life span," Willink and colleagues concluded. "Until dental care is appropriately considered to be part of one's medical care, and financially covered as such, poor oral health will continue to be the 'silent epidemic' that impedes improving the quality of life for older adults."