Our mouths are home to billions of microbes, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms. These tiny tenants, collectively called the oral microbiota, are vital to our oral health, which depends on a delicate balance between harmful and helpful microbes.

Disruption of this balance can lead to inflammation-related oral infections, such as periodontal disease, which can cause loss of alveolar bone that supports and anchors the teeth. But the microbes in our mouths may not be the only ones to blame for alveolar bone loss.

It turns out, specific bacteria in the gut also appear to play a role in maintaining alveolar bone, according to a recent study supported by the U.S. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) and published in Laboratory Investigation (December 21, 2021, Vol. 102, pp. 363-375).

The findings show that bacteria in the gut kick immune cells into gear, which in turn release a series of molecules that prompt alveolar bone loss. The study challenges previous notions that bone loss in the mouth is regulated solely by oral microbes. It also opens the possibility that noninvasive interventions to modulate gut bacteria, such as changing one's diet or taking probiotics, could support oral health.

"It's well known that shifts in the oral microbiota can induce inflammatory immune responses that cause bone destruction," says Dr. Chad Novince, PhD, the study's senior author and associate professor at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). "But nobody had asked the question, 'Could commensal gut microbes also have an impact on the health of alveolar bone?'"

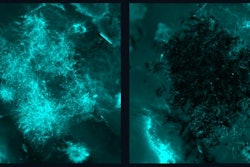

To find out, the team narrowed in on one type of gut microbe called segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB). The threadlike bacteria are often found clinging to the intestinal walls of animals and humans, but not the mouth.

The researchers planted SFB into the guts of young mice that had been raised germ-free -- meaning their bodies contained no microorganisms -- to pinpoint its effects. After six weeks, the germ-free mice implanted with SFB had overactivated immune cells, larger-sized bone-degrading cells in alveolar bone marrow, and loss of bone surrounding the teeth.

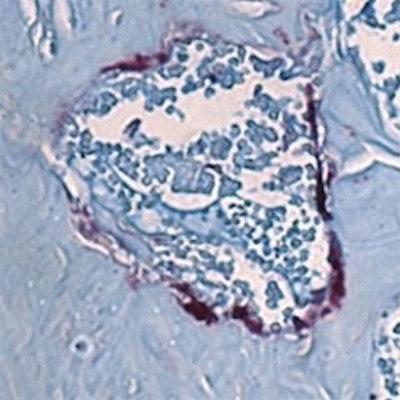

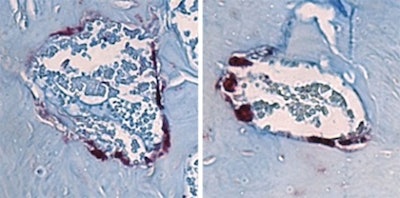

Bone-degrading cells (maroon) in the jawbone marrow of mice. The cells are smaller in the mice lacking all microbes (left) than those in mice with the SFB gut microbe associated with jawbone loss (right). Image courtesy of Novince Lab.

Bone-degrading cells (maroon) in the jawbone marrow of mice. The cells are smaller in the mice lacking all microbes (left) than those in mice with the SFB gut microbe associated with jawbone loss (right). Image courtesy of Novince Lab.Together, bone-degrading osteoclasts and bone-generating osteoblasts carefully balance skeletal health. Shifts in their activity or miscommunication between them can tilt the scale toward the type of bone loss that the MUSC researchers saw in mice.

Further experiments showed how this happens: SFB appeared to trigger the release of a high quantity of immune molecules in the gut that enter the body's circulation, ultimately setting off an immune response in bone marrow, including alveolar bone marrow. The researchers found that this resulted in the release of an immune molecule called tumor necrosis factor, which disrupts the regular communication between bone-generating and bone-degrading cells in alveolar bone marrow, ultimately leading to bone loss.

Chad Novince (left), Jessica Hathaway-Schrader (right), and colleagues reported that certain bacteria in the gut can contribute to bone loss associated with periodontal disease. Image courtesy of MUSC.

Chad Novince (left), Jessica Hathaway-Schrader (right), and colleagues reported that certain bacteria in the gut can contribute to bone loss associated with periodontal disease. Image courtesy of MUSC."It's a fascinating discovery to me," says Novince. "Our study is one of the first that is beginning to define the mechanisms of how the gut microbiota can modulate aspects of systemic immunity and, ultimately, distant skeletal sites, including the alveolar bone, or jawbone."

Novince and the team plan to determine how other microbial populations from various body sites might drive changes in alveolar bone. They hope to gain a better understanding of how microbes, the immune system, and the skeletal system interact to shift the balance between health and disease.

The current study's findings may help explain why some patients with inflammatory bowel conditions, such as Crohn's disease and irritable bowel syndrome, where organisms like SFB flourish, develop periodontal disease-related bone loss. The results add to evidence from previous studies that suggest probiotics could be used to fine-tune the composition of gut microbes to help prevent alveolar bone loss from severe gum disease.

"We're not able to say there's a cause and effect, but it supports the idea of a correlation between periodontal health and inflammatory bowel conditions," says first author Jessica Hathaway-Schrader, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at MUSC. "It implies that the gut microbiome does play a role in providing health and homeostasis for the oral cavity."

Reprinted from the U.S. National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of DrBicuspid.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular idea, vendor, or organization.