A dry mouth and burning eyes, rampant caries, parched and irritated mucous membranes -- the life of a Sjögren's patient can be miserable. Yet many patients go undiagnosed for years, partly because dentists don't understand their role in catching and managing the syndrome, according to specialists in the disease.

Some 2.5 million Americans have the disorder, and a survey published last month found the average patient suffers for seven years before anyone figures out what's wrong.

“I would guess a high proportion of generalists miss the diagnosis.”

— Jason Tanzer, D.M.D., Ph.D.,

professor of oral medicine,

University of Connecticut

Why does it take so long? Part of the problem may be that too many dentists know too little about Sjögren's. But another part may be that experts themselves are divided on the role that general dentists should play.

"I would guess a high proportion of generalists miss the diagnosis," said Jason Tanzer, D.M.D., Ph.D., a professor of oral medicine at the University of Connecticut who has specialized in the disease. He speculated that many dentists skip ahead to treating the effects -- such as tooth decay, oral discomfort, and denture intolerance -- before identifying the underlying cause.

The problem stems partly from dental schools, said Athena Papas, D.M.D., Ph.D., a professor of dental research at Tufts University. "I think we don't -- and we're guilty of this at Tufts, too -- give [students] enough information about the disease. It's hard, if you hear about it once and then you don't hear about it for 10 years."

But overlooking the problem can have serious consequences, said Mike Brennan, D.D.S., M.H.S., director of the Sjögren's Syndrome and Salivary Disorders Center at the Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, NC. "If you don't catch it early, the patients can start to lose teeth, and it's hard for them to wear dentures."

With Sjögren's, the patient's own immune system attacks the salivary and tear glands, causing dryness of the mouth and eyes, and increasing their risk of caries. (The autoimmune rejection of salivary and tear glands may occur independently.)

Sjögren's patients also have an increased risk of B-cell lymphomas.

What to watch for

So dentists should be on the lookout for patients who complain of xerostomia. "What should go through the dentist's mind is, 'What causes dry mouth?' " Dr. Tanzer said.

Most Sjögren's patients are peri- or postmenopausal women. And contrary to popular misconception, patients mouths don't simply dry up when they get old.

But watch out: Older patients also present with xerostomia more frequently than younger ones because they're more likely to be taking medications, such as some of those for depression, incontinence, and hypertension, that can cause this symptom. So dentists should rule these out first.

General dentists should also ask if the patient has ever had radiation therapy of the head or neck since this can also cause xerostomia.

Next, they should ask about symptoms and examine for other Sjögren's-related signs, including oral mucous membrane atrophy or inflammation, reflecting usually oral yeast infections (Sjögren's patients do not typically get the white creamy lesions of thrush). They may have dry eyes, fatigue, or arthropathy. A minority of patients may also have swollen salivary glands.

Patients may also develop Sjögren's secondary to another autoimmune disease, such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, or scleroderma ("secondary Sjögren's"). The first-degree relatives of both primary and secondary Sjögren's patients tend to have these types of autoimmune disorders as well.

Sjögren's patients are also more likely than healthy individuals to get Hashimoto's thyroid disease, primary biliary cirrhosis, and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Making the call

The tricky bit comes after you suspect your patient has Sjögren's. Most experts agree that dentists treating Sjögren's patients should refer them to rheumatologists and ophthalmologists who are familiar with the syndrome, and that these specialists should also refer Sjögren's patients to dentists.

So who takes the lead?

The Sjögren's Syndrome Foundation Web site states that "Rheumatologists have primary responsibility for diagnosing and managing Sjögren's syndrome."

According to the American-European Consensus Group's Revised International Classification Criteria for Sjögren's Syndrome, a patient has primary Sjögren's if they have at least four out of six categories of signs and symptoms (see sidebar).

In theory, it's possible for a dentist to diagnose a patient under this system by asking questions about their symptoms, measuring their saliva flow, and sending them to a lab for a blood test, Dr. Brennan said.

But if some of these findings are negative, you might want to arrange screenings that are beyond the training of most dentists. In particular, you might need to perform a Schirmer's test of tear flow rate or rose bengal staining, which identifies eye damage. Both of these tests are typically done by ophthalmologists.

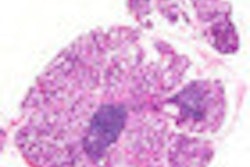

Dr. Tanzer, on the other hand, thinks dentists can make a definitive diagnosis by sending some of the patient's salivary glands to a lab for analysis. "Performance of a minor salivary gland lip biopsy is simple and quite benign," he said. "There's an easy procedure for plucking out five to 10 tiny glands after making a tiny incision in the inner surface of the lip under local anesthesia. It's less invasive than a filling or scaling and root planing."

Dr. Tanzer said he had never seen a patient with either resulting numbness or other persistent discomfort. "I don't even place sutures in the small wound," he said. "Rather, I just have the patient thrust their tongue into the cut area to stop the minor bleeding."

Dr. Papas disagreed. "I'm not sure the dental office is the place for lip biopsy," she said, noting that 6% to 8% of patients may end up with lip numbness after a biopsy.

"It's not uncommon to get pain and bruising," added Dr. Brennan, though he said permanent nerve damage is rare.

The bottom line? Dentists who want to add lip biopsy to their repertoire should get good training in the procedure. Otherwise, it's a good idea to refer to an oral surgeon or Sjögren's specialist.

"Whoever does the procedure, there seems to be no justification for cutting a wedge out of the lip of a suspected Sjögren's patient," which is how the biopsy has sometimes been done, Dr. Tanzer said.

Helping the patient

After the diagnosis is made, dentists play a key role in alleviating some of the most common problems. "The big, expensive thing in Sjögren's is aggressive tooth decay," Dr. Tanzer said. "Without salivary buffering and cleaning of the oral cavity, there tends to be uncontrolled colonization of the surfaces of the teeth."

The answer isn't to start by filling the cavities; in Sjögren's, decay is particularly common around the margins of restorations. "If you start drilling holes in teeth, you're just going to make more filling margins available," he said.

Barring a toothache or some other emergency, Dr. Tanzer recommends beginning with prescribing and maintaining intensive topical fluoride applications to the teeth, using any of the various neutral gels on the market that are usable at home.

He also warns against sweets between meals. That's particularly important for these patients because many suck candy to compensate for the dryness they are feeling -- sometimes on the misguided advice of a physician. "I can't tell you how many patients have had their physicians say, 'Oh, Mary, just suck on a lemon drop.' " Coffee with sugar is another common problem, Dr. Tanzer said.

Though no controlled studies of sugar substitutes have been conducted specifically for Sjögren's patients, research on caries in general suggests that hard candy with sorbitol or -- better yet -- xylitol (high content) should be recommended. Xylitol gum is likely to have benefits, but the xerostomia makes chewing gum difficult for some patients.

Yeast infections of the oral mucosa are common and should be aggressively treated as well, but not with antiyeast medications that contain sugars unless the patient is maintained on intensive topical fluoride or no longer has any teeth.

Because of mucous membrane inflammation, rinses containing alcohol may be painful for these patients. Most of Dr. Tanzer's Sjögren's patients have refused to use chlorhexidine rinse, probably for this reason. (Dr. Tanzer also suspects that the chlorhexidine concentration isn't high enough as sold in the U.S. to have a strong effect.) Antiyeast antibiotics are available in the form of troches (lozenges), but they have to be used after dentures are removed and disinfected, and the lips should also be treated with an antiyeast topical ointment.

Some patients get relief from using oral lubricants (also known as artificial saliva); Dr. Tanzer has prescribed a variety of them with equally good palliative results. "They give about 20 or 30 minutes of lubrication," he said. "I recommend the ones without lemon flavor, because citric acid can contribute to erosion, which can be an added problem for Sjögren's patients."

Dr. Papas also tries to remineralize her patients' teeth using Caphosol and MI Paste, both of which contain calcium phosphate. (Dr. Papas is in the Caphosol speaker's bureau.)

Dentists can also prescribe a couple of systemic medications, pilocarpine hydrochloride (Salagen) and cevimeline (Evoxac). Both belong to the class of cholinergic medications that stimulate moisture-producing glands throughout the body.

But success in stimulating a patient's salivary secretion depends on how much function remains in them. And these drugs can, if overused, cause troublesome side effects, including sweatiness, headaches, frequent urination, nausea, and cardiovascular effects.

A number of other compounds are being tested as Sjögren's drugs.

In the meantime, dentists can make all the difference.