DrBicuspid.com is pleased to present what will be a regular column from two lawyers who spend every day defending dentists in litigation and before the licensing board. The purpose of this column is to offer our readers a fresh perspective on common practice and risk management issues from attorneys who litigate these issues in the real world. Each article will present an actual case and leave the dentist with food for thought and practice tips to better insulate you from litigation.

A 23-year-old woman presented to the defendant general dentist with complaints of pain and swelling at tooth No. 17 on and off for several months. On clinical and radiographic examination, it was determined that the tooth was partially impacted. The patient was advised that she could have this tooth and all of her third molars extracted. Alternatively, she could wait and see if the pain progressed.

The patient opted to have all four wisdom teeth extracted. She was given the option of going to an oral surgeon where she could have IV sedation, but she declined.

The patient returned one week later for the scheduled extraction of Nos. 16 and 17. After extracting No. 16, the dentist used a mandibular block injection to numb the lower left. He then proceeded to incise a layer of tissue covering a portion of the crown of No. 17. This exposed a thin layer of eggshell-like bone over a piece of the crown, and this bone was "chipped" away with an elevator.

The dentist then used a high-speed handpiece to remove some bone on the buccal side of the tooth. He was then able to elevate the tooth out of the socket without difficulty. Sectioning was not necessary. No sutures were needed, and the procedure concluded without any complications noted. The patient was given postoperative instructions and prescriptions for Motrin and amoxicillin.

The patient telephoned the following day complaining of numbness and altered taste on the left side of her tongue. She was brought back into the office and advised that this would resolve over days or weeks, but that if did not, she would have to see an oral surgeon. At two weeks post-op with no improvement, the patient was referred to an oral surgeon who determined that the left lingual nerve had been transected. At four months postextraction, microsurgical repair of the left lingual nerve was undertaken by the oral surgeon and over the following months, only moderate improvement was reported.

Legal stance

The patient filed suit, claiming lack of informed consent and that the dentist deviated from the standard of care by causing a complete transection of the lingual nerve. The plaintiff claimed pain and suffering and loss of enjoyment of life for another 50 years. Leading into the trial, her attorneys were seeking the full $1 million policy to settle the case. The defendant refused to settle.

Issues raised

- Informed consent: The patient claimed that she was not advised of any alternatives or the risks of the extractions. The dentist testified that, although he did not have a written consent form signed by the patient, he did have discussions with her about doing nothing, the option of seeing an oral surgeon, or proceeding with him. Further, he told her that risks of the extractions included dry socket, pain, bleeding, infection, and nerve injury that could cause temporary or permanent numbness, loss of taste, and tingling.

“The patient filed suit, claiming lack of informed consent and that the dentist deviated from the standard of care by causing a complete transection of the lingual nerve.”Although the law in most states does not require consent to be obtained in writing, it would have been helpful to have a document listing these risks and signed by the patient at the time of trial. Furthermore, the dentist did not write anything in his chart documenting that he had these discussions about risks, benefits, and alternatives with the patient. That too would have been helpful in presenting our case to the jury.

Without a written consent or any documented consent discussions, the jury was going to have to decide who they believed more, the 23-year-old nursing student or the defendant. Opposing experts testified, one in support of the plaintiff's theory and one in support of the defense. - Surgical technique: At trial, plaintiff's counsel argued that the defendant deviated from the standard of care, because he failed to section the tooth and as a result, had to use excessive force to extract it. It was argued that the excessive force led to the elevator slipping and severing the lingual nerve.

Alternatively, plaintiff's counsel argued that the block injection was given too far lingually and somehow caused a complete transection of the nerve. Another argument was that the burr must have been used on the lingual side where it should not have been. Lawyers reading this will take issue with a plaintiff being permitted to present multiple theories of causation to the jury, but if you practice in New York, you know this can occur.

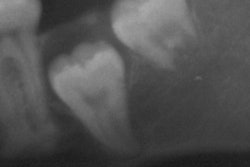

The defendant testified to textbook technique with the injection, as to the anatomical landmarks used, and his surgical technique. He explained why sectioning was not called for in this case and argued that, even with appropriate technique, there is always a risk of this type of injury occurring. - X-rays: Plaintiff's counsel argued strenuously to the jury that the dentist only took a periapical x-ray, and it failed to show the apical third of the tooth and its proximity to the inferior alveolar nerve canal. No panoramic x-ray was taken. Plaintiff's expert argued that this fell below the standard of care.

However, the expert for the defense disagreed and found the periapicals and clinical examination to be sufficient. The defense expert pointed out that the lingual nerve cannot be visualized on an x-ray, so the alleged lack of x-rays did not cause any injury in this particular case. - Failure to refer: It was argued that the general dentist was not qualified to perform this extraction and that the patient should have been referred to an oral surgeon. Plaintiff's expert testified to the additional education and training oral surgeons receive. The defense expert testified that the defendant was fully qualified based on his years in clinical practice extracting teeth like these.

Verdict: For the dentist

This case could easily have gone in favor of the plaintiff, but we believe, as is often the case at trial, that the jury members made their decision based on their emotional reaction to the parties and their experts. The jury believed that discussions covering alternatives and risks took place, so they rejected the plaintiff's testimony to the contrary.

Most important, the jury had to accept that the lingual nerve can be transected in the absence of negligence. This is not always easy to convey to a lay jury, which is why the experts were so important to the case. Both were oral surgeons, but the plaintiff's expert was caught embellishing the injuries during cross examination, and this may have caused the jury to lend less credence to his opinions.

Practice tips

- Informed consent: Have the patient sign a written consent, and make sure it adequately covers all possible risks in plain language that a patient can understand. At a minimum, discuss alternatives and risks, and note that you did so in your chart.

- Charting: Document that the patient was given referral options and declined. Make a short note of your appropriate surgical technique.

- X-rays: Take sufficient x-rays so that plaintiff's counsel will have one less avenue of attack. If possible, especially with a lower molar, take a panoramic x-ray. At a minimum, have an x-ray of the entire tooth, and for a lower extraction, be aware of the proximity of the inferior alveolar nerve canal to the apices of the roots.

William S. Spiegel, Esq., is a partner at the law firm Spiegel Leffler in New York City. He is a former assistant corporation counsel to the City of New York -- Medical Malpractice Division.

Marc R. Leffler, DDS, Esq., is also a partner at Spiegel Leffler. He received his dental degree from Columbia University, completed a residency in oral and maxillofacial surgery at New York University, and is a diplomate of the American Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery.

Disclaimer: Nothing contained in this column is intended as legal advice. Our practice is focused in the state of New York, and there are variations in rules of practice, evidence, and procedure among the states. This column scratches the surface on many legal issues that could call for a chapter unto themselves.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of DrBicuspid.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular idea, vendor, or organization.